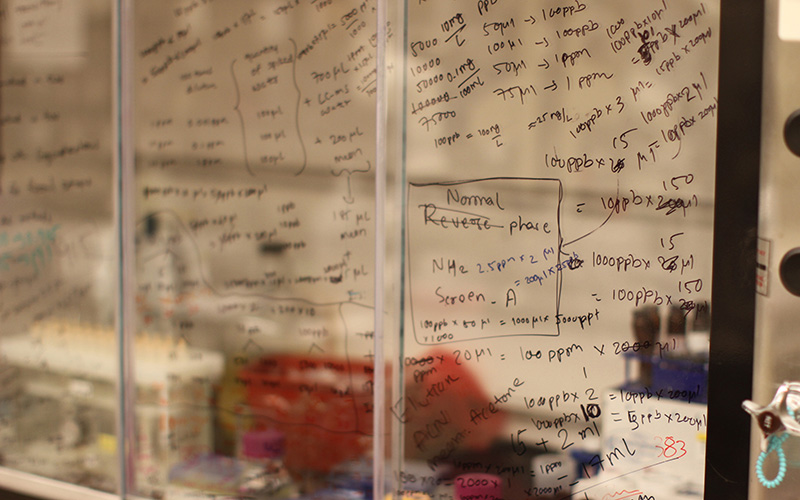

TEMPE – Pristine white lab coats hang on a wheeled rack. Handwritten measurements and equations are crammed on whiteboards. And a long line of freezers are filled with containers of super-concentrated human waste.

That’s right. At the Tempe lab of scientist Rolf Halden, researchers study samples of sewage sludge from wastewater treatment plants across the U.S. to identify health threats. Sludge also uncovers clues about unsafe chemicals that stick around in the human body and to emerging behavioral trends in communities, like alcohol and prescription-drug use.

“We use wastewater treatment plants as observatories where we can understand the chemistry and the biology of the people,” said Halden, director of the Center for Environmental Security at ASU’s Biodesign Institute.

Human waste gives unique insight into a person’s health, which is why doctors often request urine or stool samples from their patients. Sewage sludge is equally insightful, but on a larger scale.

“We essentially take the tools that the medical doctor already uses in his or her practice for diagnosing people, and we apply those tools to cities,” Halden said. “Rather than diagnosing an individual, we are the doctors diagnosing the whole city and its population.”

From alcohol to antimicrobials, from viruses to prescription drugs: to identify each possible health threat, Halden and his researchers look to the stuff we flush down toilets.

“It can get kind of gross”

Sewage sludge is a highly concentrated byproduct of the wastewater treatment process. In Mesa, the Northwest Water Reclamation Plant is one of many wastewater treatment plants to provide sludge samples to Halden’s lab.

Plant operator Brian Innis said the Mesa plant processes an average of 8 1/2-million gallons of wastewater daily, making it a medium-sized plant.

Plant operator Brian Innis stands inside an aeration basin at a wastewater treatment plan in Mesa. (Photo by Cassie Ronda/Cronkite News)

“We try to engineer a process that does what a river could do for sewage over miles,” Innis said, “and we try to condense that process down to something that could be done in 20 or 40 acres of land.”

The process starts where raw sewage enters the plant in a constant, smelly stream throughout the day. Various items flow in with the wastewater, and Innis warned “it can get kind of gross.” One material in particular often tangles with the plant’s sophisticated machinery.

“Most of those wipes that you buy at the store that say they’re flushable? We’d really prefer people not to flush them,” Innis said, laughing.

After the wastewater enters the plant, it is separated into liquids and solids, with each part taking a different path. Much of the dirty work takes place inside carefully calibrated industrial machinery, but human operators use computers and simple lab equipment to monitor every step.

Operators at the Mesa wastewater-treatment plant use computerized systems to keep the plant running smoothly, but they also use old-fashioned, hands-on work in many parts of the process. (Photo by Cassie Ronda/Cronkite News)

The liquids go to bubbling cauldrons called “aeration basins,” where oxygen-loving microorganisms live to eat up disease-carrying bacteria. After the microorganisms are removed, the liquid rushes through layers of a giant cloth filter, becoming gradually clearer. Then it gets zapped by ultraviolet light to kill or inactivate any leftover bacteria. Lastly, the substantially purified water trickles through a soil column and is stored in underground reserves in case of drought.

The solids are settled out, spun at high speeds, thickened, heated and finally fermented in the plant’s “digesters,” two golf-ball-shaped towers which are visible from Loop 202 and Dobson exit. Each digester contains about 750,000 gallons of sludge, Innis said. The final product can be trucked out to fertilize animal feed crops or sent in samples to research labs like Halden’s.

The Northwest Water Reclamation Plant in Mesa processes an average of 8 1/2 million gallons of wastewater daily. (Photo by Cassie Ronda/Cronkite News)

“The sewage sludge can’t lie”

Even after all the steps, certain substances in the sewage sludge never fully disappear. That includes prescription drugs, toxic chemicals and antimicrobials.

“It turns out that the bad chemicals that accumulate in sewage sludge are the same chemicals that are accumulating in our body, in our adipose and fat tissue,” Halden said.

Rolf Halden, director for the Center of Environmental Security at the Biodesign Institute, in his office at Arizona State University in Tempe. (Photo by Cassie Ronda/Cronkite News)

By looking at what remains in the sludge, researchers can find out which substances tend to stick around in the human body. In one significant example, Halden and his team at Johns Hopkins University used sludge analysis in 2004 to show that certain antimicrobials persist for years in U.S. water resources, which correlates with a rise in harmful antibiotic-resistance genes. The research ultimately led to the recent FDA ban on antimicrobial soaps.

Sewage sludge can also reveal behavioral trends in cities. Compared to health questionnaires, which rely on people to give truthful answers, the sludge is significantly more reliable.

“Oftentimes people don’t give you an honest answer to the questions you pose, particularly when it enters into your kind of private life: consumption of alcohol and drugs and so forth,” Halden said.

Doctorate student Joshua Steele, who works in Halden’s lab, put it best.

“The sewage sludge can’t lie.”

Keeping cities’ secrets

Halden’s lab is a veritable chamber of secrets, like which U.S. cities have particularly high concentrations of prescription painkillers in the wastewater. But Halden keeps the findings close. The lab maintains confidentiality agreements with cities, since some of the information could create bad press, which Halden called “not helpful.” Instead, the data is provided directly to local health officials.

“We have some communities where we do monthly monitoring and provide them with monthly data on how they’re doing,” Halden said. The information can be especially helpful for cities trying to implement new health policies or education campaigns.

In his lab, Rolf Halden, director for the Center of Environmental Security, and his assistants seek to identify chemical, biological and behavioral threats in sewage sludge. (Photo by Cassie Ronda/Cronkite News)

“They can see in real time whether the efforts they make, whether they are paying off with respect to reduction in the consumption of these drugs,” he said.

By providing real-time feedback, wastewater analysis shows which health interventions work, Halden said.

“Hopefully we can bring (these interventions) to different cities, different communities, and help improve health across the United States and ultimately around the world.”