WASHINGTON — The millions of people living in the U.S. without documents put stress on emergency rooms and public schools. Some, as President Donald Trump emphasizes, commit crimes.

This population also stimulates the economy. They buy homes, run businesses and provide essential labor for construction and agriculture. Their payroll taxes help to keep the Social Security system afloat.

Trump and others who seek mass deportations focus on the costs of illegal immigration. But short- and long-term costs differ, as do local and federal impacts. And the cost side alone doesn’t give the full picture.

An analysis by the left-leaning Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy showed that people in the country illegally paid roughly $97 billion in federal, state and local taxes in 2022 – almost $9,000 per person.

That includes $25.7 billion to Social Security, even though most will never collect retirement benefits under that program.

“The vast weight of the evidence points to a beneficial effect of immigration,” said Tara Watson, director of the Center for Economic Security and Opportunity at the Brookings Institution. “Including undocumented immigration.”

She acknowledged that taxpayers feel a pinch – especially in the early years of an undocumented immigrant’s time in the U.S.

“For low-educated immigrants who are newly arrived, they tend to have a negative fiscal impact at the local level,” she said. But “they have positive impacts at the federal level.”

Conservative analysts such as Steven Camarota say there’s clearly a “net fiscal drain,” counting costs of education, health care and welfare not only for children and adults living in the country illegally but also for American citizen children born to immigrants.

Apart from stoking fears about the cost to taxpayers and effects on employment and wages, Trump casts immigrants as a danger to society.

But the per capita crime rate among native-born Americans is roughly double that of people in the country illegally, according to the libertarian Cato Institute. Migrants are 26% less likely to commit homicide, for instance.

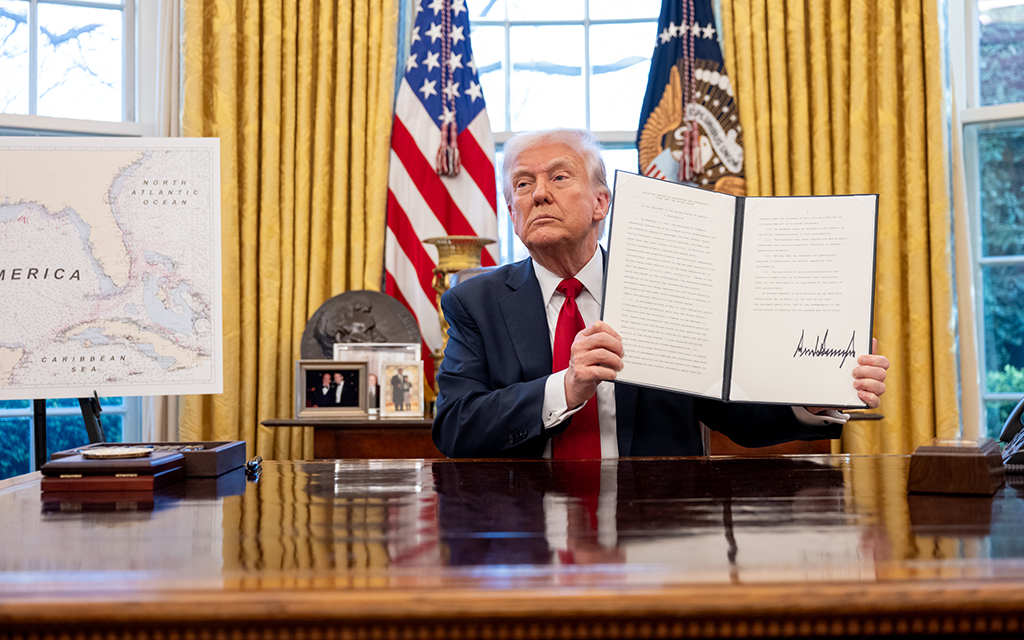

President Donald Trump holds up an order on tariffs on March 26, 2025. (Official White House photo)

Here’s a look at some of the costs and how they are offset by the benefits:

Social Security

There are about 11 million undocumented immigrants nationwide, according to the Pew Research Center. Based on 2022 data from the Census Bureau, Pew says 8.3 million of them are employed.

Like other employees, those who hold a payroll job – the exact number is unclear – pay mandatory withholding of Social Security and Medicare taxes.

Without U.S. citizenship or legal work status, they can’t collect retirement benefits.

Social Security pays current retirees using payroll taxes from active workers. As the workforce ages, the ratio has narrowed. If revenue falls short of liabilities – which current projections say will start in 2035 – the Social Security Administration will have to slash payments unless Congress raises taxes or the retirement age.

Insolvency would come even sooner without workers who pay into the system without hope of drawing from it later.

Health care

Seven states provide health coverage for older immigrants or all residents regardless of legal status.

Twenty-six states provide coverage for pregnant women regardless of immigration status. Thirteen cover children regardless of status, according to the National Immigration Law Center.

