Arizona native and former Interior Secretary Steward Udall speaks at Canyonlands National Park in this undated photo. A new documentary about the late Udall aims to restore his legacy. (Photo by Neal Herbert/Canyonlands National Park)

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland speaks at the screening of a documentary on a former secretary, Arizona native Stewart Udall, who supporters credit with pushing a range of environmental gains during his tenure. (Photo by Alexis Waiss/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – John de Graaf says there was a time when a list of Arizona political icons would have included Barry Goldwater, John McCain and at least one other – Stewart Udall.

But de Graaf worries that Udall, an Interior secretary widely recognized as the modern father of conservation, is being forgotten, a slight that he hopes to reverse with a recently released documentary.

“He’s just a remarkable, not only state figure but national and international figure,” de Graaf said. “He was an ambassador for the United States for conservation and parks all over the world. And the fact that most young Arizonans have never even heard of him says something about our lack of interest in understanding of history in the United States.”

That story is told in “Stewart Udall and the Politics of Beauty,” an hourlong documentary that premiered Jan. 31 in an Interior Department building named in Udall’s honor. It paints Udall, who died in 2010, as a uniting force revered for pushing forward the environmentalist movement in addition to promoting desegregation and tribal sovereignty.

For de Graaf, a Seattle native who fell in with Arizona’s history and Udall’s legacy, the story is more important now than ever.

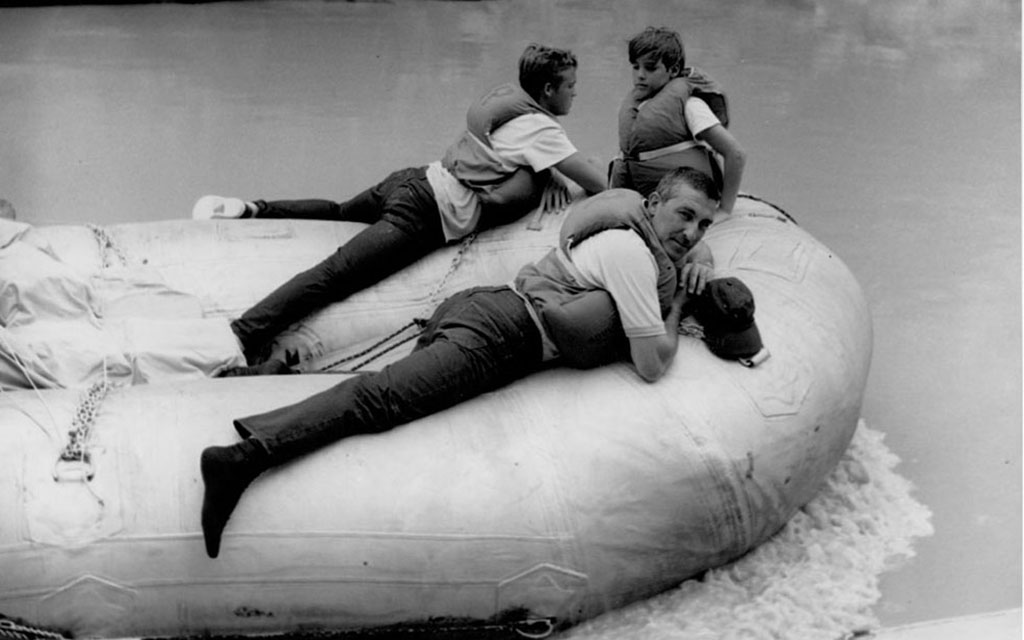

Then-Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall rafts the Colorado River near Elves Chasm with Dennis Udall, sitting, and Jack Metzger in this June 1967 photo. (Photo by Dave Beal/Grand Canyon National Park)

“While it (Udall’s public career) takes place in the … 1950s and ’70s, it is absolutely current to the issues that we face today, and to provide us inspiration that we can actually make the changes we need to make,” de Graaf said. “And that’s the big theme of this film.

“With the story of one person, we can tell a huge story of the American history of that period,” he said.

The film, which premiered on what would have been Udall’s 103rd birthday, highlights his accomplishments and challenges while serving as Interior secretary in both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. He pushed to recruit employees of color to the National Park Service, oversaw the creation of more than 80 national preserves and refuges, is credited with inspiring first lady Ladybird Johnson’s national beautification campaign and sought greater self-determination for tribal nations.

It features the perspectives of those in his inner circle – family, co-workers and close friends – in addition to environmentalists, historians and people from marginalized communities who were affected by his work.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, in remarks before the premiere, credited Udall with shaping “the department into much of what it is today.” She said her own love of the outdoors was inspired by regular trips to the outdoors with her family, childhood trips that were similar to those of the Udall family that were highlighted in the documentary.

“I learned through those experiences how these lands sustain our health, communities and our sense of wonder,” Haaland said. “I didn’t realize it then. But conservationists like Stewart Udall helped make those formative experiences possible for my siblings and me, and of course, for countless others.”

Udall was born in St. John’s in 1920 into a family with a dynasty-like reputation, serving in local and federal offices for over a century.

