Yavapai pitching coach Jerry Dawson doesn’t think it’s a good idea for baseball players to play the game year-round. (Photo by Lindsey Wisniewski/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX — “Year-round baseball is one thing that’s killing our sport,” Horizon High School head coach Eric Kibler said.

“It’s a big fatigue factor,” said Kibler, who has led the Huskies’ program since 1981. “When you get fatigued, you get injured.”

In Arizona, where the weather is almost always great, baseball is a year-round sport. However, there is growing evidence that year-round baseball is causing both physical and mental strain on young players.

Yavapai College pitching coach Jerry Dawson, who began his coaching career in 1972 at Chaparral High School, said that players who decide to play the game all year could be taking a big risk.

“You can go 12 months a year if you chose to do it,” Dawson said. “I don’t think it’s wise. I don’t think it’s smart. I think overuse is becoming a major red flag in our sport.”

Pitching problems

Both coaches said pitchers are most at risk. Kibler even mentioned that major league teams may factor this constant play into their draft evaluations.

“When they look at pitchers, sometimes they look at a kid that rests,” Kibler said.

It’s that rest that might lead a team to believe that one player is less of an injury risk than another who plays all year. The American Sports Medicine Institute found that pitchers were five times as likely to suffer an injury requiring surgery if they competed for more than eight months per year. One of the surgeries that has seen a rise in performance on youth players is Tommy John surgery.

Tommy John surgery is a procedure used to treat a tear to the ulnar collateral ligament in the elbow. It is caused by repetitive use, in this case the continual throwing of a baseball. The surgery replaces the torn ligament with a tendon from somewhere else in the person’s body.

Tommy John surgery was first performed in 1974 by Dr. Frank Jobe on Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Tommy John. John went into the surgery with 124 wins and one All-Star selection. After surgery, he played 14 seasons with 164 wins and three All-Star selections.

Dawson didn’t think Tommy John surgery would ever be something performed on pitchers who had not yet received their high school diploma.

“I never heard of a Tommy John surgery for a high school kid when I was starting out in the 1970s,” Dawson said.

But now at Yavapai, Dawson runs into this problem more each year.

“We had two young people in our program this year that had already had Tommy John surgery in high school,” Dawson said.

According to the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, more than half of the Tommy John surgeries in the U.S. between 2007 and 2011 were performed on patients between the ages of 15 and 19.

When young pitchers look at major leaguers like the Washington Nationals Stephen Strasburg and the St. Louis Cardinals Adam Wainwright, both of whom have made successful returns from Tommy John surgery, there may be an impression that anyone who gets the surgery will come back better. Dawson tried to dispel that notion.

“Any time you have a surgery…you’re never the same,” Dawson said.

Arizona Diamondbacks pitcher Jake Barrett, who hasn’t gone through the surgery himself, said that he played as much baseball as he could growing up and the thought of injury never stopped him.

“I was one of those guys that just played year round,” Barrett said. “When I was young, I always wanted to play so that never bothered me.”

Getting guidelines

The National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) has attempted to combat this issue with a new rule saying that member states must come up with a required pitching limit by the start of the 2017 season in an effort to give pitchers a chance to rest and curb the overuse. All 50 states plus the District of Columbia are NFHS members, so this rule will take effect nationwide.

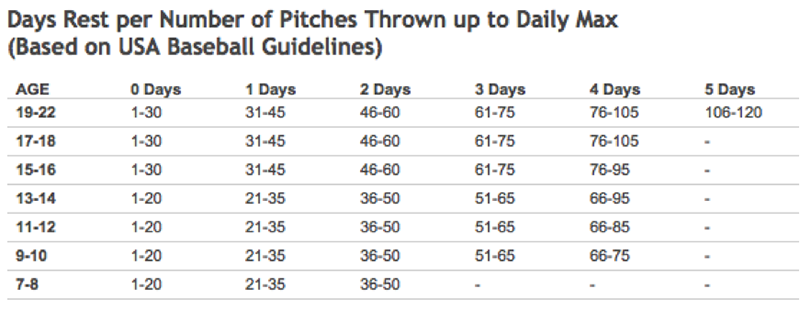

Arizona’s member association, the Arizona Interscholastic Association, will be turning to pitch count guidelines put together by USA Baseball as part of their Pitch Smart campaign, according to David Hines, assistant executive director of the AIA.

“There is a chart and it is by age,” Hines said. “That is what we are going to use.”

The Pitch Smart program is a joint initiative by USA Baseball and Major League Baseball that works to educate people about this issue and give helpful guides to youth leagues.

“The issue of overuse injuries in amateur baseball is acute, often stemming from a lack of basic standards and education,” said Rick Riccobono, Chief Development Officer at USA Baseball. “The program aims to provide practical, age appropriate guidelines for coaches, players and parents to help ensure healthy playing careers.”

Hines was hopeful that the rule would make a difference, especially since there didn’t seem to be any resistance to it.

“The majority of our coaches are in favor of the rule,” Hines said. “And really the majority of our longer, well-established coaches already follow their own pitch count.”

Hines said that the new rule would help with the main goal of the AIA.

“The priority is we’re looking out for the safety of our kids,” Hines said.

Shattered spirits

It’s not only players’ bodies that can get worn from year-round baseball. Kibler has also seen kids spirits and love of the game slowly erode under the never-ending schedule of games.

“I just see kids get burned out,” Kibler said.

The National Alliance for Youth Sports reported in a poll that 70 percent of kids quit organized sports by the age of 13.

“Something’s happening in that time where they’re just tired,” Kibler said. “Look how many games you played for five, six years and then come up to high school, you just won’t play anymore.”

Former Scottsdale Community College baseball player Marcus Still played baseball, football and ran track at Queen Creek High School. He said that playing different sports allowed him to channel different emotions into each, and would help him enjoy baseball even more.

“I have a football mindset, where I wanna go out and hit someone or go out and be hyped up,” Still said. “But when I get to baseball, when I get on the field, it’s like peace. I’m at peace when I’m out here.”

Kibler said diversifying what baseball players do during the year or just giving more time over to practicing than playing games could be solutions to the overuse problem.

“I think balancing their life out, playing another sport, having time when you rest,” Kibler said. “You have a time when you’re training, training for the sport instead of just playing all the time.”

It’s practice and training that Kibler says drives most of the development in young baseball players.

“You’re not gonna get a lot better playing all the time,” Kibler said. “Just playing is not going to develop you as much as some training.”

Kibler said there needs to be some kind of adjustment made in youth sports to stop these two growing trends.

“The culture needs to change, that especially younger, when you’re 8U, 9U,” Kibler said, referring to 8-and-under and 9-and-under baseball leagues. “Do you really have to play year-round, travel all over the place?”

With the conditions that Arizona provides though, Dawson said this problem might not be going away any time soon.

“The weather is there and the opportunities are there,” said Dawson.

Cronkite News reporters Trisha Garcia and Lindsey Wisniewski contributed to this report.

Pitchers share Tommy John stories to guide each other through rehab

Pitchers share Tommy John stories to guide each other through rehab