WASHINGTON – Arizona is doing all it can to improve air quality but will not meet federal standards as long as pollution from other jurisdictions can drift across its borders, the director of the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality testified Wednesday.

Karen Peters said the Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed “Good Neighbor Plan,” to limit emissions in states whose pollution affects downwind states, is “crucial” to addressing pollution in downwind states like Arizona. She pointed to areas like Yuma, which generates very little smog on its own but it still out of clean-air compliance.

“Yuma is heavily impacted by ozone transport from California and Mexico,” Peters said in testimony to the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee. “There is virtually nothing that can be done in terms of local emission reductions to reduce ozone pollution in the Yuma nonattainment area.”

The same is true in the Phoenix-Mesa area, where Peters said there are “very few, if any, remaining emission reductions available” to help the region attain clean-air standards.

But critics at the hearing called the plan an expensive and heavy-handed attempt to force federal policy on states and said it would force businesses and power plants to shut down, what one witness called “sort of shooting ourselves in the foot.”

“It threatens U.S. manufacturing, including the U.S. forest products industry,” said Paul Noe, vice president of public policy for the American Forest and Paper Association. “Ultimately, this is a threat to the American worker – men and women with high-paying, high-skilled manufacturing jobs, both rural and urban, in red and blue states.”

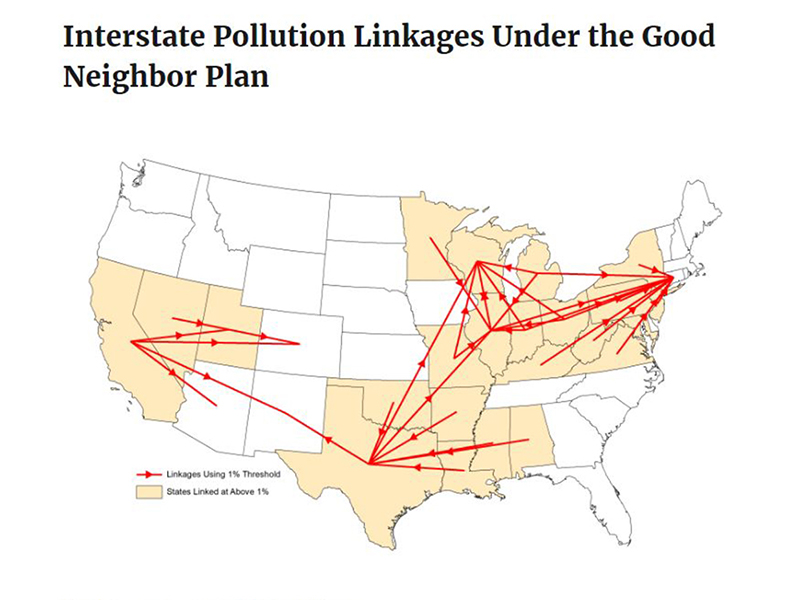

Shaded states would be subject to the EPA’s Good Neighbor Plan, and the arrows show the transmission of pollution between those and other states. (Map courtesy Environmental Protection Agency)

The Good Neighbor Plan calls for significant reductions on ozone-forming emissions from power plants and industrial facilities in 23 states whose bad air is carried to other states. In addition to power plants fired by fossil fuels, it would also apply to facilities manufacturing iron, steel, cement, paper, glass, and petroleum and coal products, to natural gas transmission and metal ore mining.

Most of the states affected by the plan would be subject to both power plant and industrial restrictions, but California would only be subject to industrial emission limits while Alabama, Minnesota and Wisconsin would only have to rein in power plants.

Arizona is not currently one of the states that would be subject to the rule, but an EPA spokesperson said Wednesday that “further analysis is warranted” on whether it will apply to the state.

Dr. David Hill, an American Lung Association board member, pushed back against critics who cited the economic costs of the new regulation, claiming that it could actually spur more economic activity through reduced health burdens.

“The EPA has projected that it will prevent premature deaths, that it will avoid hospitalizations, that it will cut asthma exacerbations,” Hill testified.

“School absences will be decreased by over 400,000, and when kids miss school, parents miss work. Over 25,000 lost work days will be avoided,” he said. “So there will be significant health care and economic benefits to instituting the rule.”

