WASHINGTON – U.S. Customs and Border Protection has reported a sharp drop in the use of force against migrants at the southern border since last summer – 27% for the 12 months that ended May 31 – compared to a year earlier.

Migrant advocates are skeptical.

The Government Accountability Office found significant underreporting in a report issued last July. One practice GAO spotlighted was counting an incident as a single event even when it involved numerous CBP officers and dozens of migrants.

CBP defends its record on use of force and its methods for tracking such incidents, and says officers use force only when necessary. The agency doesn’t release incident reports unless an internal review finds excessive use of force.

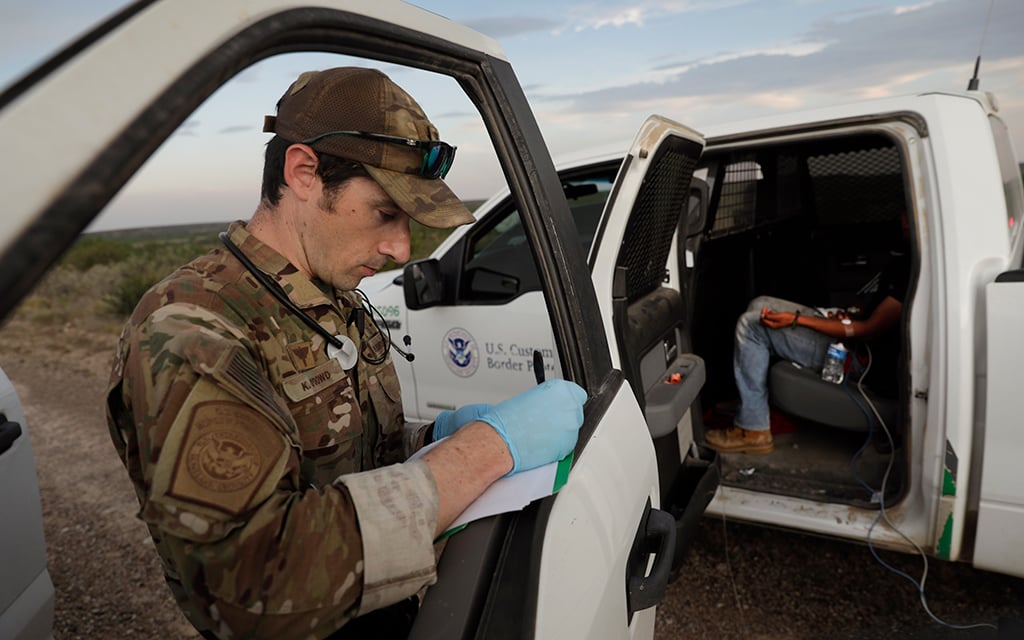

A U.S. Border Patrol Search, Trauma, and Rescue (BORSTAR) agent creates a medical report near Eagle Pass, Texas. (Photo by Glenn Fawcett/CBP)

“If the use of force was justified, there’s nothing that needs to happen,” said John Mennell, CBP spokesperson.

The internal reviews often take years. Migrants rarely file a formal complaint. Those who do are often deported long before the internal review takes place, advocates say, so the alleged victims rarely get a chance to dispute the official version.

“It is hard to tell someone who has just experienced an abuse by Border Patrol that they should file a complaint, only to explain to them that in the vast majority of cases, we never hear anything back,” said Zoe Martens, a migrant advocate who worked at Nogales-based Kino Border Initiative until recently.

“First, a migrant person experiences this abuse, and then the detailed testimony they gave explaining the mistreatment disappears into an opaque web of accountability offices and their databases,” she said.

From June 2023 to the end of May 2024, CBP reported 762 instances of use of force at the U.S.-Mexico border.

The tally for the 12 months prior was 1,039 – even as encounters with migrants increased. But the nature of those encounters has changed. For the same timeframe, the number of families was up nearly 60% while the number of single adults dropped by almost 20%.

