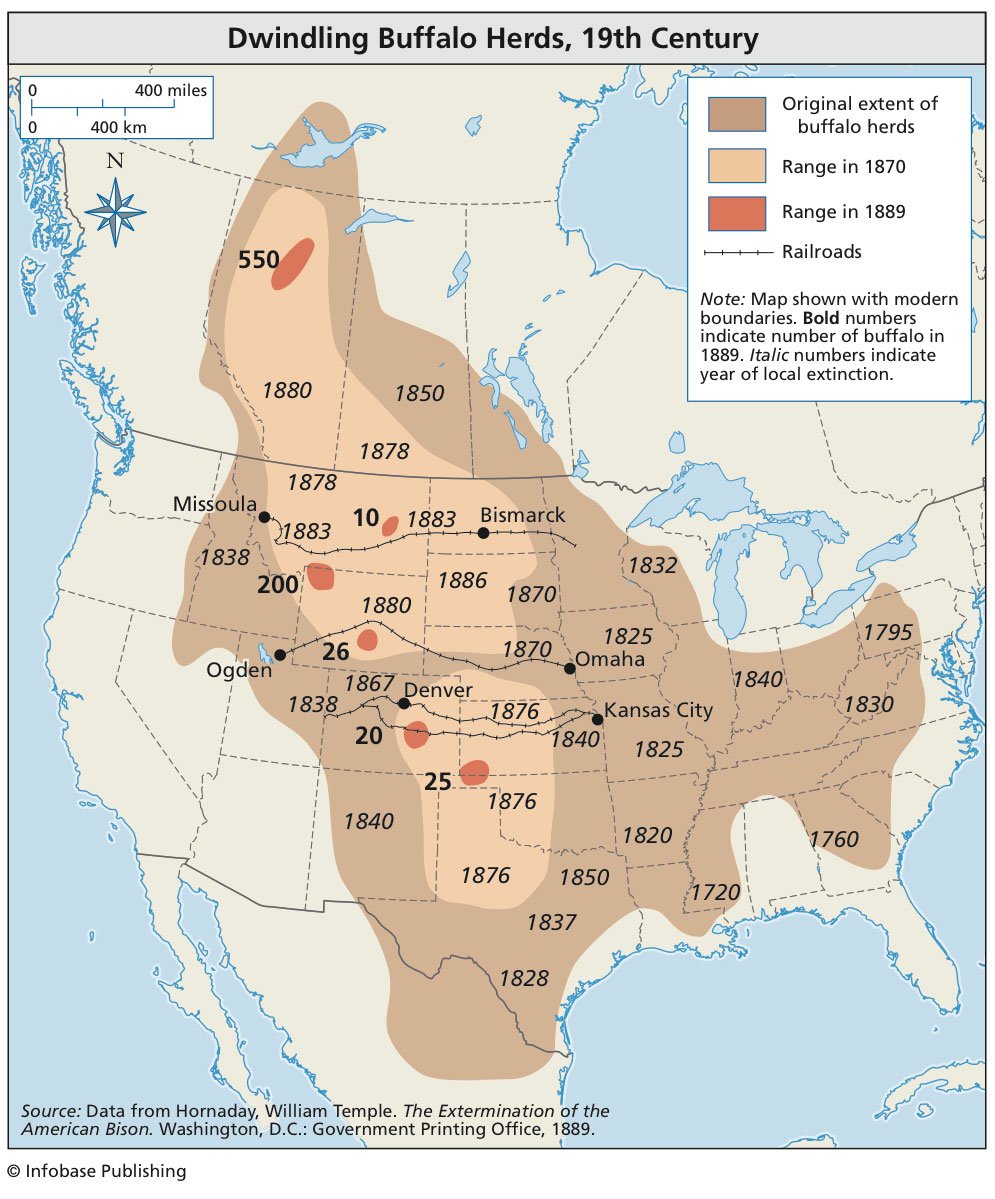

WASHINGTON – Buffalo are so iconic, Congress designated them as the national mammal in 2016. Native American oral histories estimate that 30 to 60 million once roamed the plains.

After nearly going extinct, the shaggy beasts are making a comeback and soon, many could find themselves on reservations where their kind hasn’t set hoof in decades.

A bipartisan bill pending in Congress would pay to relocate some of the 20,500 buffalo from public lands across the West and Midwest to reservation lands that were historically part of the animals’ range.

By the early 1900s, fewer than a thousand remained. The latest headcount is roughly 440,000 nationwide, mostly in commercial herds, according to the Interior Department. Over 4,000 wild buffalo live in Yellowstone National Park.

Support for moving some back to their ancestral lands shows signs of growing since the late Rep. Don Young, an Alaska Republican, proposed it in 2021. The House approved the measure 373-52 in late 2021 but it died in the Senate.

Sen. Markwayne Mullin, R-Okla., the only Native American in the Senate, is leading a new push with Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-N.M.

The bill would ensure that Native Americans “continue reconnecting with a keystone of their historic culture and way of life,” Mullin said in a press release announcing the measure.

Buffalo are actually a species of bison. The terms are interchangeable in the United States, where French fur trappers began calling them “boeuf” (beef) in the 1600s and the name stuck.

