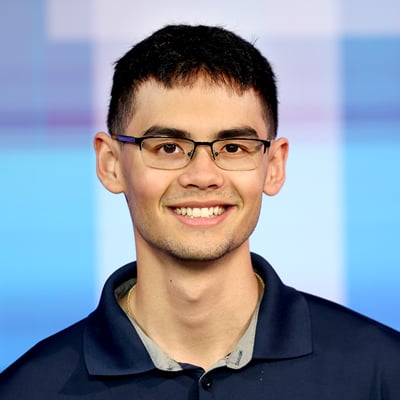

Darren Woodson (fifth row, second from left) starred on the Maryvale Panthers varsity football team before walking on at Arizona State University. (Photo by Robert Crompton/Cronkite News)

PHOENIX — Outside of the Maryvale High School cafeteria, two men named Don Bocchi and Darren Woodson met to discuss Arizona State football. The year was 1987. Bocchi, still in the early stages of what became a decades-long stay with the program, was ASU’s recruiting coordinator. He wanted Woodson — and for good reason.

All it took was a single summer camp – coordinated by Bocchi – for the west Phoenix native to stand out. Even without pads and the platform to pop them, Woodson’s Division I talent was apparent through the way he “approached the game and approached his craft,” in Bocchi’s words. Later attending a game during Woodson’s senior season, Bocchi had all but decided.

Darren Woodson needed to be in Tempe.

Aside from his athletic upside, Woodson, the person, was whom Bocchi sought. Raised in a Maryvale neighborhood marked by juvenile delinquency and gangs in the 1980s — per an ASU study — under a single-parent household as the youngest of four, nothing negative could be said about his character. Woodson’s mother, Freddie Luke, said the establishment of what’s right, what’s wrong and what’s to happen when a wrong is done was an early emphasis in his life.

A scholarship offer was seemingly inevitable subsequent to one final conversation. The topic: Woodson’s academic transcript. What started as a formality ended as a swift reality check.

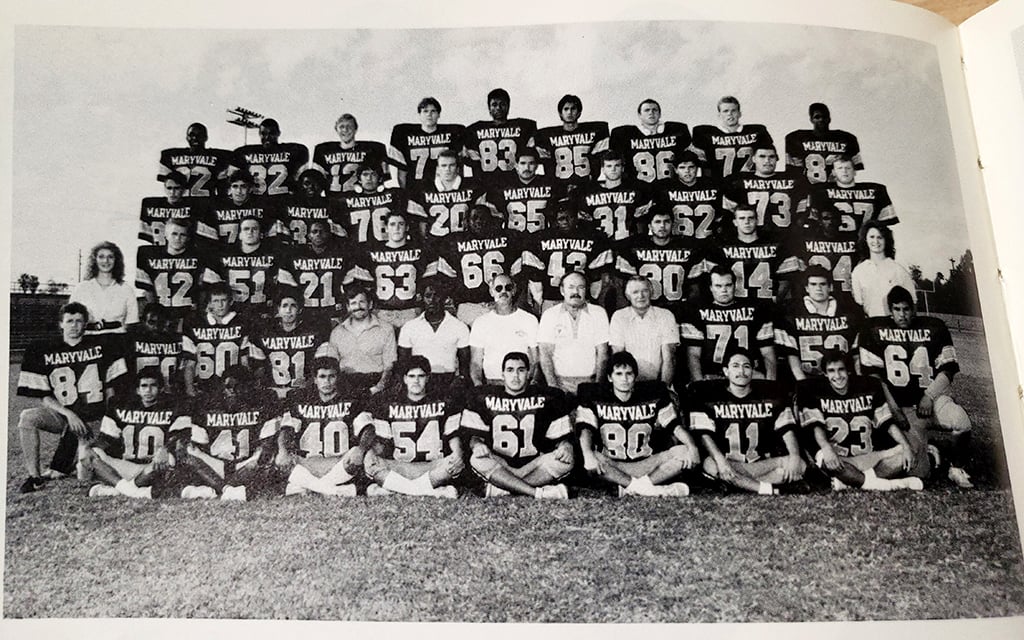

Darren Woodson’s Maryvale yearbook photo in 1985. (Photo by Robert Crompton/Cronkite News)

“I looked at the transcript and I’m looking at it — and this is my first look at it,” Bocchi told Cronkite News. “I’d look at the transcript, then I’d look up at him. Then I’d look at the transcript, then I’d look up at him. He says, ‘Coach,’ he says, ‘Is there something wrong?’ I said, ‘Darren, there’s nothing right.’”

