Mitzi Oka McCullough looks at an exhibit displaying birds carved by her father during the time their family was held in an internment camp for Japanese Americans during World War II. (Photo by Anthony Marroquin/Cronkite News)

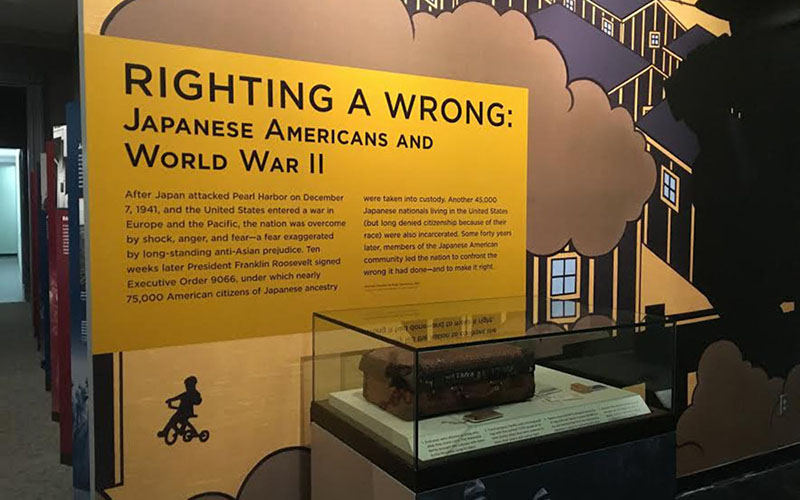

The entrance to the new exhibit of the new exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.on the U.S. use of internment camps for Japanese Americans during World War II. (Photo by Kendra Penningroth/Cronkite News)

A case shows internment camp artifacts in “Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II.” The exhibit opened on the 75th anniversary of the order creating the camps. (Photo by Kendra Penningroth/Cronkite News)

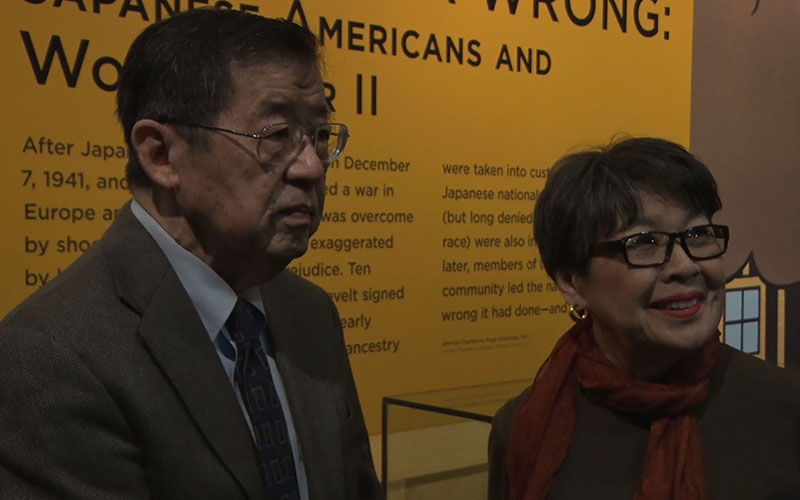

Seishi Oka and his sister, Mitzi Oka McCullough, were 5 and 3 when their family was put in an internment camp in Arizona for Japanese Americans during World War II. (Photo by Anthony Marroquin/Cronkite News)

A display of the wooden birds carved by Sadao Oka, the father of Seishi and Mitzi, while the family was held in the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona during World War II. (Photo by Kendra Penningroth/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – Seishi Oka was 5 and his sister, Mitzi, only 3, when their family was loaded on to a train and taken from their Salinas, California, home to the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona.

Oka said he only vividly remembers two things about the train ride: Hearing a coyote howl for the first time, and wondering to himself, “Why do they hate us so much?”

“They” were the soldiers who rounded up the Okas and thousands of other Japanese-Americans and shipped them off to internment camps during World War II, something the young Seishi could not fully understand.

“On the train … it was that fear and loneliness,” Oka said Friday. “It was really dark, and very strange.”

He was in Washington with his sister Friday for the opening of a new exhibit, “Righting a Wrong: Japanese-Americans and World War II,” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

The exhibit marks the 75th anniversary Sunday of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066. Signed just months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the order led to the internment of 75,000 Japanese Americans, and kept 45,000 Japanese immigrants from becoming naturalized citizens.

“Righting a wrong, I don’t know if a wrong can actually really be righted,” Oka said, looking at the sign for the exhibit. “But we can learn from that wrong.”

Curator and project director Jennifer Jones hopes that is the case. She said the exhibit is an opportunity for visitors to understand what happened 75 years ago and use that knowledge to understand the present.

“This exhibition really explores a period in American history when war and fear and racial prejudice overtook the nation, and through executive action, determined the fate of almost 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry,” she said.

Jones said the museum been collecting artifacts from Japanese-Americans since 1987 and now has “a few thousand” items, only a fraction of which are on display.

-Cronkite News video by Anthony Marroquin

Among those artifacts is a collection of wooden birds, carved and painted by the Okas’ father.

Mitzi – now Mitzi Oka McCullough – said her parents were paid $16 a month, but her father would spend whatever money he had to to create the birds. McCullough’s older sister told her their father was very resourceful, using screens found in the barracks and old fruit boxes to bring the birds to life.

McCullough describes her 3-year-old self as “momma-oriented,” and just thankful to be with her family during that time. For the most part, she remembers the rosy aspects of childhood: Playing in the hot sun and eating Eskimo Pie ice cream.

“It was such a highlight for a little kid … a lot of little incidents like that I remember,” McCullough said.

While her memories of the family’s time in Poston are filtered through a child’s eyes, she said her older siblings and parents remembered things very differently.

Oka remembers attending a camp school built by fellow internees. He was not sure where his teachers came from, but he describes them as being “indifferent” to the children’s situation.

McCullough said she wishes she had pressured her parents to speak more about their experiences while they were still alive. She said she will not dare ask her eldest brother to speak about it: She thinks he was forced to grow up quickly and take on a lot of responsibilities, and as a result “clams up” whenever asked about his time there.

Her older sister has taken it upon herself to share the Okas’ story, McCullough said, with both the world and her younger siblings. It was that sister who donated the birds to the Smithsonian.

Jones said that many of the families that donate come back to see their artifacts, and are “very proud” of their contributions and grateful that their history is important to people.

Oka is glad that the stories of those affected by the Japanese internment are being told and he hopes that given the current political climate, Americans have learned something from the past.

“If we forget what was done, we may, we being America, may try something again,” Oka said. “Having that happen again would be pretty difficult, but if there are identifiable groups that are small enough, they (Americans) may forget what they did to the Japanese.”