WASHINGTON – From 1819 until 1969, hundreds of thousands of Native American children were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to boarding schools – sometimes hundreds or even thousands of miles from their families.

The schools were run by churches and the federal government with a clear purpose: to strip Native Americans of their cultures and force them to assimilate.

Abuse was rampant. Overcrowded and unsanitary, the schools became breeding grounds for tuberculosis and other diseases. An estimated 40,000 children died in these boarding schools.

Arizona was home to 59 of these schools.

A move is underway in Congress to bring accountability to the federal government for promoting these policies.

“We cannot rectify the past until we face it head-on,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Massachusetts, said Wednesday evening on the Senate floor as she and a handful of colleagues held forth on the topic. “There isn’t an indigenous community in this country that hasn’t been affected.”

A bipartisan bill that currently has 32 Senate co-sponsors would create a “Truth and Healing Commission” akin to those used in post-apartheid South Africa and in other places affected by conflict.

The commission would investigate Native American boarding schools and the lasting impact they had on families and tribal communities. It would hold hearings to gather witness testimony, and would have subpoena power to dig out documentation and unshroud a history that churches and governmental entities have kept hidden for decades.

The commission would also make recommendations on whether the dark history of these schools should shape current federal policy.

Warren introduced the bill with Sens. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, and Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii. Both senators from Arizona are co-sponsors: Independent Kyrsten Sinema and Democrat Mark Kelly.

Only Oklahoma had more Native American boarding schools than Arizona, according to lists compiled by the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

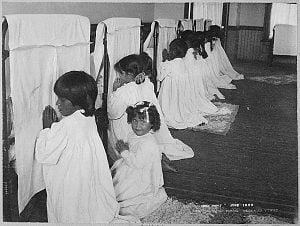

Native American girls at the Phoenix Indian School. Photo dated June 1900. (Photo courtesy of National Archives)

“It’s cheaper to educate Indians than to kill them,” Thomas Morgan, the federal Indian Affairs Commissioner appointed by President Benjamin Harrison, said at the establishment of the Phoenix Indian School in 1891.

As Captain Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania – which became the model for government-run boarding schools – infamously said, “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

The education these schools provided was often inadequate.

Children were hit, slapped and starved if they dared to speak their native languages, practice their religion or display any behavior that indicated a resistance to assimilation.

There was also sexual assault.

A recent Washington Post investigation identified 122 priests and student workers at 18 schools alone who had been accused of molesting Native American children under their care. The perpetrators rarely faced repercussions and were instead often moved to other schools. The Catholic Church sent priests to facilities such as the Servants of the Paraclete in New Mexico, set up for clergy with “personal difficulties.”

Sen. John Hickenlooper, D-Colorado, recounted incidents in his own state. Fort Lewis College used to be known as the “Fort Lewis Boarding School,” he recounted as he, Warren and others held the Senate floor to spotlight their commission proposal.

Dr. Thomas Breen, superintendent at Fort Lewis, was known for raping girls at the school, the senator said, and staff were instructed to make any student who became pregnant “disappear.”

“Why was our government preying on our own children?” Hickenlooper said during his impassioned floor remarks.

“We have not simply a moral responsibility, but a legal obligation to the welfare of tribes across the country to uphold treaty rights, and to recognize the dark history of our own country,” he said. “This obligation cannot be met without securing truth, justice and healing for every Native person, family and tribe affected by these genocidal policies.”

Native American parents who refused to give up their children were incarcerated or had their food rations cut off by the U.S. government.

Warren spoke about armed men sent onto reservations to pry children from their families, some as young as 4.

“If I was a parent, I would be absolutely catatonic,” Schatz said.

Many of these parents would never see their children again.

At least 53 mass graves containing the remains of Native American boarding school children have been found after an investigation launched by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland – the first Native American to hold a Cabinet position.

Haaland’s own parents had been forced to attend these boarding schools.

It’s unclear how many living survivors of the boarding schools remain. Warren and others called it urgent to let them tell their stories before it’s too late.

“Most of those affected have passed away. But there are remaining survivors in their 60s, 70s and beyond,” Warren said. “These people have been harmed enough. Their wounds go deep, and they deserve a chance to stand before the United States government and tell their stories.”