“In the previous year you saw a lot of evasion traffic through the mountains and through the deserts,” Mennell said. “When migrants are surrendering to be processed, they’re not fighting, there’s no use of force. It’s that simple.”

“Somebody with a baby in their arms is not going to assault an agent,” he said.

Encounters dropped over 40% in the three weeks since President Joe Biden’s executive order June 4 to bar migrants who cross unlawfully from seeking asylum, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas announced in Tucson on Wednesday.

The department hasn’t released data on the use of force in June.

Friction tends to drop with the number of encounters. But advocate groups aren’t convinced they can trust CBP to accurately report such incidents.

“They’ve got a ways to go to earn the trust of the American people,” said Andrea Guerrero, executive director of Alliance San Diego, which provides legal aid to immigrants.

The 2023 GAO report examined use of force reports in fiscal years 2021 and 2022.

The government auditor found widespread undercounts.

Out of 1,700 incidents, over 500 involved multiple migrants or multiple officers. Some were counted as a single incident, though it’s unclear how often that occurred. In one instance recorded as a single incident, four Border Patrol officers used force against 62 migrants.

By contrast, CBP has used the opposite approach to inflate the dangers posed by migrants. In 2018, The Intercept uncovered a practice of counting assaults against officers by multiplying the number of officers assaulted by the number of attackers – rather than counting the injury of one officer as a single incident.

Rebecca Sheff, senior staff attorney for ACLU New Mexico, is among the migrant advocates who takes a skeptical view of the self-reported data.

CBP relies “on internal accountability measures as opposed to opening itself up to public scrutiny,” she said.

The data doesn’t differentiate between the use of tasers, pepper spray, batons and other non-lethal measures.

The agency says that under current practices, an incident involving one agent and three migrants would be counted as a single incident. Likewise, the agency says, “five subjects throwing rocks at three CBP agents or officers is counted as one incident.”

Arturo Del Cueto, a Border Patrol officer in the Tucson sector and national vice president of the officers’ union, the National Border Patrol Council, said people who accuse the agency of using force without justification can’t back that up.

They “just flat out say, ‘Well it’s wrong,’ without showing the proof,” he said.

Migrant advocates say they don’t trust the thoroughness and accuracy of use-of-force reports in part because agents have not always been truthful about such incidents.

A group of migrants is apprehended by Yuma Sector Border Patrol. (Photo by Jerry Glaser/CBP)

Anastacio Granillo, then 63, an American citizen from Deming, New Mexico, was returning from a visit with family in Mexico on June 18, 2019. He arrived by car at the state’s port of entry in Columbus.

According to his own report later, Granillo declared allergy medication he was bringing across the border. The medication fell when he handed it to Officer Oscar Orrantia to inspect.

What happened next would end with the officer convicted in federal court last December for falsifying records and making false statements in his report. He faces 10 to 20 years in prison.

Orrantia ordered Granillo out of his car, and when he didn’t comply, reached in, unbuckled the seatbelt and threatened him with violence unless he got out.

According to Granillo, the officer became enraged when he tried to read the officer’s name tag. Orrantia testified that he thought Granillo intended to make a complaint about him.

Once out of the car, Orrantia “grabbed and twisted Mr. Granillo’s right arm behind his back and slammed Mr. Granillo against the wall of the inspection bay,” according to a complaint filed by the ACLU of New Mexico.

Granillo fell and hit his head during the scuffle. He was then detained, though he was not charged with committing any crime.

Orrantia’s report on the incident omitted so many details of his use of force that he ended up facing serious charges.

Migrant advocates consider the case an outlier not because of the assault by law enforcement, but because it came to light. And that was largely because the victim was American and made the effort to pursue justice.

“We don’t have visibility on their self-reports unless it’s part of litigation,” said Guerrero, the Alliance San Diego official. “There’s a problem with self-reporting and a lack of standardization – a lack of integrity to the data itself.”