Sen. Ben Cardin, D-Md., acknowledged concerns about costs of the plan, but said they were outweighed by the health benefits. The challenge for lawmakers, he said, is to “find that sweet spot because the risk factors to our population and cost factors to our population indicate that the federal government today is not carrying out its responsibility.”

But Sen. Cynthia Lummis, R-Wyo., said she worries that the rule would force power plants to close, removing more than 14,000 megawatts of electricity generation from the system, which would “cripple” affordable power for the nation.

“The premature forced closure of coal-fired power plants in this nation is a danger to American energy security and grid reliability,” Lummis said. “For this reason alone – not to mention the 90,000 direct coal mining jobs in 26 states, including Arizona, Oregon and Pennsylvania, just to name a few – this administration must reverse course.”

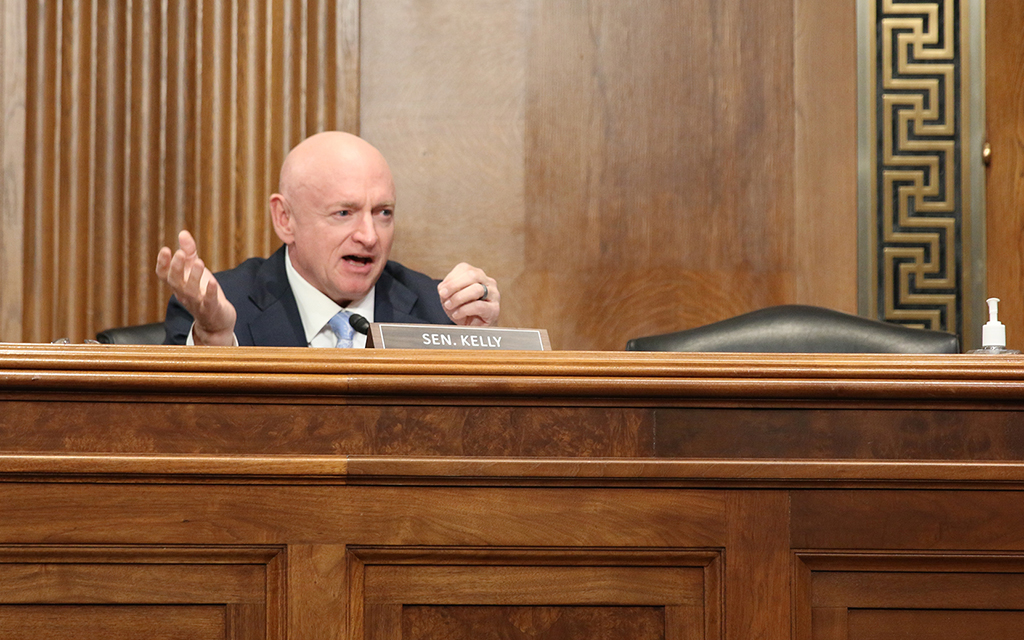

Sen. Mark Kelly, D-Ariz., countered with an economic argument for the plan, pointing to Yuma, which is bordered on the west by California and the south by Mexico. The city of fewer than 100,000 people could face stringent economic limitations if its neighbors are not held accountable for the pollution they are causing in the area, he said.

“Because the area exceeds the EPA’s standards for ozone, there are limits imposed on the region’s economic growth,” Kelly said. Of the pollution in Yuma, “10% comes from somewhere within Arizona, but basically nothing comes from Yuma County.”

Peters said about 40% of the ozone in the Phoenix area was generated within the state but that the rest comes from other sources, either natural background sources or other states or even countries.

Kelly was not able to answer Lummis’ question about how much pollution might be coming from Chinese manufacturing. But he said he would not be surprised if it was true, calling on his experience as an astronaut when he said he was able to see sand and smog drifting across national borders.

Peters said there are things that can be done to help reduce local pollution, but many of those things are not within the state’s jurisdiction, a situation she finds “frustrating.” Despite Maricopa County failing to meet ozone standards, Peters said the state made some progress in improving air quality.

“Ozone emissions have gone down over the last 20 years in the Maricopa area,” Peters said after the hearing. “But you know, time is not on our side. We need to do more sooner.”