PHOENIX – A national oral history project aims to document the experiences of Indigenous children who attended federal boarding schools. The Department of the Interior announced the project in September as part of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) has been entrusted to lead the project with $3.7 million in grant funding through the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

“NABS is an organization that does this work already and approaches the interviewing in a healing-centered approach to really care for our relatives and the survivors of Indian boarding schools,” Melissa Powless, senior director of the NABS oral history project, said. “Healing is a large part of the intent and efforts.”

The project is designed to take place over two years, and the grant will provide for resources and staffing, according to Powless.

Arizona ranks second in the country for the number of boarding schools that have operated in the state – 59, behind Oklahoma’s 95 – according to recent research from NABS.

With 22 federally recognized tribes in Arizona, there has already been an effort across the state to collect data, artifacts and stories from boarding schools for research and education.

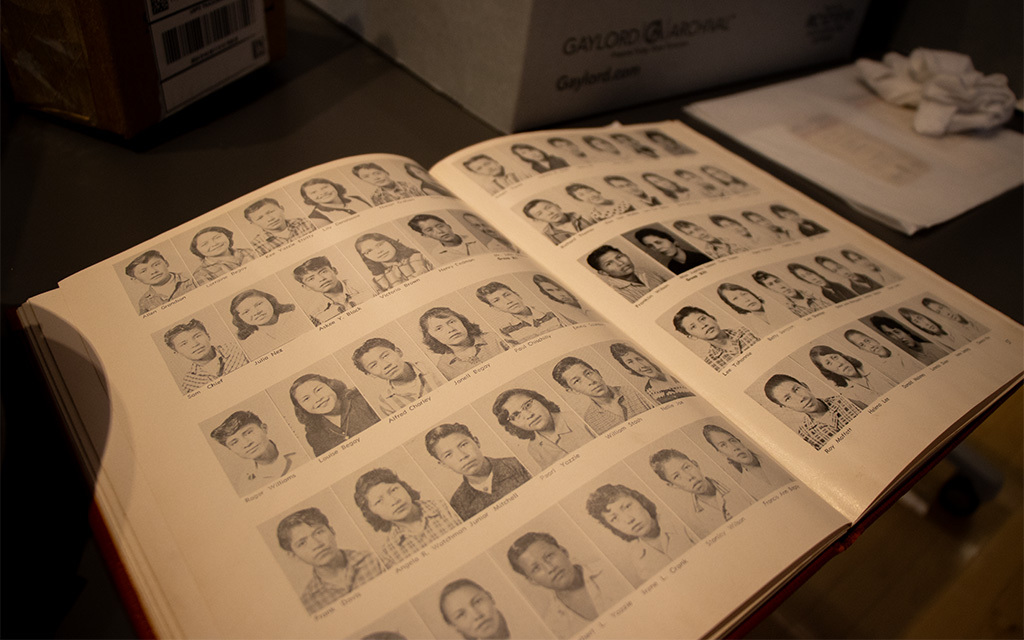

A yearbook with the faces of those who attended Phoenix Indian School in the 1950s in the archives at the visitor center at the old Phoenix Indian School building. (Photo by Ellie Willard/Cronkite News)

A history of boarding schools

Spanish missionaries began arriving in what is now the southwestern United States in the 16th century, aiming to convert the Indigenous people to Catholicism.

The Civilization Fund Act of 1819 authorized funding for organizations to run schools on Indigenous land as an effort to assimilate Indigenous people into European-American religious beliefs and cultural norms.

In 1879 in Pennsylvania, the first government-run boarding school, Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was opened by Lt. Col. Richard Henry Pratt, whose common refrain, according to historical accounts, was: “Kill the Indian, save the man.”

More boarding schools followed suit.

Separating children from their families and cultural traditions was a way the U.S. government attempted to reprogram Indigenous children and further the systematic destruction of Indigenous communities.

Due to a lack of formal recordkeeping, there is no concrete number of how many boarding schools were in operation nationwide, but NABS estimates there have been 523 in operation from 1801 to today.

“The assimilation that took place was under a lot of direct control and abuse,” Powless said.

Constructed between 1900 and 1901, the dining hall is the oldest surviving Phoenix Indian School building at what is now Steele Indian School Park. In its early days, it served as an agricultural building where student-raised livestock was prepared as food, but lower costs eventually led to students being served highly processed food instead. The building has remained vacant since the school’s closure in 1990. (Photo by Ellie Willard/Cronkite News)

Early boarding schools imitated military life. Upon entry, children’s hair was cut short, their tribal clothing stripped in favor of uniforms and new names were assigned to them by the government, according to a 2022 Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report.

Indigenous children were punished for speaking their native languages and were compelled to replace their traditional religious practices with Christianity.

Curriculum and school life evolved from agriculture, labor and vocational education to more academic coursework, reform and college preparation in the later years. Cultural programming generally was limited until the 1960s, when many tribes began to oversee the schools.

