A pink sunrise as seen from Hopi Point on the Grand Canyon’s South Rim in this 2018 photo. Tribes and environmental groups are calling for the president to designate an additional 1 million acres around Grand Canyon National Park as a new national monument, to further protect the park. (Photo by M Quinn/National Park Service)

WASHINGTON – Tribal leaders joined state lawmakers Tuesday to call on President Joe Biden to set aside more than 1.1 million acres around the Grand Canyon as a new national monument.

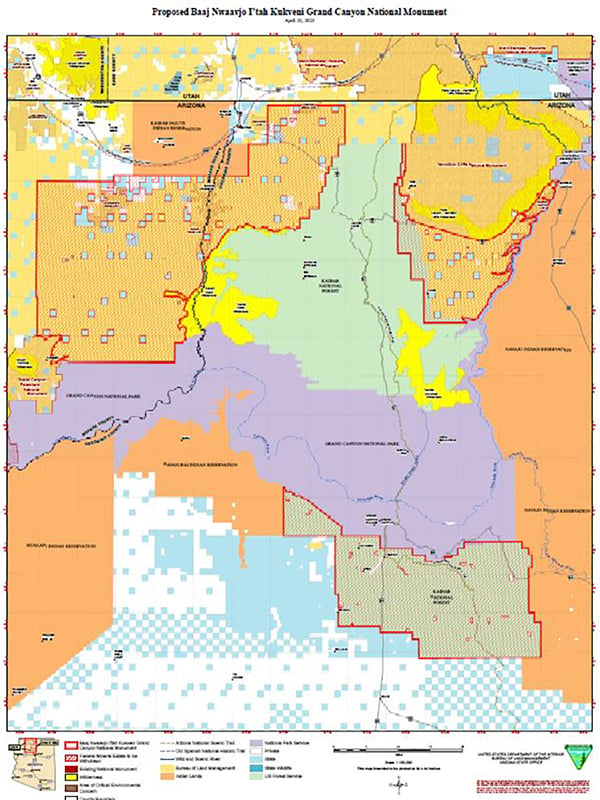

Environmental groups and a dozen tribes in the region say the proposed Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument is needed to protect the area’s water, wildlife, sacred spaces and ancestral homelands from uranium mining and other projects.

“It is our home, it is our land, and our water source, and our very being,” said Havasupai Vice Chair Edmond Tilousi. “Designating these areas as a national monument will protect them from contamination, destruction, or exploitation and the other harmful effects of mining.”

But critics say that banning mining would cripple the region’s economy, and that creating another national monument in a state with large tracts already under federal control is just another example of Washington overreach.

“We want the ability to use the resources that we have in our county to be self-sufficient. We’re not looking for handouts from the government,” said Mohave County Supervisor Buster Johnson, who claimed uranium mining could be worth billions to the region’s economy.

“We’re saying hey, we have these minerals (that) are in the ground that’s here, and we’d like to mine them and become prosperous, you know, like everybody else would,” said Johnson, a longtime critic of the expansion of federal lands in the region.

Areas outlined in red show the footprint of the proposed 1.1 million acre Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni National Monument in northern Arizona, which advocates said is needed to protect water and tribal sites. (Map courtesy Rep. Raul Grijalva)

The call for a new national monument comes just three weeks after Biden used the Antiquities Act of 1906 to set aside more than 500,000 acres in southern Nevada as the new Avi Kwa Ame National Monument. The White House said that site, also known as Spirit Mountain, is historically sacred to a number of tribes in California, southern Nevada and northern Arizona, as well as being home to important geologic features, archeological site and threatened wildlife.

“I think that (Avi Kwa Ame) has started the momentum for … this century, so that we can start building and designating all those religious sites and parts of origins to all Native people,” Colorado River Indian Tribe Chairwoman Amelia Flores said during Tuesday’s press call on the Grand Canyon proposal. “It’s, you know, long overdue.”

Flores and others on the call said Biden should again invoke the Antiquities Act, which allows presidents to set aside lands to protect cultural or natural resources.

“Luckily for the administration, we’ve already done the hard work,” said Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, I-Ariz., during the call. “We proposed a framework that we’ll use to work with the administration and our coalition over the coming months to create the monument under the Antiquities Act.”

Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Tucson, said he and Sinema have had informal discussions with the Biden administration about this designation, and he expects more formal talks to follow Tuesday’s announcement. Grijalva said he is optimistic, given the administration’s focus on tribal sovereignty issues and the recent designation of Avi Kwa Ame.

“Key to the Antiquities Act, and key to a designation, is the Indigenous association and relevance and importance. The Grand Canyon obviously fits that to a T,” Grijalva said. He cited the tribal interest in Avi Kwa Ame and Bears Ears National Monument in southern Utah, both of which were created using the Antiquities Act.

A request for comment from the Interior Department on the Grand Canyon plan was referred to the White House, which did not respond Tuesday.

It’s not the first time the federal government has put land around the Grand Canyon off-limits to mining – or the first time Grijalva has tried to expand those protections.

The footprint of the proposed Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument is a smaller version of the 1.7 million acre Grand Canyon Heritage National Monument that Grijalva first proposed in 2015. That proposal would have included the Kaibab National Forest north of the canyon.

The Canyon Mine, near the Grand Canyon, has yet to produce uranium, but it is not subject to a 2012 mining ban because it was initially approved in 1986. (File photo by Jake Eldridge/Cronkite News)

The current plan skirts that part of the forest north of the park, but still includes sections of the Kaibab National Forest south of the Grand Canyon. The current plan would take up large chunks of Mohave and Coconino counties, and border parts of the Navajo, Kaibab Paiute and Havasupai reservations.

In 2012, the Interior Department imposed a 20-year moratorium on new permits for mines on more than 1 million acres around the Grand Canyon. Coconino County Supervisor Lena Fowler said the new monument designation would make that ban permanent but would not disrupt grazing, logging, hunting or other outside recreation.

“There are currently approximately about 6,000 active (mining) claims that need to be banned, this will permanently ban those claims,” Fowler said. “The monument is so important to our region, and tribes that hold this area as a sacred place, and also to residents that live in the area.”

Supporters point to an August poll by the Grand Canyon Trust that said two out of three Arizona voters support a permanent ban on uranium mining around the Grand Canyon.

But Johnson said the moratorium has changed Mohave County mining communities for the worse.

“In the mining industry, they pay well. We’ve had some communities that, when they put the moratorium in, the men had to leave,” Johnson said. “The families deteriorated because the men weren’t around … schools closed. Jobs just aren’t there and communities went under.”

He said federal officials are not concerned about Mohave County’s priorities, only what looks good politically.

“It sounds good. ‘Oh, we’re saving the environment,'” Johnson said. “No, you’re not saving the environment. You’re leaving a natural resource for the security of our country, you’re just taking it away from us.”

But for Carletta Tilousi, a Havasupai tribal leader, who said she has been fighting to protect Indigenous lands from uranium mining since she was 16 years old, it’s time to stop mining around the canyon.

“We understand and see the history of what uranium has done in the Southwest to our neighbors, the Navajos and Hopis,” Tilousi said. “And we don’t want to see that happen to our small tribe.”