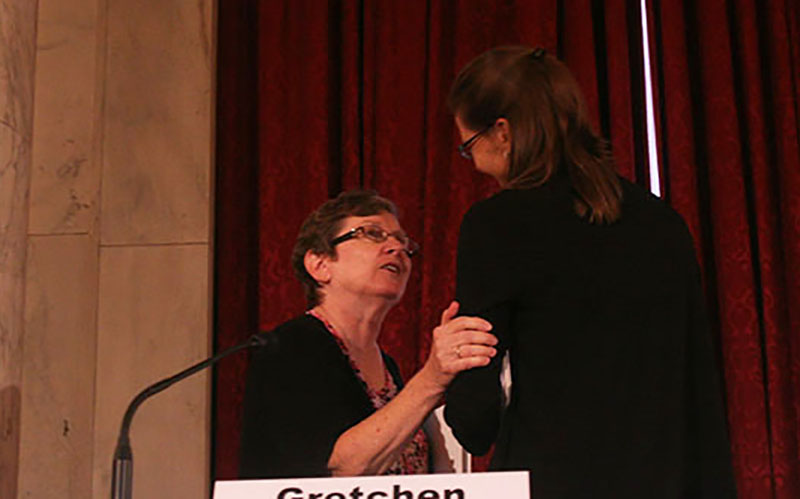

Sister Adele O’Sullivan speaks with Gretchen Hammer, Medicaid director of Colorado’s Department of Health Care Policy and Financing, after a briefing in Washington. (Photo by Soyenixe Lopez)

WASHINGTON – Sister Adele O’Sullivan said he was known as Mr. 280, a homeless man with chronic mental illness whose trips in and out of the hospital racked up bills of more than $358,000 over several years.

But now, with supportive housing and a part-time job, his health issues are being treated, said O’Sullivan, founder of Circle the City, a Phoenix charity that helps care for homeless people after they have been released from the hospital.

She was part of a panel organized by the Alliance for Health Reform that met in Washington Friday to discuss the relationship between health and housing.

“Homelessness causes poor health,” said Barbara Dipietro, director of policy and advocacy for the National Health Care for the Homeless Council, one of the panelists.

“Living in the streets and in shelters is stressful and if you didn’t have issues before, you tend to develop them when you are homeless,” Diprieto said.

A perfect example of that was Mr. 280, so-called because he logged 280 hospital visits between 2007 and 2013. He was well-known to firefighters for his frequent calls to 911 asking to be taken to the hospital, O’Sullivan said.

It was after he spent several weeks at Circle the City in 2013 that Mr. 280, who suffers from a brain injury, was able to get proper medical care, get permanent housing and a part-time job at a local restaurant. O’Sullivan said he has been to the hospital only two times since.

Most of the panelists Friday agreed that affordable housing is essential to the health of individuals who are homeless and suffer from chronic illnesses and that Medicaid funding for supported housing units is key.

Jennifer Ho, senior adviser for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, agreed that the health care system has a huge stake in creating more integrated housing options for individuals with disabilities. Part of that is to make housing more affordable and accessible, said Ho, one of four panelists at the Friday briefing.

“As we grow older we are more likely to live alone, have more chronic health conditions, less mobility, and we grow up poorer,” Ho said.

But that would require funding and investment from the federal government, which she said is not something that’s being talked about in Congress.

“When we ask Congress to invest in more affordable or supportive housing, they worry about renewal burden,” Ho said.

“HUD pays for a lot of services and housing that Medicaid could pay for … but Medicaid is already under a lot of political pressure,” she said.

O’Sullivan said progress is being made, but more needs to be done.

“Arizona decreased chronic homelessness by 15 percent between 2013 and 2014 … and the number of supporting housing units is growing,” she said. “Medicaid has helped fund 1,600 supportive units in Maricopa County but we still need about 1,000 more units to end chronic homelessness.”

O’Sullivan said coordination and prioritizing the supports in terms of medical needs for the homeless are key to keeping medically vulnerable people from dying in the streets.

“Medicaid is wonderful but Medicaid alone can’t do it,” O’Sullivan said. “We need the support of our mental health providers, we need HUD and we need housing.”