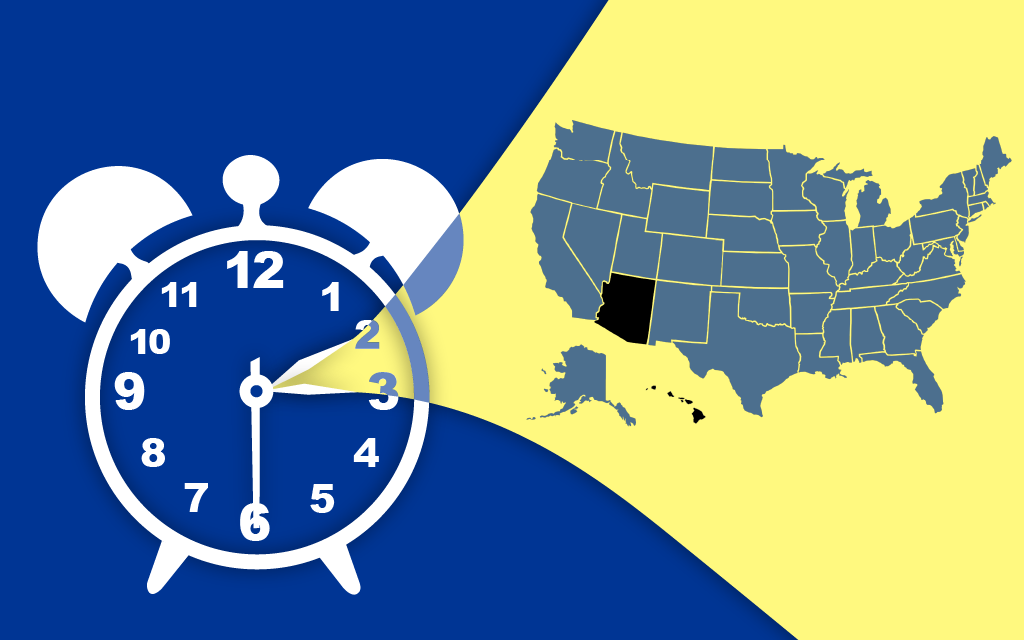

WASHINGTON – A national consensus has emerged over the last 25 years that it’s time to stop changing the clock twice a year. Every spring and fall, Arizonans look on with relief and satisfaction, enjoying their exemption from that ritual.

A Gallup poll conducted in January found that more than half of U.S. adults favor an end to the biannual ritual. The Senate unanimously approved a bill in 2022 to end the practice.

President Donald Trump agrees and promised in December to get that done.

But a consensus that it’s annoying to change the clocks twice a year hasn’t ended the debate. Disagreement has confounded Congress on which solution to pick: standard time, one hour back – or daylight saving time, one hour forward.

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, led a Senate hearing last Thursday to discuss this surprisingly delicate and emotional question.

Arizona and Hawaii are the only states that don’t engage in the twice-a-year clock change, and lawmakers mentioned that with some envy.

“My whole life, we watched Arizona mock us as we all changed our times,” joked Sen. John Curtis, R-Utah, who said ending the clock change would be popular in his state.

Cruz called the clock change “an outdated and harmful practice.”

The 2022 Senate bill would have adopted “permanent daylight time.” That would keep clocks set permanently one hour forward. The bill stalled in the House when lawmakers couldn’t agree on which solution to take.

In December, a month before returning to office, Trump injected further confusion into the issue. He promised that his party would stop the twice-yearly clock change, but took the opposite approach from the Senate’s in its 2022 bill.

“The Republican Party will use its best efforts to eliminate Daylight Saving Time, which has a small but strong constituency, but shouldn’t!” Trump said in a Dec. 13 post on his Truth Social platform.

Daylight saving time came to the U.S. in 1918 when Congress adopted time zones and decreed daylight saving time. The mandatory national clock change proved unpopular and was repealed the following year, with Congress leaving it to each state to decide whether to observe daylight saving time.

In 1966, Congress adopted the Uniform Time Act. Daylight saving time – and the clock change – again became the national default, though states could opt out.

In 2005, Congress adjusted the start and end dates to what we have today: one hour forward at 2 a.m. local time on the second Sunday in March, one hour back on the first Sunday in November, also at 2 a.m. local time.

Backers of the 1966 law cited the potential of energy savings and conservation, as well as “the reduction of crime, improved traffic safety, more daylight outdoor playtime for the children and youth of our Nation” among the benefits.

Those effects turned out to be small and in some cases nonexistent, though, according to a 2020 report from the Congressional Research Service.

David Harkey, president of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, testified to that effect at Cruz’s hearing.

The insurance institute supports measures to reduce nighttime crashes but has found no impact on the number of crashes and fatalities from daylight saving, he said.

Crashes are more likely when it’s dark outside, Harkey told senators, but changing the clock doesn’t change the number of hours of daylight. That’s true on longer summer days and on shorter winter days.

“Our study does not point to a preference for standard time or daylight saving time, based on road safety,” he testified.

Hawaii voted to exempt itself from daylight saving time in 1967.

Arizona voted in 1968 to stop observing daylight saving time. Gov. Jack Williams cited the state’s hot climate and the high cost of energy if daylight were pushed an hour ahead.

The time does change on Navajo land, though. The Navajo Nation’s governing council voted in 1968 to continue observing daylight savings.

Some Arizonans agree that skipping daylight saving works better for them.

Lin Chao, president of the Arizona Trailblazers Hiking Club, said that early mornings are “absolutely” safer for hikers in the summer heat.

“It’s crucial for us to be prepared, especially during our outdoor activities,” she said in an email.

She added that the time difference between Arizona and Utah is “confusing” when trying to coordinate a hike that crosses the state line.

Karin Johnson, a neurologist and sleep doctor from Massachusetts, told senators at the hearing that people would get better sleep if clocks remained on standard time year-round, as they do in Arizona.

For sleep hygiene, she said, the closer the sun is to being overhead at noon, the better.

“Without enough morning light, or with too much evening light, our circadian rhythms delay. This disrupts our sleep patterns and our body and brain functions,” Johnson said.

“The later sunrises and sunsets of daylight saving time allow higher risk for chronic diseases, including, but not limited to cancer, diabetes, heart disease and obesity. … There’s also data that says that permanent standard time also results in better mental health and outcomes, including reducing rates of depression and suicide,” Johnson said.

Jay Karen, CEO of the National Golf Course Owners Association, was more focused on the economic impacts.

According to Karen, golf course owners could lose up to $1.6 billion, or nearly $200,000 per course, if the clock is set back an hour.

“Golf thrives in what we called recreational daylight — the overlap of sunlight and people’s availability to be outdoors. Americans overwhelmingly prefer evening recreation over early morning,” Karen said. “We encourage solutions to preserve evening daylight for golf, for health, for recreation and local economies.”

Some lawmakers indicated that they wouldn’t support a nationwide time policy unless it provides leeway for local preferences.

“States know what’s best for them,” Curtis said.

Scott Yates, founder of the “Lock the Clock” movement, called the clock change “a deadly, outdated relic.”

In his testimony, he urged senators to give states until 2027 to continue changing the clock, after which the twice-yearly switch would end.

Johnson likewise called on Congress to eliminate the clock change.

“Let’s fix a measure of time that actually has meaning where the sun is overhead, and then adjust the social schedule around it,” she said.