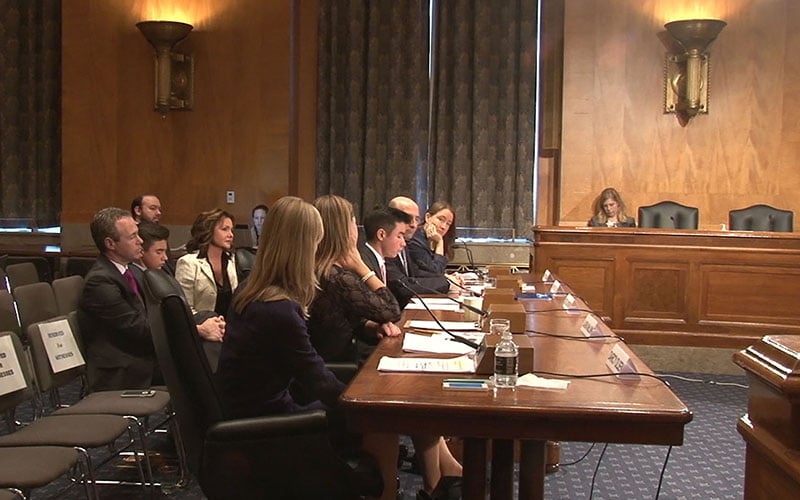

From left, Jason, Mateo and Paulina Morris listen as son and brother, Diego, testifies to a Senate panel on making experimental drugs available to critically ill children. The Morrises moved to London for treatment that was unavailable in the U.S. for Diego’s cancer. (Photo by Wafa Shahid/Cronkite News)

Diego Morris, 15, of Phoenix, testifying to the Senate Homeland Security Committee with other supporters of right-to-try initiatives that would give terminally ill children access to drugs not approved in the U.S. but available in other countries. (Photo by Wafa Shahid/Cronkite News)

Diego Morris told a Senate panel that he and his family were not looking for guarantees when they want overseas to get medical help he could not et in the U.S. – just hope. Four years after his treatment, the Phoenix 15-year-old is cancer-free. (Photo by Wafa Shahid/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – When his family moved from Phoenix to London so he could get treatment for a potentially deadly form of cancer, Brophy College Preparatory student Diego Morris said they were “not looking for guarantees – just hope.”

Hope that other children might not have because they cannot travel overseas for experimental treatments that are not available in the U.S.

“I think it’s important that people should not have to go through the same situation we had,” Diego said after testifying Thursday to a Senate committee considering whether potentially life-saving drugs should be made available to U.S. children with terminal diseases.

The 15-year-old Diego, backed by his parents, joined a panel of advocates and doctors pressing the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs for action.

Editor’s note:

A previous version of this story misidentified Morris family members in a photo caption. They were Diego Morris’ parents, Jason and Paulina, and his brother, Mateo. The caption has been corrected.

Darcy Olsen, the president and CEO of the Goldwater Institute, told the committee that she is tired of seeing new drugs become “caught up in the FDA’s (Food and Drug Administration) pipeline.”

“We have the right to die when we’re terminally ill, fantastic. But what about those who want to fight?” Olsen testified.

The institute is advocating for right-to-try and compassionate use measures across the U.S. by sharing stories of people like Diego, who is an honorary chairman of its right-to-try campaign. Goldwater is also pushing states to pass measures that would decrease time and paperwork for patients seeking innovative treatments.

Dr. Joseph Gulfo testified that the process by which the FDA tests and approves drugs oversteps its mandate of making sure drugs are “safe and effective.” By doing so, he said, the FDA “stifles medical innovation.”

“Benefit-risk is a private health decision to be made by doctors and patients when weighing whether to use drugs that are safe and effective,” said Gulfo, who runs the Rothman Institute of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Fairleigh Dickinson University.

Nancy Goodman, who founded the pediatric cancer research group Kids v. Cancer after her son, Jacob, died of brain cancer, echoed Gulfo’s comments.

“The drugs given to my son were 40 years old,” Goodman testified. “There needs to be a broader approach to this problem.”

She urged the committee to “incentivize companies to create drugs for pediatric cancer” and give children access to drugs that are available to adults.

Diego said he also wants “to see the process expedited.”

His own journey began four years ago, when an 11-year-old Diego woke up one morning with pain in one of his knees that he attributed to time spent playing soccer and baseball. But the pain persisted, and doctors soon confirmed that he had osteosarcoma, a rare, but aggressive form of bone cancer.

“Everything just started happening quickly after that,” said Diego, who went through 21 rounds of exhaustive chemotherapy treatments.

When those didn’t cure the disease, the Morrises began to ask doctors for newer treatments, eventually learning about a drug called Mifamurtide. It was being used in Europe to treat osteosarcoma, but had not won FDA approval for use in the U.S.

So the Morrises packed up and moved to London to try the treatment, which eventually sent his cancer into remission.

Diego told the committee that he is now cancer-free. He considers himself lucky to be healthy, and lucky that his family had “the resources to move for treatment,” acknowledging that “most families do not have those resources.”

He called on lawmakers and federal agencies should “give families and patients the opportunity to save their own lives, and give hope to patients and families when they have no hope.”

– Cronkite News reporter Wafa Shahid contributed to this story.