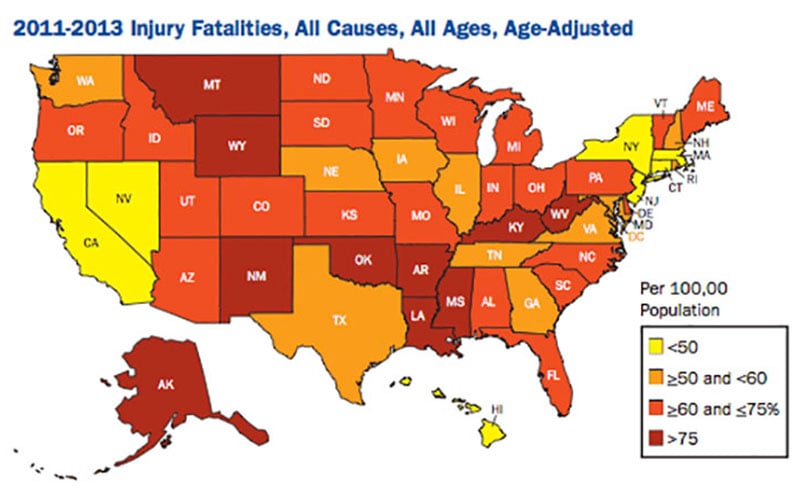

WASHINGTON – Arizona had the nation’s 12th-highest rate of deaths from injuries from 2011 to 2013, and drug-related injuries accounted for the largest number of those deaths, a new report says.

Deadly injuries

The rate of different types of injury-caused deaths in Arizona from 2011 to 2013, per 100,000 residents:

The report by the Trust for America’s Health said Arizona had a rate of 73.4 deaths per 100,000 people caused by injuries – everything from accidents to shootings to suicides – well over the national rate of 58.4 injury-caused deaths per 100,000 people in the period.

The state’s rate was also worse than the 70.7 per 100,000 it recorded in the last such report, for 2007-2009, when Arizona ranked 15th-highest.

“Injuries are not just acts of fate,” said Jeffrey Levi, executive director of the Trust for America’s Health, as he released the report Wednesday. “Research shows they are pretty predictable and preventable.”

“The Facts Hurt: A State-by State Injury Prevention Policy Report” said injury remained the leading cause of death for Americans ages 1 to 44.

But it said that drugs have risen to become the leading cause of injury in 36 states, including Arizona, outstripping even motor vehicle injuries.

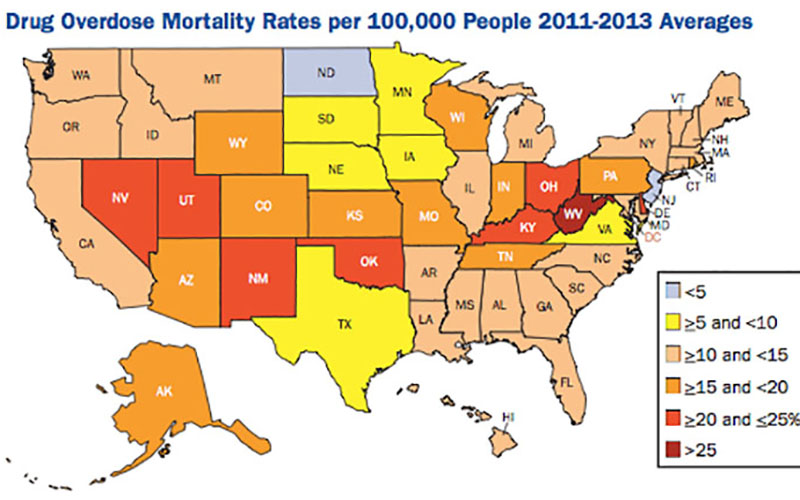

The report said Arizona’s drug overdose death rate of 17.8 fatalities per 100,000 people was 10th-highest in the nation.

Nationally, half of the 44,000 annual drug overdose deaths came from prescription drugs.

Prevention prescription

How Arizona fared on a national report card on injury-prevention measures.

Arizona got credit for having:

Arizona failed for not having:

“Prescription drug abuse is a national epidemic,” Levi said.

The report also graded each state’s injury prevention efforts, with Arizona getting points for four of the 10 indicators measured. It was in good company: 29 states got scores of 5 or less.

Arizona got points for its prescription drug monitoring program, which requires that health care providers monitor prescription drugs for instances of overprescribing or doctor-shopping. It also requires that patients disclose their prescription information to all their doctors.

The state was knocked, however, for its lack of a “rescue drug” law. Such laws allow the administration of naloxone, a drug that can be used to counteract overdoses, by lay people as well as medical professionals.

Sharon Stancliff, the medical director for Harm Reduction Coalition, said rescue drug laws almost always pass once they are introduced in the state legislature and she was not sure why Arizona had not done so.

State health officials and experts with universities and private groups in Arizona did not immediately return calls seeking comment on the report Wednesday.

But Stancliff said a prescription drug monitoring program alone is not enough to help with every stage of addiction.

“I think you need a lot of different things,” she said. Prescription monitoring plans can help keep people from getting addicted, but those are are already dependent also need help, she said.

In addition to reducing people from getting addicted in the first place, she said, health care officials need access to addiction-breaking drugs to wean people off their addictions as well as access to drugs like naloxone stop overdoses in a crisis.

There are no specific reasons why states have not adopted all the measures recommended in the report, said Albert Lang, a Trust for America’s Health spokesman. But he said the trust looks at numbers on the state level because “it’s a lot more useful” to scale the data down from national numbers.

Besides getting “more information out,” the state breakout lets lawmakers and other officials see specific improvements and weak spots in their states, he said.

“It’s not rocket science,” Levi said of actions needed to be taken to reduce deaths from injury. “But it does require some commonsense and investment in good public health practice.”