“Boarding school is a very personal experience,” said Patty Talahongva, who attended Phoenix Indian School from 1978 to 1979. “What happened to me is very different than what happened even to my sister who went to boarding school with me.”

Phoenix Indian School, originally Phoenix Industrial School, opened as a Bureau of Indian Affairs-run boarding school in 1891 at the corner of what is now Central Avenue and Indian School Road. It officially closed in 1990, but three school buildings were placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In June 2021, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland announced that the U.S. government would investigate its oversight of boarding schools and focus on the intergenerational impact through the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

The uprooting of children and attempted erasure of Indigenous culture and practices has led to multigenerational trauma and in some cases a loss of identity or heritage within family lines. And that trauma is at the root of the current social health and economic disparities that Indigenous people face, Powless said.

“I never thought of myself as a boarding school survivor until I started thinking about, ‘It’s not just me, it’s my mom and dad, my grandparents, and all the family,’” Talahongva said. “We are survivors, and we’ll keep talking now because it’s high time people know this history.”

Inside the Memorial Hall building at Steele Indian School Park is a theater that served the Phoenix Indian School. The building has been maintained and can be rented out by the public. (Photo by Ellie Willard/Cronkite News)

A local push for preservation

In the mid-1990s, a former associate curator of the Heard Museum, Margaret Archuleta, began research into the history of Native American boarding schools.

After receiving funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Heard Museum opened the exhibit “Remembering Our Indian School Days: The Boarding School Experience” in 2000. It has become one of the museum’s most popular presentations and stands as one of the only in the country dedicated to sharing the full reality of the boarding school experience and expanding research.

The exhibit was only planned to run for about five years, but the overwhelming positive public response – and surprise at how little the general public knew about the topic – encouraged the Heard staff to keep the exhibit and eventually do an update, said Janet Cantley, curator and project manager of the exhibit.

That updated exhibit, “Away From Home: American Indian Boarding School Stories,” opened in 2019 and could not have been as thorough as it was without a six-person advisory committee overseeing content and helping with data collection, according to Cantley.

“In the exhibit, you’re going to see many videos … some of them are interviews from alumni and myself included,” said Talahongva, who served on the advisory committee. “It’s really important to get as many oral histories as possible from the students who went to the schools.”

The exhibit delves into the history of Native American boarding schools while tying in images, music, sound, oral interviews and videos of firsthand records to encapsulate the experiences of those who lived them.

That information was collected by conducting interviews, asking for donations from alumni and utilizing still-standing former school grounds such as the Phoenix Indian School for firsthand data and information to build upon the historical record.

The Phoenix Indian School now functions as a visitor center with scheduled tours of the building. In its collection, there is student work, yearbooks, newspaper articles, personal belongings and firsthand accounts, mostly donated by former students.

“Some things were left here and then some things are slowly, gradually coming back to Phoenix Indian school itself,” Elena Selestewa, visitors center specialist at Native American Connections, said.

Those archives serve as a guide to understanding what school looked and felt like for students while in session. They contribute to the growing digital archive that Phoenix Indian School and Native American Connections are working toward, and they served as a collection resource for the Heard Museum.

The people behind these existing databases and archives hope their work can help guide new research efforts like the national NABS project.

Both the Heard Museum and Phoenix Indian School hold records from those who did not directly attend the school, including administrators, teachers and offsite labor records, which have added another element to their research. NABS’s oral history project is focused on interviewing just survivors.

Oral history can serve as an important tool for displaying and understanding individual experiences of boarding school and can showcase how it has affected whole families.

Elena Selestewa, a visitors center specialist at Native American Connections and Phoenix Indian School, reads through a photo book of historical records and experiences from Phoenix Indian School. (Photo by Ellie Willard/Cronkite News)

“It’s important to document what happened to individual people at boarding school because even the ones who, I would say, had it really hard, they’re gone,” Talahongva said. “It’s important to expose what the government did and to make people more aware of how quickly something so horrendous can become normalized.”

From a quilt illustrating the painful account and journey of a woman’s family members who attended boarding schools on the Navajo Reservation, to stories of men who graduated boarding schools and had no other choice but to join the military because they didn’t know where home was, the Heard Museum’s exhibit acknowledges those experiences of intergenerational trauma.

Selestewa had no idea her family had a boarding school association until she began working at Native American Connections. She discovered her grandmother attended Phoenix Indian School, which made her feel as if she didn’t know herself because she lacked knowledge on the true history of her family line.

“It sent me into the motion of understanding intergenerational trauma at the genetic level. That’s why we have high numbers of suicide … substance abuse, alcohol abuse, domestic violence, diabetes,” Selestewa said. “It really does go back to what stems from the boarding school.”

Now, Selestewa begins her Phoenix Indian School tours by introducing herself in Hopi to reclaim, acknowledge and continue the legacy of her native language and heritage.