WASHINGTON – The 1798 law President Donald Trump dusted off to justify the swift deportation of Venezuelan gang members hadn’t been invoked since World War II – when it was used to justify internment camps for Japanese Americans.

More than 100,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry were forced from their homes. Two of the camps were in Arizona and became, for a time, the state’s third and fourth biggest cities: Gila River, with a population that hit 13,000; and Poston, which held more than 18,000 at its peak.

Trump’s rare use of the Alien Enemies Act triggered memories of that dark chapter, along with outrage and fear as the president declared that an “invasion” is underway involving the Tren de Aragua criminal organization.

That, according to the White House, provided a legal basis to deny hearings for the 238 migrants flown to El Salvador last weekend in defiance of a federal judge.

Saburo Kido (far right), National President of the Japanese American Citizens League, a civil rights group, with other lawyers at Poston Camp Number 1 in Poston, Arizona, on Jan. 4, 1943. (War Relocation Authority photo from the National Archives)

“President Trump is making quite the stretch to make this apply to this situation,” said Stuart Streichler, a University of Washington political scientist.

Until now, the law had only been used during the War of 1812 and the two world wars.

The second president, John Adams, signed the law at a time when the U.S. and France were on the brink of war and concern was rising about French sympathizers.

During World Wars I and II, the Alien Enemies Act was used to justify detention, expulsion and surveillance of immigrants from Germany, Italy and Japan – along with American citizens with ancestry in those nations.

Less than three months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt invoked the law when he ordered the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast on grounds they posed a national security threat.

Detainees in Poston – a remote site 90 miles north of Yuma, just across the state line from California – nickname the three subcamps “Roast ‘em, Toast ‘em and Dust ‘em” due to the insufferable heat.

At both Poston and Gila River, multiple families were crammed into small military barracks with no ventilation or insulation. Health care was scarce.

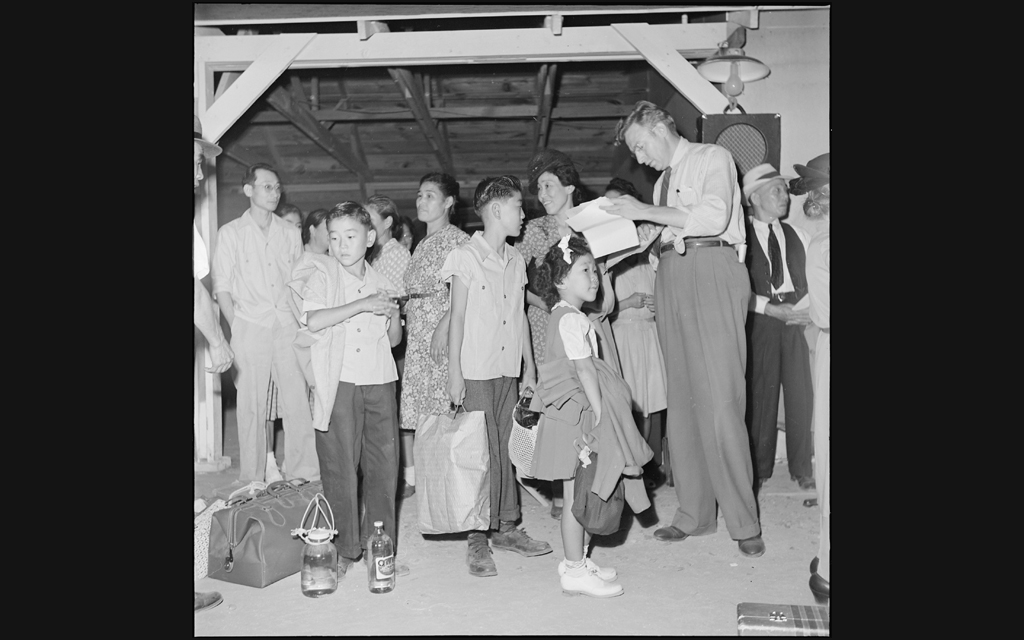

Japanese Americans arrive at the Colorado River Relocation Center, Camp 1, in Poston, Arizona, on May 20, 1942. President Franklin D. Roosevelt invoked the Alien Enemies Act to justify the detention of more than 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry, many of them U.S. citizens, during World War II. (War Relocation Authority photo from the National Archives)

“Imagine a state in which two of the four largest cities are concentration camps,” the poet Brandon Shimoda, grandson of a prisoner, said in a 2017 speech at the Jewish History Museum in Tucson. “That was Arizona in the 1940s: Phoenix, Tucson, Poston, Gila River.”

