WASHINGTON – The first shipment of uranium ore from the new Pinyon Plain Mine near the Grand Canyon began rumbling through Navajo land on July 30 – outraging tribal leaders.

They knew the shipments were coming, but had expected a heads-up from Energy Fuels Inc., especially given the tribe’s painful history of radiation exposure from uranium mining and nuclear bomb tests.

In late August, the Navajo Nation Council adopted legislation requiring a week’s notice before any future shipment from the mine to a mill in southern Utah.

The company is taking steps to appease the tribe. It has promised notice before future shipments, and is negotiating voluntary transit fees, even though tribal officials concede they can’t enforce the demands.

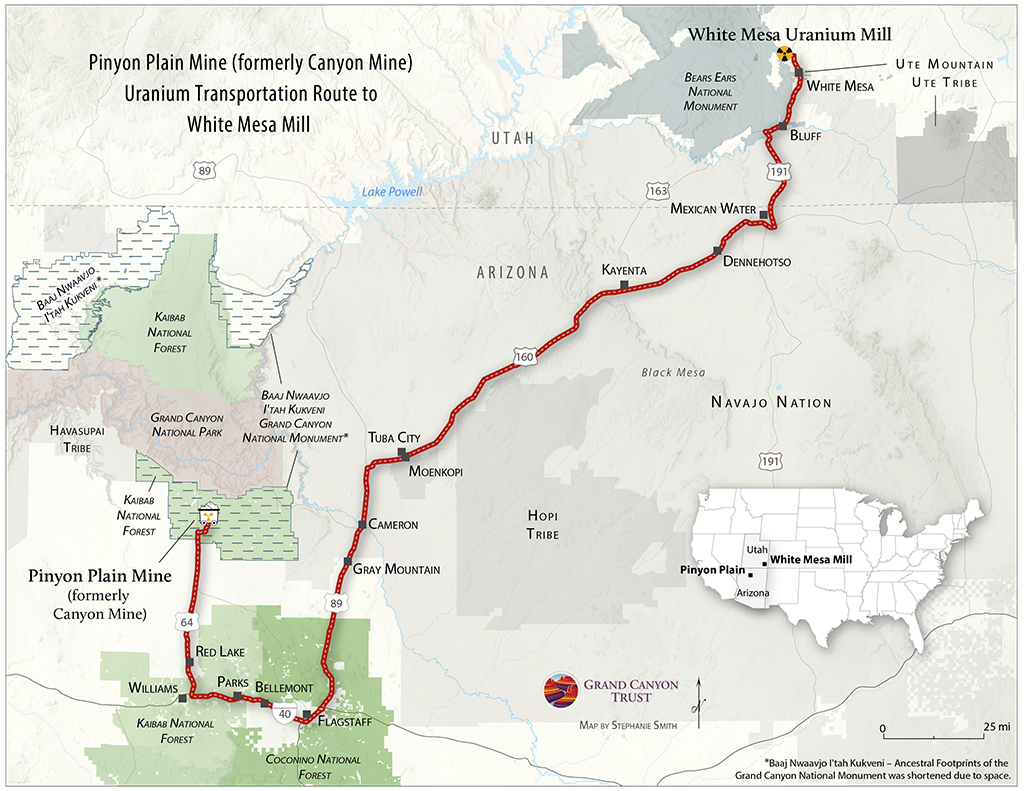

The route goes through about 120 miles of Navajo lands, passing Cameron and Tuba City. But the tribe has no enforcement authority to prevent or regulate the shipments on U.S. 89 and U.S. 160, federal highways maintained by Arizona.

The Diné’s experience with uranium has left them wary, said Justin Ahasteen, executive director of the Navajo Nation Washington Office.

“The Navajo Nation has taken a firm stance that we will never be exploited like this again. We never want to have anything to do with this dangerous radioactive element ever again,” he said.

