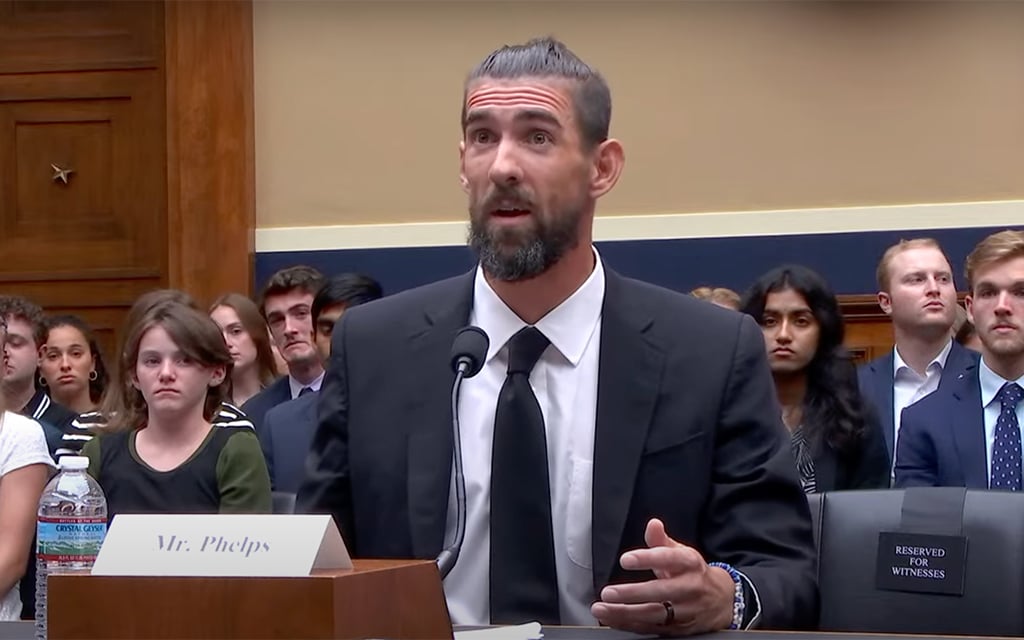

WASHINGTON – Swimmer Michael Phelps – the most decorated Olympic athlete in history – pressed Congress to demand an international crackdown on doping amid revelations that 23 Chinese swimmers tested positive for a banned substance before the Tokyo Olympics in 2021.

The World Anti-Doping Agency knew about the test results but allowed the swimmers to compete. Last week, 11 of those swimmers were named to the Chinese team for the Paris Olympics, which start July 26.

U.S. anti-doping officials, athletes and lawmakers consider that an outrage, and a sign that WADA needs reform.

Olympians should be able to look at a competitor and think, “Alright cool, this is me versus you, it’s not me versus you and seven other drugs,” Phelps told lawmakers at a Tuesday night hearing of the House Energy and Commerce oversight subcommittee.

With 23 Olympic gold medals plus five others, the Arizona resident brought star power to a hearing intended to put pressure on WADA and to shame China, a U.S. adversary.

“I was once a kid with a dream, and by continuously showing up and putting in the work, I was able to make my dream a reality. But I was only able to do so because I had faith that I was being given a fair shot on the world stage.” – @MichaelPhelps pic.twitter.com/jfcLd4pGUg

— Energy and Commerce Committee (@HouseCommerce) June 26, 2024

“It is rather frustrating that, over time, I never have felt like I was competing in a clean field,” Phelps testified, adding later, “If we continue to let this slide any farther, the Olympic Games might not even be there.”

Nearby at the witness table was his friend Allison Schmitt, a 10-time Olympic medalist, who also spent much of her swimming career in Arizona.

“As Olympians, we adhere to strict protocols,” she told lawmakers – and those efforts are “rooted in a belief that fair competition is worth every sacrifice.”

The Olympians, alongside U.S. Anti-Doping Agency CEO Travis Tygart, called on Congress to consider withholding U.S. funding to WADA if necessary to force tougher repercussions – especially with countries like Russia and China.

Tygart called both countries “too big to fail” in the eyes of the world sporting community – a phrase applied to certain banks that U.S. regulators deemed essential during the 2008 financial meltdown.

WADA was established in 1999 as an independent agency meant to guard against athletes taking performance-enhancing drugs.

The U.S. provides $3.6 million a year to the agency, more than any other country. Only the International Olympic Committee itself provides more.

The New York Times reported in April that six months before the Tokyo Olympics – the postponed 2020 Games due to the COVID-19 pandemic – 23 Chinese swimmers tested positive for trimetazidine, or TMZ. TMZ is used to treat conditions like angina by increasing blood flow to the heart. The drug can help endurance athletes because of its effects on blood pressure and metabolic rate.

“This drug is such a potent performance-enhancing drug,” Tygart testified, “it’s banned at all times” – that is, during both competition and training throughout the season.

The Chinese Anti-Doping Agency, CHINADA, reported the positive test results to WADA two months later without taking action. Chinese authorities said the athletes were inadvertently exposed.

WADA had the option to appeal to an arbitration body. After consulting with outside lawyers, it also determined that no action was warranted.

The FBI looked into the allegations after it learned about the positive tests in the last year or so, according to The Times.

The House subcommittee invited WADA president Witold Bańka to testify. He declined.

The agency released a statement Wednesday saying the hearing “sought to further politicize a relatively straightforward case.” WADA also said it did not want to “risk prejudicing the ongoing independent review” of the case by a Swiss prosecutor.

Phelps and Tygart testified before Congress in 2017 following similar doping allegations against members of the Russian Olympic team. Phelps expressed disappointment Tuesday that the 2017 hearing wasn’t the first and last on the subject of Olympic doping. He also decried the lack of “rule following” since then.

Rep. Debbie Lesko, R-Peoria, asked Tygart if the U.S. should withhold funding to WADA until it makes public the Chinese case file on the swimmers found to have been doping.

“We have to have the leverage we need,” he responded.

Lawmakers across the political spectrum denounced doping as a stain on the spirit of the quadrennial Games.

Under a law enacted in late 2020 – the Rodchenkov Anti-Doping Act, named for a whistleblower who brought attention to Russian doping – the Department of Justice has authority to prosecute anyone involved in doping at international competitions even if they live outside the United States.

Phelps recalled in his testimony that in 2016, he submitted to roughly 150 drug tests while entire teams from some countries were tested just 30 or 40 times.

He won five gold medals and one silver that year at the 2016 Games in Rio De Janeiro, then retired with 28 medals, more than any Olympic athlete in history.

Phelps moved to the Valley in 2015 to follow his legendary mentor Bob Bowman, who was head swim coach at Arizona State University until this past spring, when he moved to the University of Texas at Austin as the director of swimming & diving and head coach of the men’s team.

Schmitt swam for the U.S. in the 2008, 2012, 2016 and 2020 Games, collecting four gold medals and a half-dozen others. She received her master’s degree in social work from ASU.