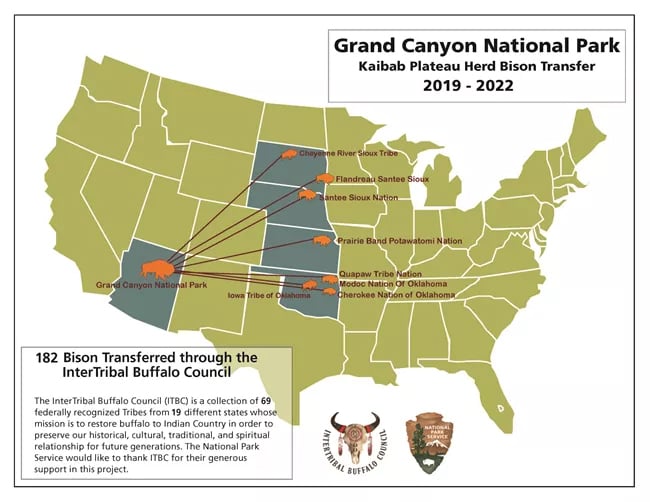

(Map courtesy of National Park Service)

Before Europeans arrived, “all Natives in this country depended on the Plains buffalo for survival…. Buffalo were essential to the Native lifestyle and provided food, shelter, clothing – essential tools for our way of life,” Ervin Carlson Sr., president of the Intertribal Buffalo Council, said at a June 12 Senate hearing on the proposed relocation.

“They symbolize survival, and became essential to our spirituality and religious practices. Our people referred to the buffalo as ‘my relative,’ to signify how spiritually we’re connected to them,” Carlson, a member of the Blackfeet Nation in Montana, told senators.

Unconstrained hunting by white settlers contributed to the disappearance of buffalo. Some herds were killed to make way for railroads – collisions would have been very problematic – and the U.S. military slaughtered buffalo to deal with the so-called “Indian problem.”

In 1875, a bill was proposed in the Texas Legislature to preserve the species by limiting the hunting of buffalo. Gen. Philip Sheridan, assigned by President Ulysses S. Grant to “pacify” the Great Plains, defended the slaughters as more effective than the fighting of the previous 40 years.

“They are destroying the Indians’ commissary.… let them kill, skin and sell until the buffalo are exterminated,” he said.

With the buffalo decimated, tribes lost food, clothing, a way of life and their independence.

The loss of buffalo also contributed to starvation and genocide. There were millions of Native Americans in North America before Christopher Columbus arrived and introduced Europeans to the New World. By the 1920 census, only 250,000 remained in the United States.

The draft of Mullin and Heinrich’s bill, the Indian Buffalo Management Act, acknowledges that “buffalo were nearly exterminated by non-Indian hunters in the mid-1800s.”

Tribal leaders have long wanted to reestablish herds. Proponents of the bill are hopeful that a future with shaggy-haired beasts roaming Indigenous lands in abundance is closer than ever.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, there are about 440,000 buffalo in the United States. Approximately 20,000 are in conservation herds, including a herd at the North Rim of the Grand Canyon under the care of the National Park Service, Arizona Game and Fish Department and the Kaibab National Forest.

Since 2018 the Intertribal Buffalo Council, or ITBC, has relocated 182 buffalo from the North Rim to eight tribes in South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma.

The relocations are an alternative for national parks that need to keep herd sizes in check and might otherwise have to kill some of the animals.

A buffalo resting in Custer State Park, SD, Sept. 2020. (Photo by Brianna Chappie)

ITBC, which represents 83 federally recognized tribes across 20 states, is one of many Native American groups that support the bill.

Carlson, the ITBC president, told senators that federal funding for buffalo management has been “minimal and stagnant,” which the Indian Buffalo Management Act would rectify.

“When you try to divide up $1.4 million among many tribes, it doesn’t go very far. Tribes need fencing, watering systems, genetic diversity in their herds, supplemental feed and testing that all require meaningful funds,” he said.

Reestablishing herds could also bring jobs to reservations and reduce food insecurity. Prices on reservations are high because of transportation costs. The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, which advocates for low-income Americans, says 1 in 4 Native Americans experience food insecurity.

Obesity and diabetes are also prevalent on reservations. According to data collected by the National Library of Medicine, 48% of Native Americans and Alaska Native adults are considered overweight, and the CDC says that Native Americans and Alaska Natives have a greater chance of having diabetes than any other racial group in the United States.

Buffalo meat is rich in protein, has less saturated fat and more micronutrients like vitamin B12, zinc, selenium and omega 3 fatty acids than beef.

“This legislation will advance food sovereignty and advance the protection and revitalization of cultural practices for tribes all across the United States,” Bryan Newland, assistant secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs, told senators.

At the same hearing, Heinrich recounted a visit to a tribe in New Mexico, the Picuris Pueblo. He said he was inspired by the way the members have been able to reincorporate bison into their diets and distribute meat within the community for free.

The senator called the resurgence of buffalo herds in the last few decades “a symbol of the enduring resilience of this iconic species, and a major economic development opportunity for many tribes.”

The bill would also help tribes with disease management.

Bison at Yellowstone Park, for example, have been prone to carrying brucellosis, a disease that has cost cattle ranchers billions. Bison are tested before being relocated.

“I hope that in my lifetime, thanks in large part to these tribal buffalo herds, we will see bison return to the prominent place that it once occupied, as a keystone species on America’s short grass prairies,” Heinrich said.

(Map courtesy of Buffalo Field Campaign)