PHOENIX – For generations, Indigenous people have suffered the loss of missing and murdered loved ones, an issue that is difficult to solve given incomplete data and a lack of collaboration among tribal and governmental entities.

Murder is the third-leading cause of death among American Indian and Alaska Native women, according to a 2018 Urban Indian Health Institute report. And the report said Tucson was one of the cities with the highest number of cases of missing and murdered women and girls.

Violence against Indigenous people exceeds national averages, and according to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, “Community advocates describe the crisis as a legacy of generations of government policies of forced removal, land seizures and violence inflicted on Native peoples.”

In an effort to make progress on solving this issue, Gov. Katie Hobbs in March created an Arizona Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Task Force.

Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes discussed the issues of missing and murdered Indigenous people at her office in Phoenix on March 21, 2023. (Photo courtesy of Arizona Attorney General’s Office)

Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes, who is on the task force, said over the past few decades, Arizona has seen a dramatic uptick in the number of missing and murdered Indigenous people.

“You have multiple jurisdictions who have authority to act on crime on tribal lands: the federal government, the state government, sometimes tribal courts and tribal police,” Mayes said, noting it will take collaboration to solve the issue.

Because of the jurisdictional issues, it is not uncommon for cases to get lost in the system, Mayes said. “We need to shine a bright light on this problem, so these cases get solved and these women and these people do not get forgotten,” she said.

Capt. Paul Etnire with the Arizona Department of Public Safety is also on the task force. He agreed that the jurisdictional issue is one of the many challenges blocking a solution. However, he believes this is a 500-year-old issue that is now becoming more noticeable because of new technology like social media.

“It is kind of disheartening if you look at it, just the injustice within Indian Country, the inequities of justice being applied,” Etnire said.

Etnire, who is Hopi and grew up on the Hopi Reservation, said it was not uncommon there to not know where someone was.

“It wasn’t uncommon to say, ‘Where’s this person at, or they’re lost, and they’ll come back, they’ll show up a month or two weeks from now,’” Etnire said. The expectation from family members that the missing person would show back up caused reluctance to involve police, he said.

Etnire said the way to help is by getting more hands involved, and that’s what the Arizona Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Task Force intends to do through collaboration.

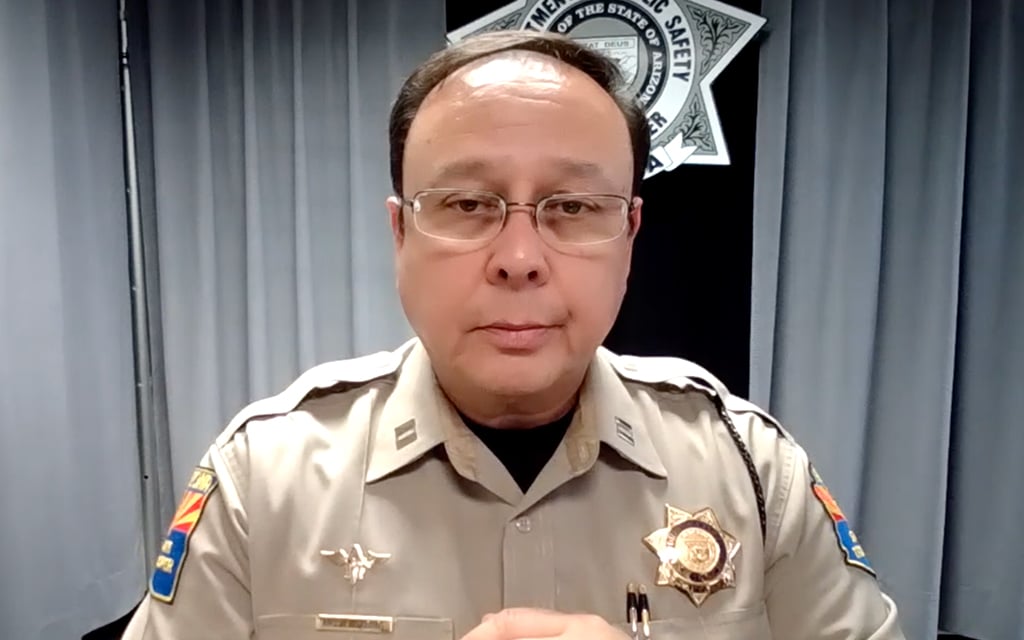

Arizona Department of Public Safety Capt. Paul Etnire is part of Arizona’s newly formed Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Task Force. He speaks about the issue via video on March 28, 2023. (Video screengrab by Alexia Stanbridge/Cronkite News)

Arizona is not the first state to implement such a task force – other states include Washington.

The Washington State Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People Task Force began meeting over a year ago and has found some success, said Annie Forsman-Adams, a policy analyst for the Washington State Attorney General’s Office who is on the task force.

Last year, Washington established the first missing Indigenous person’s alert system in the nation, Forsman-Adams said. The alert system, which functions similar to Amber Alerts sent to people’s phones, has been activated “dozens of times now.”

“I think we’ve had close to 40 reports, and we have found people, we have found people that maybe may not have been found,” Forsman-Adams said.

The Urban Indian Health Institute report said that while there were 5,712 reports of missing Indigenous women and girls to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center in 2016, just 116 of those cases were reported in NamUs, the Justice Department’s National Missing and Unidentified Persons System. The institute decided to focus its study on cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in urban areas in an attempt to find out “why obtaining data on this violence is so difficult” and how police and media are handling the issue.

The institute report identified 506 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in urban areas between 1943 and 2018, but noted that number is “likely an undercount.”

Annie Forsman-Adams is part of the Washington State Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People Task Force. (Video screengrab courtesy of TVW)

Of 71 cities surveyed by the institute, Seattle had the highest recorded number of cases in the nation, with 45; Tucson was fourth with 31 cases. The report said of the 29 states where data was collected, New Mexico had the highest with 78, Washington State followed with 71, and Arizona had the third highest, with 54 cases.

Anna Bean, who is a Puyallup Tribal Council Member and on the Washington task force, said since the task force was created, she has seen more progress than in previous years.

“Some might find it slow work, but we have to make sure that we’re measuring twice and cutting once because this involves actual lives,” Bean said.

Bean said once she became aware of what she called an epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous men, women and children, she could not walk away. “I feel deeply affected by this. These are our relatives. I know somebody who’s been affected, and so for them I carry this work so that they don’t have to carry it alone,” she said.

Bean said to get closer to a solution, it is important to involve as many people in task force operations as possible.

However, one big issue facing all of the task forces is the lack of accurate data, Etnire said. “There’s not a lot of data that’s out there. So do we truly know the whole scope? I don’t believe so,” he said.

Mayes is optimistic. She said the Arizona task force will help bring the many jurisdictions together so that they can begin to coordinate, talk about solutions and take action as a team.

“I think we have to see progress. … We can’t allow this to continue this way,” Mayes said.