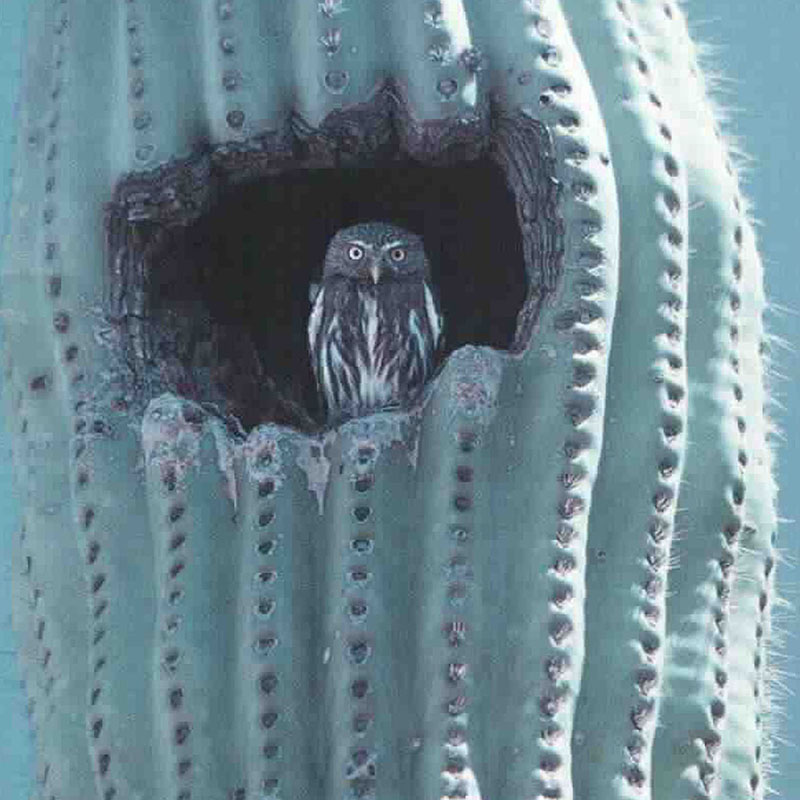

Cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl numbers had fallen to 35 birds in Arizona when it was declared endangered in 1997, a designation that was later overturned in a lawsuit. Arizona now has several hundred of the birds, which were granted threatened status this week. (Photo by Rachel Laura/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

WASHINGTON – Federal officials this week granted threatened species status to the cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl, capping 17 years of “litigation and controversy” from advocates fighting to win protection for the 6-inch raptor.

The bird, found in southern Arizona, southern Texas and northern Sonora, Mexico, has already disappeared from parts of Arizona, where the population is believed to be in the low hundreds. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service granted threatened status, saying the owl is “likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future,” as it faces threats from development, invasive species, climate change and more.

“It’s just taken us an immense amount of effort to get protection back for a species that everybody agrees is in trouble, in particular in the Sonoran Desert,” said Noah Greenwald, endangered species director at the Center for Biological Diversity.

It’s the latest turn for the pygmy-owl, which won endangered status in 1997, lost it in 2006 and which conservation groups spent another 17 years fighting to restore.

Unlike the previous endangered status, which applied only to the owls in Arizona, the threatened status applies to birds all through its range. This week’s announcement did not include a designation of critical habitat for the protection of the bird, but a decision on that is expected within a year.

“This little owl, as small as it is, has caused a lot of excitement and controversy,” said Scott Richardson, a USFWS supervisory biologist in Arizona.

The cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl is descriptively named: rust-colored, and tiny, it often lives in the hollows of cacti in the Sonoran Desert. Although only 6 inches tall, it is aggressive for its size, sometimes preying on birds twice its size.

But it is a “second-nester,” meaning it will only nest in tree and cactus cavities abandoned by other birds. Their nesting sites have been limited by the expansion of invasive buffelgrass, which sparks wildfires that can destroy cacti and make it difficult for the owls to find food.

The bird also faces threats to its habitat from climate change and development, according to the Endangered Species Act listing posted in Thursday’s Federal Register.

“We’re really seeing the Sonoran Desert unraveling in front of our eyes, with the spread of things like buffelgrass that promotes fire and threatens the existence of saguaros,” Greenwald said. “With climate change on top of that, it’s very concerning. If we can save the pygmy-owl we’ve saved the Sonoran Desert.”

In 1997, there were just 35 pygmy-owls in Arizona, which led the service to declare it endangered as a distinct population segment – which allowed the status to be declared only in Arizona.

The National Association of Homebuilders in Arizona sued in 2001, arguing the Arizona population was not sufficiently distinct from the others and was not critical to survival of the species, which had a presence in Texas and Mexico. Endangered status was not merited, the homebuilders argued, and a court agreed.

The cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl gets part of its name for its habit of nesting in cavities of cacti. (Photo by Tom Gatz/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

“Ultimately, the courts found that we did not show that the species was significant, or that the distinct population segment was insignificant to the rest of the species,” Richardson said, “So they kicked it back to us and said, ‘Try again.'”

The government ended the owl’s endangered protection in 2006. A year later conservation groups, including the Center for Biological Diversity and the Defenders of Wildlife, petitioned to have the pygmy-owl’s endangered status restored.

The service rejected the petition in 2011, sparking legal action by the conservation groups. Among their charges was a claim that the government was taking too long to make a decision – a problem that Greenwald said exists to this day.

“It took us 17 years to get protections back even though it was clear that it needed protection this entire time, there was never any question,” he said. “That just reflects that the Fish and Wildlife Service just let politics into their decisions too often.”

Richardson said conservation groups are “entitled to think what they like,” but that the service’s “intent is not to delay or drag anything out.”

“We do the best we can with the resources we have and the time given our workload,” he said.

The service in December 2021 proposed that the owl be listed, this time as threatened throughout its range, a decision that was finalized with this week’s announcement.

The government must still designate critical habitat – the areas essential to the conservation of the owls. But the Arizona Game and Fish Department said it is “opposed to any designation of critical habitat,” citing the increase in “regulatory burden for private landowners.”

Richardson said the service believes listing is the best move for the conservation and recovery of the pygmy-owl but, noting the history of legal sparring, that status could be challenged at any time.

“We get pressure on almost all species we list,” he said. “We get pressure from the environmental side that thinks we aren’t going far enough and we get pressure from industry and the other sides who say we’re going too far and regulate things too much,”

Greenwald said he is glad the pygmy-owl is protected again, but that the service “needs new leadership and reform” to effectively combat what he called an “extinction crisis.”

“If we lose the pygmy-owl we’ve really lost the Sonoran Desert because it’s just a great indicator of healthy Sonoran Desert, it relies on soil and cactuses for nesting and secondary cavity nesters,” Greenwald said.