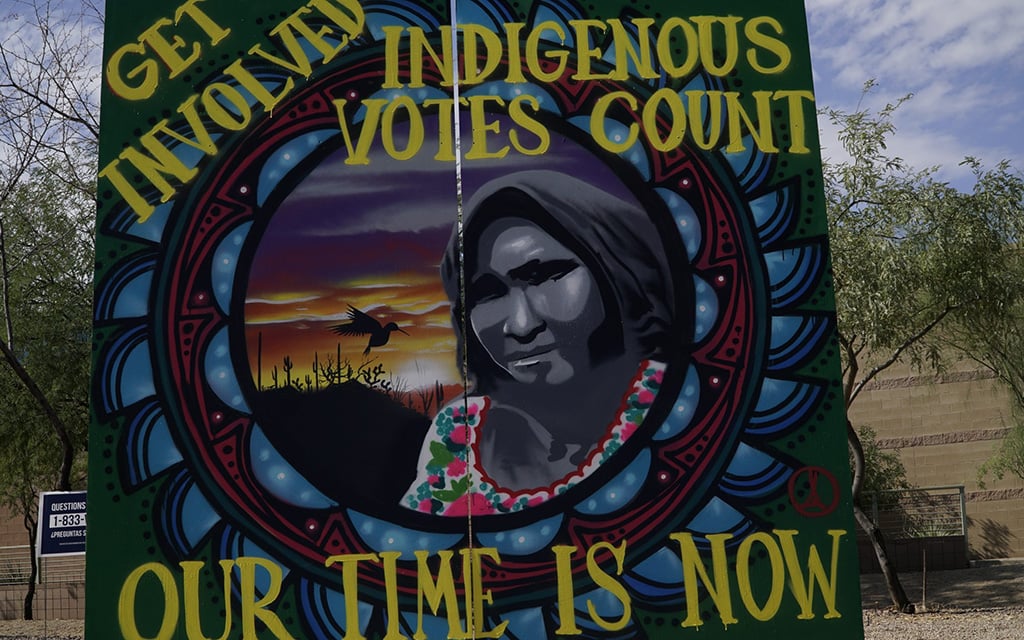

PHOENIX – As voters headed to the polls Tuesday to vote in the presidential preference election, Native Americans in Arizona continued to work within a system that has challenged their ability to vote for decades. With new legislation affecting the upcoming election in November, the challenge just got harder for Native Americans looking to exercise their voting rights.

In 2021, 19 states enacted 33 laws that target voting rights, which the Brennan Center For Justice characterized as restrictive legislation. Organizations around the country have been assisting people affected by these laws.

One of those pieces of legislation was Arizona’s HB 2023, which made the collection and delivery of another person’s ballot a felony. Some citizens of tribal nations who live in rural areas depend on ballot collection to cast votes because they cannot easily reach designated polling precincts. The Democratic National Committee challenged Arizona’s HB 2023 as violating the Voting Rights Act because it was enacted with discriminatory intent. The case of Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee went to the Supreme Court in 2021, which ruled that the Arizona bill did not violate Section 2 of the Voter Rights Act because there was no evidence of racial discrimination.

Organizations like the national nonprofit Native American Rights Fund provide legal assistance to tribal nations and focus on protecting voting rights.

Allison Neswood is an attorney working with NARF and a member of the Navajo Nation.

She said that NARF litigates cases across a broad range of Native American issues like tribal sovereignty, Native American rights and particularly voter-rights cases, on both state and federal levels.

“We litigate against involving statutes that might disproportionately deny Native Americans the right to vote. We work on vote-dilution issues. So during redistricting, if the district lines will dilute Native voting power, we litigate those issues,” Neswood said.

Neswood said compounding issues, such as distance from polls and unreliable transportation, affect voter engagement. Community organizations work to make the voting process easier.

“Native people care deeply about their communities and about lifting up their voice to make sure that our legislative officials are paying attention to our needs and our rights and our resources. But I think we’re also dealing with longstanding neglect,” Neswood said. “I think a lot of Native people can rightly feel discouraged.”

Community outreach is an important strategy

Arizona Native Vote, a Native-led nonprofit formed in 2023, raises voter awareness in tribal nations.

Jaynie Parrish, founder and executive director of ANV, is a member of the Navajo Nation and has been involved in political campaigning since 2011.

“We’re just always fighting for Native vote efforts ever since we were granted the right to vote,” Parrish said. The Indian Citizenship Act granted Native Americans citizenship and the right to vote in 1924. “It’s about increasing civic engagement, increasing turnout – increasing the voices of Native people in our community.”

Parrish said that ANV has three experienced organizers in both the Navajo Nation and the Hopi Tribe.

“They’ve been doing this work for years, meaning they’ve been helping people register to vote, they’ve been advocates of Native American voting rights and really trying to get their families informed about what that means,” Parrish said, emphasizing that their organizers will often do community services like delivering wood or water and providing information on local government meetings.

“The beauty of that part is they’re able to establish relationships in the community beyond just voting in elections,” Parrish said.

The organization’s plans include contacting 50,000 potential voters, advocating for early voting and increasing Native American voter registration and turnout this year by 2%.

To connect with young people, the organization also teaches democracy classes to teens in the Navajo Nation.

“It’s a way to start getting younger voters involved at an earlier age,” Parrish said. She added that ANV wants interested students to train and work with the organization during their senior year of high school and through college.

Parrish said one hurdle facing ANV activists is the time and travel commitments to cover Native lands. The Navajo Nation, for instance, covers 27,425 square miles and straddles three states.

Another problem is that many Indigenous residents don’t have standard street addresses but instead rely on post office boxes, which have not been recognized as formal addresses when registering to vote. A federal court in September rejected part of an Arizona law and said the state could not require a street address for voter registration, if the voter could present documents with a P.O. box or tribal documentation.

Parrish said the differences between counties and their different registration periods can prove challenging for new voters. A lack of stable internet access or phone services is also an issue, and these problems combined make understanding the voting process time-consuming.

Parrish said for older generations, printed documents and tribal radio broadcasts are still the primary form of spreading information.

Neswood believes that the community-led approach to addressing voting rights works well alongside NARF’s work on the legal end. While she’d like to see sweeping legislative changes, progress made so far should help voters later this year.

“I think continued efforts on all fronts – from litigation to policy to coalition building with those local organizations that are on the ground and helping mobilize and helping them protect their community’s rights – it’s just all in play right now,” Neswood said.