PHOENIX – The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is proposing that a snail found only in Arizona be listed as an endangered species after effects of drought and border wall construction have reduced populations.

The Quitobaquito tryonia, native to the state, is a freshwater snail that lives in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, over 100 miles west of Tucson.

The agency is asking to designate a 6,095-square-foot plot of land, which includes a concrete channel leading to a pond, as a critical habitat for the species.

Historically, the snail has populated three springs in the state. Drought and climate change, however, have eradicated the population in two of the springs.

The agency has determined the snail is at risk of extinction, citing drought and groundwater pumping from construction of the U.S.-Mexico border wall.

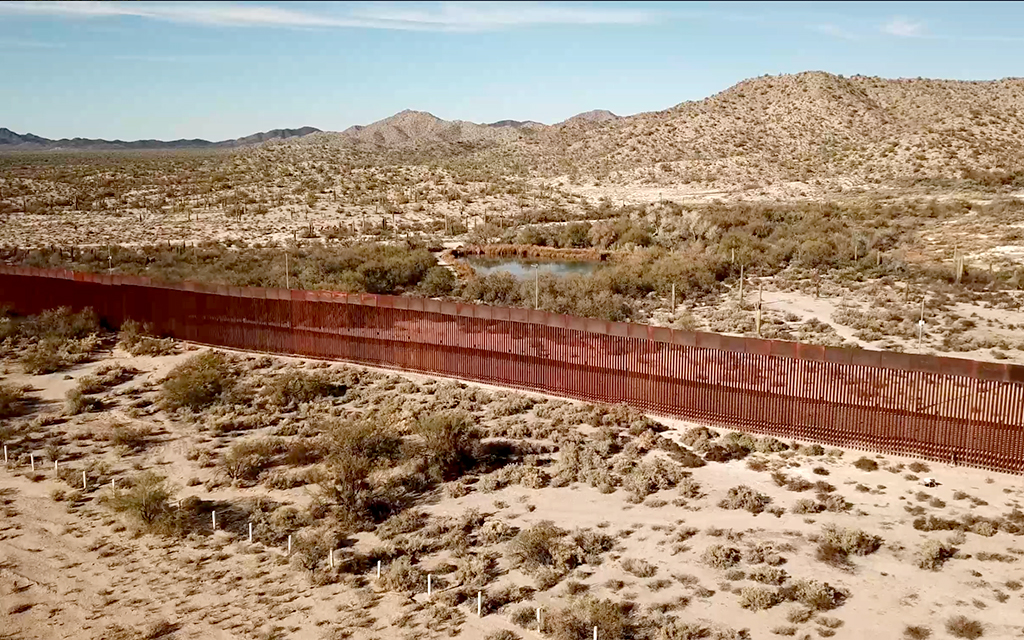

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has determined the Quitobaquito snail is at risk of extinction, citing drought and groundwater pumping from construction of the U.S.-Mexico border wall, which is within viewing distance of the pond. (Photo courtesy of Center for Biological Diversity)

“We have been watching groundwater tables around the region fall, and that means animals like the Quitobaquito snail and the other wildlife that depend on this spring are made even more vulnerable by the drought,” said Laiken Jordahl, Southwest conservation advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity.

The rare Quitobaquito is typically colored gray, black or clear. It feeds off algae, fungi, bacteria and organic material, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service posting.

The snail is small – typically just 0.05 to 0.08 inches in length – about the size of a chia seed.

Because the Quitobaquito snail is not a migratory species, once it finds a feasible habitat, it is unlikely to relocate to another one.

“This is all set to the backdrop of climate change and increased water pumping, water usage around the West,” Jordahl said. “So it’s really a coalescence of a number of significant threats that are pushing this species closer to extinction.”

If listed as endangered, the Quitobaquito snail would be the 22nd species to be listed as endangered or threatened by the federal government in 2023. That is the most since 2016, when 73 species were listed.

“Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument is critical to the Quitobaquito tryonia because the species is only found within the Monument. That we are aware, it occurs nowhere else in the world,” the U.S. Fish and Wildlife said in a statement, noting drought is a critical factor in the changing habitat. “Climate change is expected to further exacerbate drought conditions.”

Dry conditions can reduce oxygen levels and raise temperatures in bodies of water, as well as concentrate water pollutants.

If there is a lack of water flow, aquatic life can suffer from reduced water quality.

Pima County, which is the only place in the world where the snail is found, recorded its 14th-driest July on record, according to the National Integrated Drought Information System.

The January to July period was also the 38th driest in the last 129 years. The county received 1.37 fewer inches of precipitation than the average.

“Its entire survival depends on the perennial flow of water to Quitobaquito Spring,” Jordahl said of the snail. “If that water dries up, it’s pretty simple: That spells extinction for this tiny and vulnerable creature.”

The snail lives in a 700-foot human-made concrete channel of Quitobaquito Springs. The National Park Service constructed the channel in 1989 to create a bevy of habitats available to local wildlife.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife said in a news release destruction of water habitats likely started as far back as the 1860s, when ranchers built a dam. Wildlife advocates say the existing problems were worsened by the building of the border wall.

“Just a couple of years ago, Border Patrol was pumping out millions of gallons of groundwater from the aquifers that feed Quitobaquito and that meant that it made the spring water more and more vulnerable,” Jordahl said. “We’re extremely concerned about any future attempts to further militarize or build additional border walls, and that certainly is a real threat when it comes to the species.”

If the pond were to be designated as a critical habitat, it would create a site for reproduction and overall population growth, and it would introduce protections to prevent destruction of the area.

If the Quitobaquito snail were listed as endangered, it would join a federal list of animals, plants and other wildlife that are afforded protections from being killed, harmed or otherwise uprooted from their habitats.

“The Endangered Species Act is the single best tool that we have to protect vulnerable wildlife,” Jordahl said. “By listing the species, it will enable additional levels of consultation with Fish and Wildlife experts and, ultimately, hope to mitigate future threats that face this really special snail.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is seeking public comment over the next 60 days on the proposal to list the Quitobaquito as an endangered species.