Winter is off to a dry start across the West, with wide swaths of the Rocky Mountains seeing lower-than-average snow totals for this time of year. But scientists say there’s still plenty of time to end the “snow drought” and close the gap.

High-altitude snowpack has big implications for the region’s water supply, which serves about 40 million people across seven Western states. Two-thirds of the Colorado River’s water starts as snow in Colorado’s mountains before melting and flowing into the watershed.

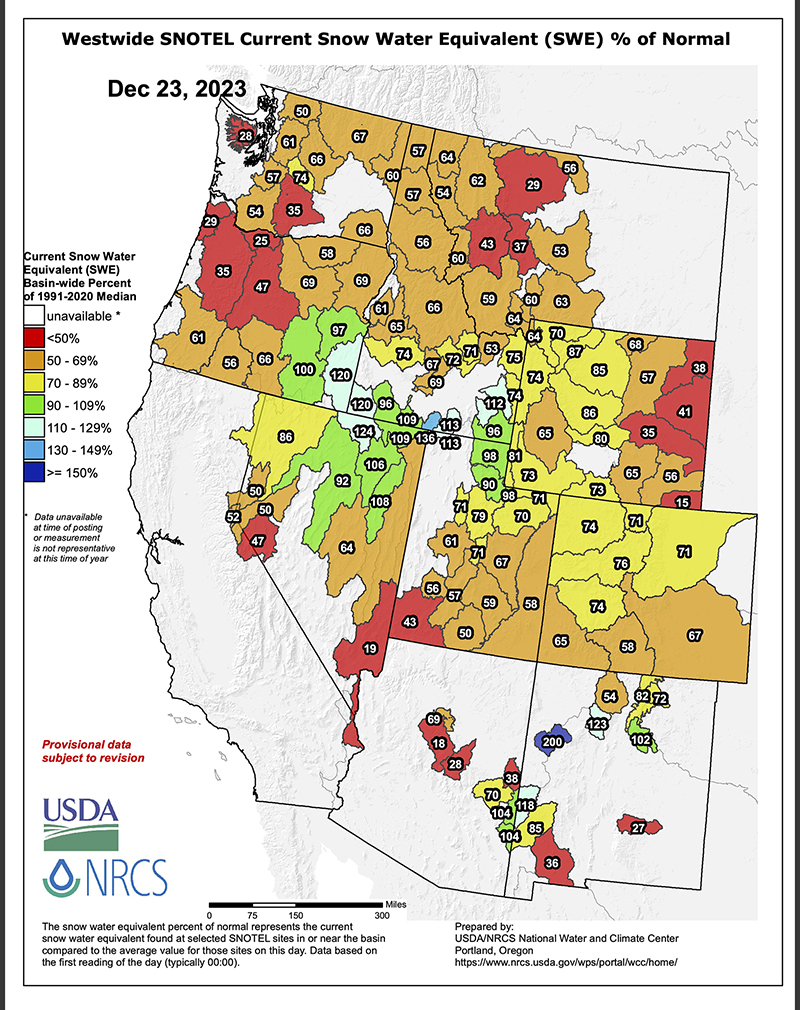

Nearly every part of Colorado, Utah and Wyoming had significantly less snow than usual for late December, according to data last week from a region-wide network of snow sensors. They showed many areas with snow totals around 60% or 70% of normal.

“It’s really going to be dependent on what we see in January and February,” said Becky Bolinger, Colorado’s assistant state climatologist. “We’re really going to need an active January and February to make up these deficits and be OK.”

But even a few consecutive wet winters would not be enough to seriously fix the the West’s water crisis. More than 20 years of dry conditions, fueled by climate change, have shrunk the Colorado River’s water supply, and policymakers have been unable to agree on significant, long-term cutbacks to water use.

This map shows snow totals as a percent of normal, and nearly every part of the Colorado River Basin had below-average snowpack data as of the Dec. 23 report. (Map courtesy U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service)

Last year, big snows in the Rockies helped boost the Colorado River’s major reservoirs. Policymakers said that snowy winter took some pressure off their tense negotiations about sharing the river’s water in the future.

Experts say it would take five or six consecutive above-average winters to close the gap between the region’s dwindling water supply and rising demand. They say that level of precipitation is unlikely to happen as climate change makes the region warmer and drier.

Dan McEvoy, regional climatologist at the Western Regional Climate Center and Desert Research Institute, said last year’s wet winter was an “anomaly.”

“Lots of data, lots of research, projections, modeling, all point to this continuing trend of warmer winters, less snow and in some cases, less precipitation,” he said.

Last year’s snowy conditions did deliver one major positive for the Colorado River — soaking the soil and helping this year’s snowmelt run off to reach the streams, rivers and reservoirs. Dry soil acts like a sponge and soaks up runoff. After a high-snow winter, the soggy soil should help a higher percentage of the next year’s snowfall reach waterways.

Despite the low snow, ski resorts may not be feeling much financial pain. Chad Dyer, managing director of ski website OnTheSnow, said a lot of ski traffic around the holidays came from tourists who cemented their plans in advance.

“Their flights are booked, their lodging is booked. As long as the ski resort is open and has got a product, by and large, they’re going to visit,” Dyer said.

Dyer also pointed to statistics from a recent Vail Resorts earnings call. The mountain ownership company said it expects 73% of its worldwide skier visits come from season passholders. That high volume of pre-purchased lift tickets lets ski resorts depend less on ticket sales that may ebb and flow with the quality of ski conditions.

The next few weeks are unlikely to bring much immediate relief for Western mountains.

“The medium- to long-range forecasts that go out about two weeks are not super promising,” McEvoy said. “There are some signs of some smaller storms that can impact parts of the West. But overall, it’s a pretty dry forecast.”

-This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported by the Walton Family Foundation.