A Democrat, Udall was elected to Congress in 1954 from eastern Arizona and would be re-elected three times before resigning in 1961 to become Interior secretary. He was succeeded by his brother, Mo, who held the seat for 16 terms and mounted an unsuccessful bid for the Democratic nomination for president in 1976.

Stewart’s son, Tom Udall, served two terms as New Mexico attorney general before being elected to Congress, where he spent 22 years as a House member and, later, a senator. He was named U.S. ambassador to New Zealand in 2021. From 1998 to 2008, Tom Udall served in Congress with his cousins, then-Rep. Mark Udall, D-Colo., and Sen. Gordon Smith, R-Ore., one of few times in history where several members of the same family held congressional office.

Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Tucson, said he met Stewart Udall when the former secretary endorsed Grijalva’s congressional bid. As an Arizona Democrat who has championed environmentalism in the House since 2003, Grijalva said he considers Udall an inspiration to his politics.

“I grew up with that Udall ethic when it came to environmental issues and protection and conservation and then species protection,” Grijalva said. “I think representing that part of the country, I feel a responsibility to those issues, very much so.”

Udall’s daughter Lori, who was on hand for the screening, said the film captured his essence, even if it was a what she jokingly called “kind of a puff piece.” She described her father as a “deep feeling person” who was devoted to leaving the country in a better place, unlike some politicians today who “go into politics for egotistical reasons.”

“He wasn’t doing it for himself. He wasn’t doing it for fame. He wasn’t doing it for money. He was doing it to make the country better,” Udall said. “That’s an important lesson: When you’re elected, you’re elected by a group of people and you need to serve them.”

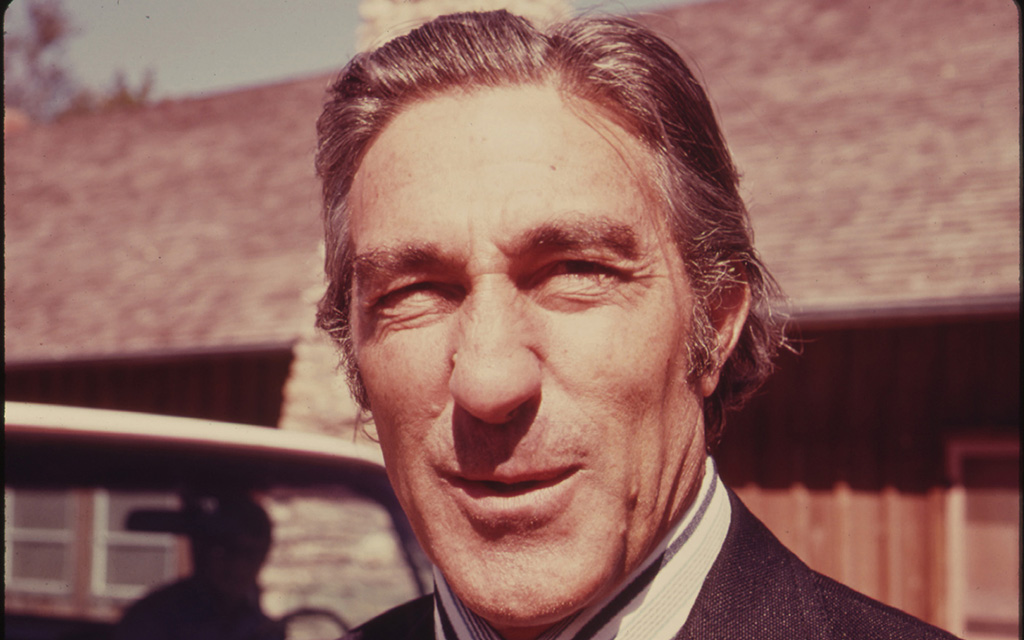

Stewart Udall at an event at Tallgrass National Park in Kansas in 1974, five years after his term as Interior secretary ended. (Photo courtesy the National Archives)

De Graaf said there was another lesson Udall can provide us today: Finding common ground is possible.

“In many cases, sometimes his strongest supporters were Republicans, and a few of his strongest opponents were Democrats, including Jim Crow Democrats from the South,” de Graaf said. “He proved that we could come together as people and we could make these decisions that benefited generations to come.”

His tenure saw the passage of the Endangered Species Act, the Land and Water Conservation Fund, and clean air and water legislation, among others. He is credited with giving tribes a voice at the table for the first time, what Cherokee Indigenous rights activist Rebecca Adamson described in the film as “Stewart standing by our side, we could see Stewart in our circles, we could see Stewart in our ceremonies.”

When Udall became secretary, there were no federal park rangers of color. Robert Stanton, one of the first African Americans hired by Udall to work as seasonal national park ranger, ultimately rose to become director of the National Park Service.

“He was a student of history, and he knew that the federal government was not open to all citizens in terms of seeking employment,” Stanton said during a panel at the screening. “But he had the courage … to make that happen.”

Grijalva said it’s important to memorialize those contributions from an Arizona icon who “reminds us about the conservation ethic, the protection ethic of our public lands and waters … the importance of the voice of Indigenous people and tribes in this country.”

“It’s a story of a man that that shouldn’t be forgotten in terms of the contributions he made, not just to where I’m from, and he’s from, but nationally,” he said.