WASHINGTON – Many oil and gas wells across Arizona with no known owners leak methane into the environment, which tribal, state and federal agencies are responsible for cleaning up.

These wells – referred to as “orphaned” – are often not properly maintained and can lead to surface and groundwater contamination causing pollution, health issues and threats to wildlife.

“For over a century, oil and gas companies have set up their drilling operations across Arizona, taken what they wanted and then skipped town, leaving their dangerous equipment and toxic mess for someone else, namely American taxpayers, to deal with and pay for,” Rep. Raúl Grijalva, the ranking member of the House Natural Resources Committee and an Arizona Democrat, said in a statement.

Orphaned oil and gas wells do not have owners legally responsible for plugging, or closing, the wells. Although they are no longer in use, without a cap, they continue to emit methane.

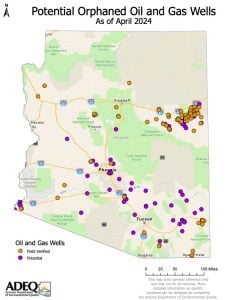

The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality has identified roughly 200 potential orphaned oil and gas wells around the state.

Potential and verified orphaned wells, as of April 2024, spread out across Arizona with a collection in the northeastern part of the state. (Map courtesy of the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality)

“We’re a very lucky state in that we’re not like Texas or Louisiana or Ohio; we don’t have hundreds of thousands of these – we have hundreds,” said Tina LePage, remedial projects section manager for the ADEQ.

Nationwide, nearly 4.6 million Americans live within a half-mile of an abandoned mine or well, according to the Environmental Defense Fund, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group.

“Any orphan well is a health issue,” said Hazel Chandler, a field coordinator with the Arizona chapter of Moms Clean Air Force, a climate advocacy group. “We’re at a choice point – if we don’t act on addressing the amount of pollutants we’re putting in our air, very quickly our planet will continue to unravel.”

In addition to the environmental impacts of the well, costs associated with remediation are also a concern.

Curtis Shuck, founder of the Well Done Foundation, an organization focused on plugging wells, believes oil and gas companies should be held accountable to limit federal funding needed for remediation.

“I felt very strongly, and we still do as an organization, that this isn’t a taxpayer responsibility. The taxpayer didn’t get us into this trouble, taxpayers shouldn’t have to bail us out,” he said.

When the ownership of oil or gas wells is untraceable, the remediation responsibility falls to federal, local or tribal governments.

The Department of the Interior (DOI) and the Department of Agriculture oversee wells on federal lands. In Arizona, the ADEQ runs its own remediation program with the Arizona Oil and Gas Conservation Commission for wells on state and private property. Tribal nations in the state are responsible for remediation on their lands.

Both the ADEQ and the Navajo Nation have received federal funding from the Biden-Harris administration. Shuck said federal funding acts as a bailout and isn’t a long-term solution.

The state was granted $25 million in 2022 from the DOI. The grant will fund the Orphaned Oil and Gas Well Program, which began in October 2022 and will run until December 2025.

The program is locating potential orphaned wells, plugging the wells using cement to seal off areas where oil and gas are found within the well and then remediating the site if the surrounding landscape was significantly disrupted.

“We’re trying to maximize the funding we have for the plugging of those wells. We anticipate utilizing every one of those dollars to finish as many of the wells as possible,” LePage with the ADEQ said.

To date, the ADEQ has located 80 wells with 38 of them in line to be plugged, LePage said.

Identifying and locating the wells is phase one of a four-phase program the ADEQ will run until the end of 2025.

In late August, the DOI awarded the Navajo Nation $5 million to plug 19 identified wells.

Additionally, Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren signed a memorandum of understanding with the Department of Energy outlining their willingness to work together and plug orphaned wells across the tribal nation.

“While all of us are forced to bear the financial burden, it’s the nearby communities, many of which are tribes, that disproportionately face the health issues caused by contaminated water wells, leaking methane, and other environmental hazards in their day-to-day lives,” Grijalva said in a statement.

Even after production halts, an orphaned oil or gas well can still emit methane and other pollutants into the atmosphere. The wells can contaminate water supplies and lead to health issues. (Photo courtesy of the Department of the Interior)

Shuck, founder of the Well Done Foundation, noted that “orphan wells don’t discriminate, they’re everyone’s problem.” However, wells located in lower-income communities tend to move to the top of the priority list for the organization.

The Bureau of Land Management, one of the DOI bureaus responsible for remediation, only had one well on its federal land in Arizona. The bureau completed remediation of the well last summer, said Rem Hawes, a spokesperson for the Arizona office of the BLM.

Matt Warren, senior petroleum engineer at BLM, said the bureau’s orphaned well determination process is different from the process state agencies take. The BLM is able to trace more records and hold past owners accountable. This minimizes the number of wells needing remediation from the federal government.

“For orphaned wells, we don’t have a lot right now because of that process and because of the different tools that we have to protect taxpayers from having to plug everything for these wells,” Warren said.

Grijalva said the funding from the Biden-Harris administration is an improvement, but plugging orphan wells is “a problem that the American people shouldn’t be forced to fix in the first place.”

“It’s time for us to hold oil and gas companies accountable for paying to clean up their own messes,” Grijalva said in his statement.

Shuck also asked for accountability but said remediation still needs to be done.

“This is really about doing the right thing and cleaning up after ourselves, or cleaning up after others who didn’t clean up after themselves,” Shuck said.