From 1944 to 1986, over 30 million tons of uranium were mined on Navajo land. Thousands of Diné worked in the mines, and almost 600 died of lung cancer by 1990, according to federal records.

The route used by Energy Fuels Inc. trucks carrying uranium ore from Pinyon Plain Mine to White Mesa Mill for processing in Utah. The route passes through Flagstaff before heading northeast through Navajo Nation land. (By Stephanie Smith/Grand Canyon Trust)

There are 523 abandoned uranium mines on or near Navajo land, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Plans are underway to address contaminated water and other hazards, the EPA says. Before the new mine opened, U.S. uranium mining had been halted for eight years amid a global demand slump.

“It’s understandable why they’re particularly sensitive about this issue,” said Steve Nesbit, a former president of the American Nuclear Society, though he emphasized that truckloads of ore pose no risk.

Curtis Moore, senior vice president of marketing and corporate development for Energy Fuels Inc., said the company has volunteered to help with the overdue mine clean-up, even though it had nothing to do with those sites.

“Every level of what we do we go above and beyond what’s required by the laws and regulations,” he said. “We’re having some good, productive discussions with the Navajo Nation right now to see if there’s anything more we can do to allay their concerns.”

That includes negotiating fees for ore shipments through the reservation.

“They don’t have the right to require it, but we’re open to doing it voluntarily,” Moore said, who added that the ore poses no risk to people along the route. “We’re already following the very stringent, protective U.S. Department of Transportation regulations.”

Navajo officials agree that talks with the company have been going well.

And they concede a lack of jurisdiction, stemming from a 1997 ruling in a case known as Strate v. A-1 Contractors.

The case involved a collision in North Dakota on a section of state highway passing through tribal land. A tribal court denied a request to dismiss the case by a trucking company whose driver was involved in the crash. A unanimous U.S. Supreme Court ruled the tribal court had no jurisdiction.

“They essentially indicated that state right-of-ways are not subject to tribal jurisdiction,” Ahasteen said, adding that the tribe disagrees with the ruling. “This case really just impacted a tribe’s ability to self-govern and self-regulate.”

Ahasteen called it “a gesture of goodwill and good faith” for the company to cooperate with the Navajo Nation “despite what that Supreme Court ruling says.”

The route taken by Energy Fuels Inc. trucks carrying uranium ore from the Pinyon Plain Mine near the Grand Canyon to White Mesa Mill in Utah goes through over 120 miles of Navajo Nation land. (Photo by Walter Bibikow/Getty Images)

Moore attributed some of the uproar to misconceptions about uranium ore.

“There’s a lot of these minerals and materials that when you dig them up out of the ground are naturally radioactive,” he said. “They’re not highly radioactive.”

The element occurs naturally in the Earth’s crust at 2.8 parts per million.

Nesbit described uranium ore as dirt and rocks with an above average concentration – around 0.1%, which means that a ton of ore yields 2 pounds of uranium.

Less than 1% of that is uranium-235 – the isotope used in nuclear reactors and bombs. The rest is uranium-238. On average, that ton of ore contains just 0.32 ounces of fissile material, a tiny fraction of the 11 to 22 pounds needed for a bomb. Getting that much would require at least 550 tons of ore.

“Uranium is radioactive but it’s very mildly radioactive. It doesn’t have a lot of what we call penetrating radiation associated with it,” Nesbit said. “Just standing next to a bunch of uranium ore isn’t hazardous at all.”

The biggest hazard with mining is actually the radon gas emitted by the ore, he said.

The gas can build up without proper ventilation. Radon is odorless and radioactive and causes lung cancer with prolonged exposure. It’s found in soil in all 50 states, according to the EPA, and one in 15 homes nationwide has elevated levels.

Modern mining practices and protective gear effectively eliminate the risk to miners, Nesbit said, and any radon emitted from a truckload of ore is no danger to anyone.

“It’s such a small amount and the atmosphere is so huge that it just … doesn’t pose a health hazard,” he said.