Recent data show a snowy start to 2023 for the Colorado River basin, with heavy winter precipitation in the Rocky Mountains projected to boost spring spring runoff into Lake Powell to 117% of an average year’s flows.

But scientists say that while this winter’s snow may provide a temporary boost to major reservoirs, it will not provide enough water to fix the Southwest’s long-term supply-demand imbalance, as the beleaguered river continues to grapple with climate change and steady demand.

Snow in Colorado is an important factor in determining the amount of water that will flow into the Colorado River system each year. About two-thirds of annual flow starts as snow high in the mountains of Colorado. Across the state, snow totals are almost all above average, with most zones at 120 to 140% of normal for this time of year.

Northwest Wyoming and central Utah, which also contribute to the basin’s water supply, posted January snowfall totals that nearly broke precipitation records. Many parts of Utah are showing snow totals above 170% of average, boosting the odds of above-average runoff in the spring, and fostering memorable seasons for the area’s ski resorts.

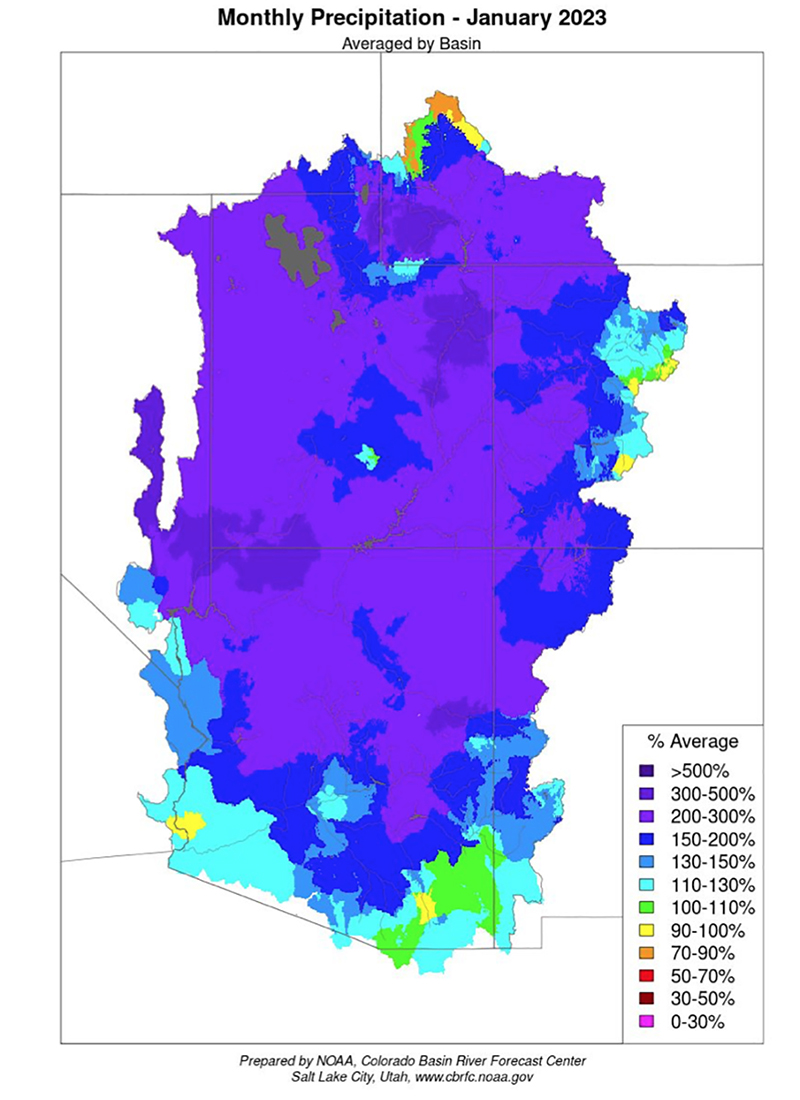

Recent data from the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center show heavy precipitation this winter through much of the Colorado River Basin states – especially Utah, Wyoming and Arizona. (Graphic by Alex Hager/KUNC)

The new data come from the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center, a branch of the National Weather Service that tracks water along a river which supplies 40 million people around the Southwest.

In the Colorado River’s Upper Basin – which includes parts of Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico – the strongest precipitation fell in southwestern Colorado, according to data last month. The Gunnison, Dolores and San Juan rivers all saw January precipitation that ranged from 160% to two times the average. Meanwhile, the lowest January precipitation totals were along the Eagle River in central Colorado, and the Green River above Fontenelle Reservoir in Wyoming.

The Lower Colorado River Basin – which includes parts of Nevada, Arizona, and California – also saw strong precipitation. The Virgin, Little Colorado and Verde rivers all saw January precipitation above 200% of normal. Rain and snow in the Lower Basin is typically less important for the Colorado River’s flow, but is helpful for plants, farms and ranches, and wildfire mitigation.

Precipitation totals are “exceeding expectations because La Niña conditions usually result in drier than average winter weather across the southwest U.S.,” said Cody Moser, a hydrologist with the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center.

La Niña is a weather phenomenon during which cold water in the Pacific Ocean alters temperature and precipitation patterns over the Western U.S. Its effects are not guaranteed, but typically mean a colder, wetter winter for the northwestern portion of the country, and a warmer, drier winter in the Southwest. The dividing line often falls in the middle of Colorado.

When it comes to predicting the amount of water in the Colorado River each year, snow totals don’t tell the full story. Scientists look to soil moisture for a clearer picture of how much water will actually reach the places where humans divert and collect it.

This year, soil moisture in the mountains is well below average. That could prevent some melting snow from ever reaching the Colorado River. That soil acts like a sponge, soaking up water before it has a chance to flow downhill to streams and lakes. Scientists have recorded years with 90% of average snowpack, only to see 50% of average runoff into reservoirs.

Even the concept of “average” has changed due to warming temperatures. In spring 2021, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shifted how it calculates averages for all of its data.

Every 10 years, NOAA moves the three-decade window that it uses for averages. But the rapidly accelerating effects of climate change mean the current window from 1991 to 2020 sticks out from previous 30-year periods because it includes the hottest-ever period in recorded history.

Runoff season typically peaks around late May or early June. Those flows go on to replenish Lake Mead and Lake Powell – the largest and second-largest reservoirs in the U.S., respectively – which have both dipped to historic lows in recent years. Two decades of lower snow and drier soil have chipped away at water supplies, and the seven states that use the Colorado River have struggled to agree on a plan to reduce their demand.

Climate scientists stress the need to adapt demand in a way that works with current conditions and steels the region against a future that will likely bring even drier conditions. Brad Udall, a water and climate researcher at Colorado State University, said the region would need five or six years with 150% snowpack to refill Lake Powell and Lake Mead

“We need to continue to plan for the worst here,” Udall told KUNC in January. “That’s what we’ve seen the last 23 years. That’s what these warming temperatures continue to tell us.”

– This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC in Colorado and supported by the Walton Family Foundation. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial coverage.