WILLCOX – Chiricahua National Monument – one of Arizona’s unique sky islands with a history that includes Geronimo, Buffalo Soldiers and the 1930s Civilian Conservation Corps – could become Arizona’s fourth national park if a bipartisan bill finally passes this year in Congress.

And that could mean more tourism and resources for communities near the Chiricahua Mountains monument, known for its biodiversity and rock spires towering out of the southeastern Arizona desert.

“It could definitely have a positive effect on the local communities that are nearby,” said Julie Blanchard, supervisory park ranger for the National Park Service in southeast Arizona. Because Chiricahua has limited campgrounds and no concession amenities, more visitors would mean a need for more lodging and restaurants, she said.

Arizona currently has three national parks – Grand Canyon, Petrified Forest and Saguaro – and 13 national monuments. In March, U.S. Sen. Mark Kelly, D-Ariz., reintroduced for the second time the Chiricahua National Parks Act – a bill to make Chiricahua National Monument a national park.

The Senate bill is co-sponsored by Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, I-Ariz. A companion bill was introduced in the House by Rep. Juan Ciscomani, R-Tucson, who called the legislation “long overdue.”

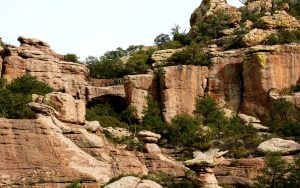

This small natural bridge is at the end of the Natural Bridge Trail. Bridges are formed by water running underneath, and arches are formed by wind erosion. (Photo courtesy of National Park Service)

“Our bipartisan legislation to designate Chiricahua National Monument as a national park would further promote conservation, boost tourism, and create economic opportunities in Southern Arizona,” Kelly said in a March statement. A similar bill passed the Senate in 2022, but failed to get a vote in the House.

In the same March statement, Sinema echoed Kelly: “Adding Chiricahua National Monument as Arizona’s fourth national park will boost tourism, create jobs, and fuel opportunity in Cochise County,” she said.

Of the nation’s 63 national parks, 27 drew more than a million people annually, and another dozen attracted at least 500,000, according to 2022 NPS totals. Chiricahua National Monument had 61,377 visitors in 2022, while the Grand Canyon saw 4.7 million visitors last year, according to NPS.

If Chiricahua does become a national park, not much will change quickly, according to rangers. The new designation would not mean an automatic budget increase, for example, said NPS’s Blanchard. If visitation grows, it could mean more upkeep on existing trails and campsites.

“As far as land mass and recreational opportunities, there’s nothing that will change there,” Blanchard said. “The footprint of the park isn’t going to get larger. We won’t acquire more land.”

Willcox – the nearest town, about 36 miles northwest of Chiricahua – has been lobbying for the park designation. Amber Bowlby, administrative assistant for the city’s development services, public works and streets departments, said via email the city believes it will get more visitors as a gateway to a national park, which will “have a positive impact on our community and local businesses.”

Chiricahua Park Ranger Suzanne Moody said if the park does get more funding eventually, it could hire more staff and work on infrastructure, such as parking lots.

In contrast to national parks, monuments have very little developed visitor and recreation infrastructure, according to the journal Science Advance. A national park designation also generally means more exposure from travel guides, documentaries and even picture books that chronicle the grandeur of America’s parks.

That could bring greater awareness of Chiricahua’s unique history and landscape, which the Apache called “The Land of Standing-Up Rocks.” A literal stomping grounds of Geronimo, Chiricahua’s Camp Bonita was home to an all-Black Army unit of Buffalo Soldiers, sent in the late 1880s in part to capture the Apache leader.

President Calvin Coolidge named Chiricahua a national monument on April 18, 1924, calling it a “wonderland of rocks.” Monument status protected the area’s unique hoodoos and balancing rocks and onsite Faraway Ranch once owned by Swedish immigrants. The Great Depression brought more attention, when a CCC camp was constructed at Chiricahua’s Bonita Canyon in 1934.

In one of the largest peacetime mobilizations, the CCC deployed 250,000 young men to work camps throughout U.S. public lands in an effort to put people back to work protecting resources, providing recreational areas and constructing rural infrastructure. Men of the CCC built trails, buildings and signage still used today at dozens of Arizona sites, including Colossal Cave Mountain Park, South Mountain Park and Petrified Forest National Park.

Rhyolite Canyon Tuff at Chiricahua National Monument is a volcanic rock formed from a volcanic eruption 27 million years ago. (Photo courtesy of National Park Service)

“It’s got a very special aura to it in a way, or a sense of connection to people that might be difficult to find in other places,” Moody said. “The people probably come to Chiricahua because of the landscape. Most of us don’t realize southern Arizona is not all sand and cactuses.

“Chiricahua seems to have a strong pull on visitors and local people as well,” Moody added. “It’s coming up a mountain range that has real oak and pine trees when people are expecting maybe all desert areas, so it’s much cooler, and it snows in the winter most years.”

Several well-known national parks – from the Grand Canyon to Joshua Tree, Zion, and Olympic – started as national monuments. New Mexico’s White Sands became a national park in 2019. Recreation visits at White Sands National Park grew from 608,785 in 2019 to 705,127 last year.

Monuments do not always see big changes in visitors when they become national parks, however. Saguaro National Park, a national monument in Arizona until 1994, did not see a gain in visitors in 12 years following its designation as a national park. In 1994, the park had 768,685 visitors. Saguaro finally saw an increase in visitors to 820,426 in 2016 and topped 1 million in 2019; 908,194 people visited the park in 2022, according to NPS data.

Spending in communities near national parks does grow as visitors do. In 2021, 297 million park visitors spent an estimated $20.5 billion in local gateway regions while visiting National Park Service lands across the country, according to the 2021 National Park Visitor Spending Effects report. In Arizona that year, more than 10 million visitors spent an estimated $1.1 billion in local gateway regions visiting National Park Service lands.

In 2021, visitors to Saguaro National Park alone spent $77.4 million in gateway communities, including $26.2 million on lodging and $15.2 million at restaurants, according to NPS. That year, visitors to Chiricahua National Monument spent a total of only $3.5 million, including $1 million on lodging and $650,000 at restaurants.

Chiricahua is believed to have formed after a volcanic eruption 27 millions years ago left 2,000-foot-high layers of pumice and ash that fused to create rhyolitic tuff rock, which weathered into a maze of columns rising from the desert floor. The area is called a sky island because it is one of the isolated mountain ranges in southeastern Arizona and northern Mexico that rise more than 6,000 feet above the surrounding desert, creating a range of biodiversity that is unusual for the region.

The area is home to unique animals such as the Mexican jay, which only has a sliver of territory in the United States. And in 2021 Chiricahua was added to the Tucson-based International Dark-Sky Association’s list of parks “possessing an exceptional or distinguished quality of starry nights and a nocturnal environment that is specifically protected for its scientific, natural, educational, cultural heritage, and/or public enjoyment.”

“Chiricahua National Monument has long been a beloved landmark in Southern Arizona,” Ciscomani said in a March statement. “These unique formations draw visitors from across the nation and around the world to our state, and this tourism is an important part of our regional economy. With this legislation, the Chiricahuas will finally receive the designation they deserve. It is long overdue.”