But even states that provide no coverage, such as Arizona, still incur health care costs related to the undocumented population. The Federation for American Immigration Reform, or FAIR, which seeks strict limits on immigration, puts the annual cost at $8.2 billion nationwide.

Under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, signed into law in 1986 by Republican President Ronald Reagan, anyone in the U.S. is entitled to emergency care regardless of legal status or ability to pay.

Camarota, director of research at the Center for Immigration Studies, a think tank that supports restrictions on immigration, told a U.S. House committee early last year that one-fifth of government health care expenditures for uninsured patients goes to undocumented immigrants.

That’s $7.5 billion annually nationwide, he testified.

There’s no dispute that lack of insurance is widespread among undocumented immigrants. The National Immigration Forum, a pro-immigrant group, estimates the uninsured rate at 45% to 71%.

At the local level, the fiscal impact can be huge.

Yuma Regional Medical Center spent $26 million in 2022 on uncompensated care for undocumented immigrants, according to testimony the CEO gave in 2023 to a U.S. House committee.

But, recipients of that charity care are appreciative.

Jose Patiño was 6 when his family migrated illegally from Mexico to Phoenix. He recalled several emergency room visits during childhood. He broke his right arm when he was 7 and his left arm when he was 12. At 10, he had a tumor removed.

Now in his 30s, Patiño is part of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. President Barack Obama created DACA to shield people who entered the country illegally as children from deportation.

“To this day, I still feel like I owe the state of Arizona, to the taxpayers, for helping me in a time of need,” said Patiño, vice president of education and external affairs at Aliento, an advocacy group in Arizona.

Welfare programs

The tax code includes provisions aimed at helping low-income families – for example, the Earned Income Tax Credit. Undocumented workers are ineligible for that benefit.

They’re also ineligible for most forms of public assistance in most states.

That includes Medicaid (low-income health care), Medicare (senior health care), the Children’s Health Insurance Program and food stamps.

In his House testimony last year, Camarota estimated that 59% of households headed by an illegal immigrant collect some form of public assistance, mainly through the eligibility of an American-born child in the home.

He estimated the total at $42 billion per year, about 4% of the combined outlay of states and the federal government.

FAIR’s estimate, excluding Medicaid, is $11.5 billion. Like Camarota’s estimate, that includes benefits used by American citizens who live in mixed-status households.

Programs include school meals; Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (food stamps); Women, Infants and Children, a nutrition program for pregnant women, nursing mothers and children under 5; Temporary Assistance for Needy Families; and low-income programs for child care and public housing.

Under the 1996 welfare overhaul signed into law by President Bill Clinton, eligibility is generally limited to U.S. citizens and green card holders – people with permanent legal residence.

Exceptions include refugees, asylum recipients and non-citizens paroled into the country for at least a year, though migrant advocates say that many people who qualify for benefits refrain from signing up out of fear.

States are allowed to provide broader coverage as long as they don’t use federal funds to do so.

In Arizona, undocumented immigrants have limited access to childcare aid and low-income housing programs, plus emergency health care under Medicaid, according to the National Immigrant Women’s Advocacy Project.

“With my family, it was a sense of pride that we didn’t use welfare or … food stamps,” Patiño said.

Public education

About 4 million K-12 students nationwide were children of unauthorized immigrants, according to a 2014 Pew estimate. That was about 7.3% of the school-age population.

The share in Arizona was over 12%. Using the most recent count, that would equate to more than 147,000 students in the state.

In his testimony, Camarota estimated the cost of education for those students – mostly U.S. citizens – at $68 billion a year, plus more for instruction aimed at students for whom English is a second language.

Under a 1982 Supreme Court ruling, Plyler v. Doe, all children – regardless of legal status – are entitled to a free public education.

Some Republicans are angling to get that overturned.

One bill filed in the Tennessee Legislature would let school districts and charter schools “enroll, or refuse to enroll, a student who is unlawfully present in the United States.” Sponsors hope it becomes law so the high court can revisit Plyler.

Republican lawmakers in Texas, Indiana and New Jersey have offered similar proposals. None has passed so far.

K-12 public schools are funded almost entirely out of state and local revenue. In 2024, the federal government spent $34 billion on schools with low-income populations and students with disabilities, according to Pew.

Younger workers

Apart from direct fiscal impacts, economists and migrant advocates point to the role immigrants play in replenishing the labor supply as the American workforce ages.

According to the Migration Policy Institute, 77% of immigrants are of working age, compared to 58% of U.S.-born citizens.

Labor shortages would be a real possibility without the influx of workers, economists say. Trump’s deportation efforts would impact a number of sectors, especially construction and agriculture.

“Immigrants are good for the economy,” Watson said, though she added, “it doesn’t seem to be an argument that a lot of people are receptive to.”

Patiño got his first job in construction when he was in seventh grade, at his parents’ urging.

“What they would say is, `You came to the U.S. to work,’” he said. “`Your parents have made so many sacrifices, and they have given up so much. … We came here to have success; we didn’t come here to do anything else.’”