Marlene Shigekawa, a writer and documentary filmmaker who was born in captivity in Poston, said survivors of the camps are aghast that Trump has invoked the same law that brought their families so much suffering.

“It’s very unsettling for the Japanese American community,” Shigekawa said. “Many still haven’t processed what has happened. The act taps into fear.”

Shigekawa is executive director of the Poston Community Alliance, a nonprofit that preserves the legacy of the camp. She has worked for over 15 years with the Tribal Council of the Colorado River Indian Tribes to preserve historic structures and create educational films.

“For those of us that have fought hard to educate, it just makes us more enraged and willing to continue the fight,” she said. “It motivates me to do more, to educate people as we always try to do.”

The text of the Alien Enemies Act allows its use only in case of a “declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion … by any foreign nation or government.”

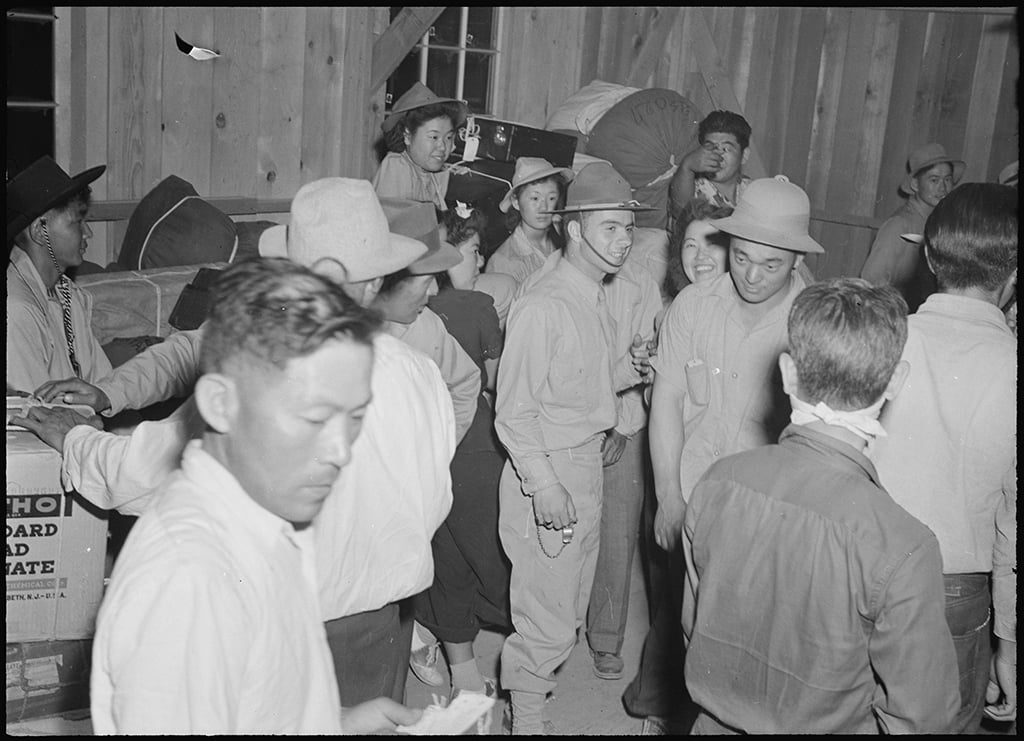

A view at a Thanksgiving dance given at camp #2 on Nov. 26, 1942, at the Gila River Relocation Center in Rivers, Arizona. (War Relocation Authority photo from the National Archives)

By law, only Congress has the authority to declare war.

But Trump’s proclamation asserts that Tren de Aragua is a terrorist group so entrenched in Venezuela’s government as to be part of it. Its members, he asserted, “have unlawfully infiltrated the United States and are conducting irregular warfare and undertaking hostile actions against the United States.”

Critics say the argument is thin. The American Civil Liberties Union and Democracy Forward have challenged Trump’s use of the act in federal court.

And Trump didn’t need to stretch the Alien Enemies Act, Streichler said, because “he’s got enormous powers to address immigration. Any U.S. president does.”

He questioned the wisdom of invoking such sweeping powers, citing the lessons of the internment camps. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed a law providing $20,000 to each detainee and an official apology for the injustice of the forced displacements and internment.

“It’s a big question about civil liberties when this act is used,” Streichler said. “Whenever it has been used … looking back at it people think, ‘Did we overreact? Was that really necessary?’”