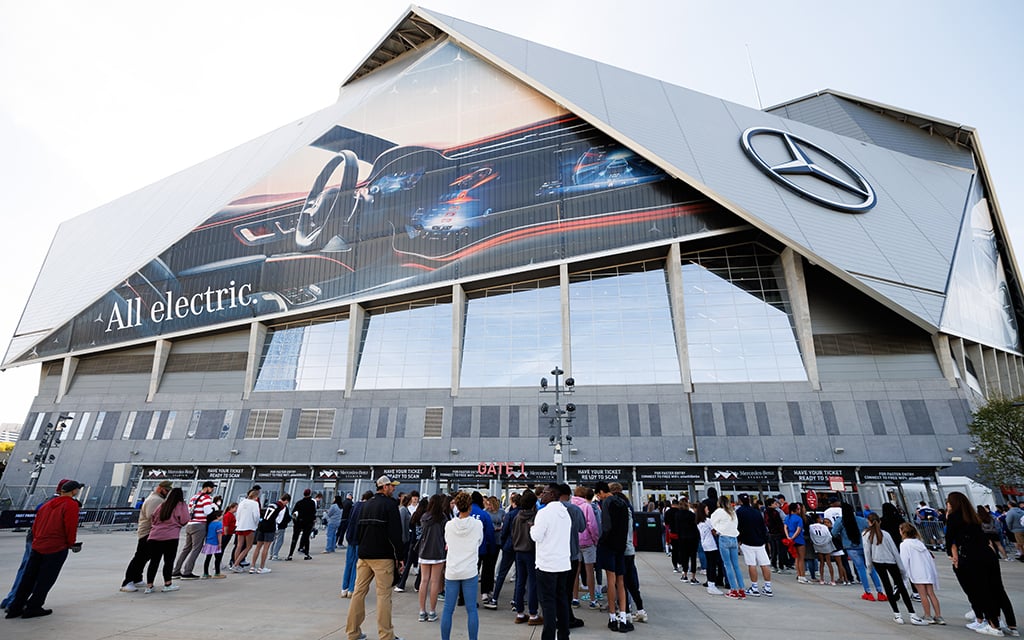

The solar panel installation at Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta generates 1.6 million kilowatt hours of renewable energy per year, reducing the venue’s electricity use by 29%. (Photo by Andrea Vilchez/ISI Photos/USSF/Getty Images for USSF)

PHOENIX – In the sports world, the word “green” is taking on a new meaning beyond just the color of uniforms or fields. As environmental concerns grow, the sports industry is going greener by embracing sustainable practices and technologies to reduce its massive carbon footprint.

Leading this charge are newer state-of-the-art venues designed with sustainability in mind. Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, Georgia, which opened in 2017, was the first to earn the highest (platinum) Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification by scoring 88 out of 110 points on the green building rating system.

LEED functions as a green building rating system that includes four distinct levels of certification – certified, silver, gold and platinum. To reach platinum certification, a venue must earn 80 out of 110 points on the LEED scorecard through innovative and sustainable building design.

Mercedes-Benz Stadium diverts over 90% of all waste. The stadium also features a unique solar panel design that generates 1.6 million kilowatt hours of renewable energy per year, reducing electricity use by 29%.

“I think it’s amazing for the Atlanta community to be able to come cheer on their favorite team while also seeing how you can build a green stadium and coexist with the environment,” said Dawn Brown, senior manager of stadium tours, education programs and sustainability at Mercedes-Benz Stadium. “We always want to educate the fans about what it means to do the right thing.”

However, Mercedes-Benz’s success in sustainability may not have come to fruition without the guidance of the Green Sports Alliance – a nonprofit organization established 14 years ago that works with teams and sports venues to help create sustainability within their operations and design developments.

“We are stronger together than we are alone, and we need to accelerate change as we know,” said Roger McClendon, executive director of the Green Sports Alliance. “It’s about sharing resources and leaving what we call playing for the next generation, leaving this world and earth a better place than where we found it.”

As an eco-friendly sports venue, Climate Pledge Arena utilizes recycled rainwater to create NHL-quality ice for home games of the Seattle Kraken. (Photo by Steph Chambers/Getty Images)

Climate Pledge Arena is another facility making the Green Sports Alliance proud since opening in 2021 as the home of the Seattle Kraken and Seattle Storm. The arena has quite literally made a name for itself from the very beginning.

“I want to give a huge thanks to the arena’s naming rights partner, Amazon,” said Kristen Fulmer, head of sustainability at Oak View Group. “The building could have been called Amazon Arena but was instead named after Amazon’s sustainability initiative, Climate Pledge.”

The arena is the first to achieve the International Living Future Institute’s Zero Carbon Certification by fully neutralizing its operational and embodied carbon emissions. Powered by 100% renewable energy with no natural gas, the arena cooks food using eclectic grills and uses recycled rainwater to make NHL ice for Kraken home games.

“They are trying to make sustainability fun,” Fulmer said. “They are doing a lot of things to engage fans, such as giving someone a public transportation pass for every event ticket they have.”

While new construction leads the way, older iconic venues are also stepping up their eco-efforts Kansas City’s GEHA Field at Arrowhead Stadium, which will host 2026 World Cup matches, is among the host stadiums refining its sustainability practices. While the 52-year-old stadium showcases strong practices, including a nearly 90% waste diversion and a community garden to provide food to the local food bank, it’s a new ball game for one of the largest sports tournaments in the world.

“With the World Cup coming to Arrowhead Stadium, FIFA is requiring the LEED Silver Certification,” said Brandon Hamilton, the vice president of stadium operations and facilities for the Kansas City Chiefs. “Our plan right now is to put out an RFP for an environmental consultant. Once we do that, our goal is to be prepared to meet the FIFA requirements by 2026.”

As GEHA Field at Arrowhead Stadium prepares to host 2026 FIFA World Cup matches, it is pursuing LEED Silver certification by implementing eco-friendly operations. (Photo by David Eulitt/Getty Images)

Even the motorsports industry, once considered a massive polluter, is cleaning up its act. NASCAR vehicles can emit around 120,000 pounds of carbon dioxide per race, while Formula One cars release nearly 256,000 tons of carbon dioxide per season.

While NASCAR and Formula 1 have no plans yet to ditch gas-powered cars, Formula E has pioneered all-electric racing.

In the meantime, F1 teams like McLaren are innovating with recycled carbon fiber materials that reduce environmental impact without compromising performance.

“We had a great example last year where data led us to look at what we need to do, and recycled carbon fiber is an amazing testbed for innovation,” said Kim Wilson, director of sustainability at McLaren Racing. “We pioneered that in the United States Grand Prix last year, and it’s been a really important proof point for us seeing that you can have more sustainable materials in your car that don’t have an impact on performance.”

NASCAR too is consulting multiple options with new sustainability initiatives, most recently at Talladega.

“We piloted a can collection system for the first time at this racetrack,” said Riley Nelson, head of sustainability at NASCAR. “It was a really successful first pilot for us and Talladega. It doesn’t make it a pain or something that detracts from the race experience but actually enhances the experience throughout the weekend.”

However, the road to sustainable sports is not without its speed bumps. The upfront costs of green construction and operations can be massive, with some critics questioning if higher ticket prices are worth it. There are also operational hurdles like securing adequate renewable energy sources and buy-in from fans accustomed to traditional event experiences.

Yet most experts insist the sports world must embrace sustainability not just for economic reasons, but for the very future of the games themselves which are threatened by climate change impacts like rising temperatures, drought, flooding and more.