WASHINGTON – Arizona border communities face a “humanitarian disaster” in two weeks if the federal government does not step in to help with the crush of migrants expected when Title 42 ends, local officials told a Senate panel Wednesday.

Mayors from Yuma and Sierra Vista along with Pima County’s chief medical officer all testified that their systems are already straining under what have been historically high numbers of immigrants crossing the border. They told a Senate Homeland Security subcommittee that they do not have the staff or equipment to handle any more.

“NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) spend more than $700,000 and use 93,000 pounds of food and clothing,” Yuma Mayor Douglas Nicholls said in his testimony. “Yuma Regional Medical Center treated 1,300 patients at a cost of $810,000, with only one-third of that cost being reimbursed by the federal government.”

The hearing by the Subcommittee on Government Operations and Border Management came just two weeks before the scheduled May 11 end of Title 42, a public health safeguard invoked during the COVID-19 pandemic. Under that regulation, border officials for the past two years have been able to turn back many migrants on public health grounds.

Nicholls cited reports that as many as 660,000 people are waiting across the border for the end of Title 42.

Border communities said they are already overwhelmed: Customs and Border protection reported 191,899 encounters with migrants along the southwest border in March, a jump of more than 35,000 from February.

If the federal government does not step in to help, Arizona’s border towns are bound to face a “humanitarian disaster” in coming months, said Dr. Francisco García, Pima County’s deputy county administrator and chief medical officer.

Sierra Vista Mayor Clea McCaa II said that cartels have disturbed the “quiet, safe lifestyle” of his town by recruiting U.S. teenagers to pick up migrants on this side of the border and smuggle them north. The resulting high-speed chases have led to an increase in car collisions and deaths, McCaa said.

Even with Title 42 in place, McCaa said Sierra Vista’s small police force has to deal with about four to five high-speed “load car” pursuits a day. He said one of those crashes happened 200 yards from his mother’s house, making him fearful for both his loved ones and constituents.

“I want to stop worrying about if my daughter gets back home from volleyball practice. I want to stop worrying about if my mother gets back home from Bible study,” McCaa said to Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, I-Ariz., and chair of the subcommittee.

“That’s what keeps me up at night, that’s what that’s what I worry about,” he said. “When is the next citizen that’s going to be … a fatality because of these load-car drivers?”

Nicholls, who has declared a state of emergency several times in response to the number of migrants, said much of Yuma’s transportation, food, shelter and medical care goes toward caring for them. He said he worries what might happen if the resources are not in place to handle a surge.

“You would end up with releases to the streets of Yuma, up to 1,000 people a day,” Nicholls said. With only a handful of buses leaving town in a day, he worries that some could end up trying to walk to their next destinations “as we enter the 120-degree temperature ranges.”

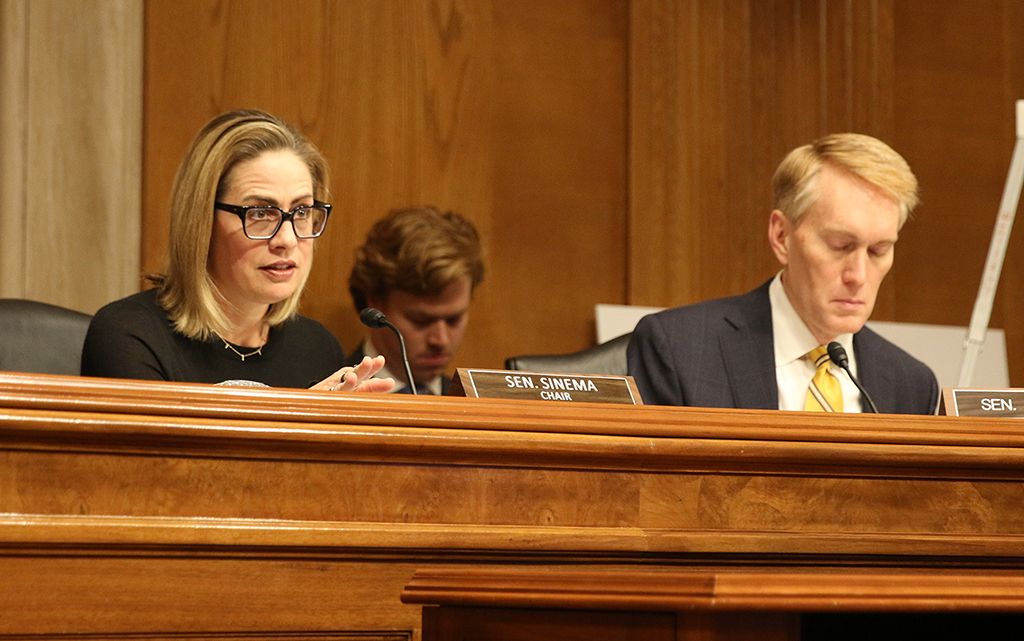

Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, I-Ariz., and Sen. James Lankford, R-Okla., lead the Senate Homeland Security subcomitttee that heard concerns from officials in Arizona border communities about an expected surge in immigrants. (Photo by Alexis Waiss/Cronkite News)

“Yuma is not adjacent to much, so you’re not going to be able to just walk to the next town,” he said. “We’re 180 miles away from the Phoenix metro area, about 150 miles away from the San Diego area.”

García said he faces similar challenges, as Pima County has been “heavily involved in assisting the sheltering, feeding, medical screening” of incoming migrants for the past four years.

“It is the massive and unrelenting flow and volume of asylum seekers that is the most taxing and that is the biggest challenge for us,” García said. “For city and county staff, for humanitarian staff and volunteers, it is unrelenting and exhausting.”

All three Arizona witnesses said that much of the problem comes down to the federal government’s failure to provide consistent funding and communication to local communities. But Garcia said sending money is not the only thing Washington needs to do.

“We need comprehensive federal immigration reform that addresses some of those push factors that are pushing people from their countries,” García said. “That’s not something that we as locals will be ever able to solve. That is something that is in the province of this Congress and the executive.”

Nicholls said U.S. and local officials need to learn from earlier border surges and “pre-position some of those resources” so they are ready to respond. And they need to work together.

“It’s not just a Yuma problem or a city problem. This impacts us as a state and as a country,” Nicholls said after the hearing. “It really shouldn’t be a partisan issue.

“This is about humanitarian concerns, and it’s about border security, and those elements should be in everyone’s benefit, to everyone’s interest,” he said.