Woodson had two options. He could either spend two years at a local community college or attend ASU under its modified interpretation of Proposition 48. Unlike its enforcement in the NCAA rulebook, which stated that three scholarships could be used for a Prop. 48 player to be housed on campus, ASU President J. Russell Nelson didn’t allow scholarships to be offered to academically-ineligible recruits. If Woodson wanted to eventually play for the Sun Devils, he’d need to pay his way through a freshman year with 24 passing credits that would only then enable him to officially join the team on scholarship for the following summer — as was promised by John Cooper, ASU’s coach at the time.

Neither Woodson nor Luke had the means for that amount of money, and a loan appeared to be the only possible payment method.

Before he could become the three-time All-Pro player who won three Super Bowls as part of a Dallas Cowboys franchise for which he holds the all-time tackles record (1,350), the decision to be or not to be an ASU walk-on ahead of a year of academic toil was a life-changing dilemma. But Luke didn’t hesitate. She understood it was as worth it then as it is now, just hours away from potentially having her son picked for the Pro Football Hall of Fame Class of 2023.

“There was no risk at all when I said, ‘OK, let’s go borrow some money,’” Luke said. “So that’s what I did, and it just took off from there. I think any parent that has the kid that knows what he wants to do, it’s actually what a helping parent would do no matter what to give him whatever gain in life that we possibly can.”

Eight months. That was Woodson’s window to make good on his mother’s continued investment. Because he wasn’t provided with on-campus housing, Woodson completed most of his school work at home with no tutors and not nearly the same level of access to educational resources as other athletes.

He was on his own.

His mom worked multiple jobs to keep her finances afloat. Bocchi was concerned with practices and games during the fall semester as well as recruiting trips in the spring. And Woodson’s closest childhood friends, who included ASU alumni Phillippi Sparks and Kevin Miniefield, were occupied attending to their own futures: Sparks in junior college, though he was also given Woodson’s Prop. 48 option, and Miniefield entering his senior year at Camelback High School. Woodson didn’t even have teammates.

Though Woodson was still rostered as a walk-on, he wasn’t allowed to practice, play or do much of anything with the Sun Devils before, during and after their 1987-88 season.

“Not being affiliated with the team, not having the camaraderie (of) having guys give you an example of what’s going on,” Sparks said, “I bet you that right there I think was probably the hardest transition.”

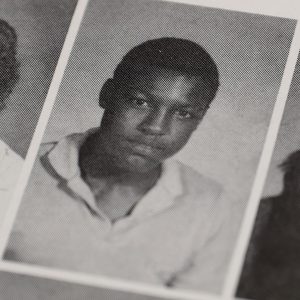

Darren Woodson was named Maryvale’s homecoming prom king in 1987. (Photo by Robert Crompton/Cronkite News)

Nothing about Woodson’s situation was particularly standard, including his classes. He worked within the parameters of S.T.A.R.S., an ASU program meant to aid the academic efforts of those students “who had all the ability and should have been doing better,” according to Bocchi. Because of it, Woodson found himself especially challenged to enroll in the 24 credits of ASU coursework that he needed.

In S.T.A.R.S., Woodson’s 077 remedial algebra class was outsourced to South Mountain Community College — which meant the associated credits weren’t transferable. Bocchi wasn’t aware of Woodson’s status as a part-time enrollee until the 1987 fall semester had begun, but he presumably cared enough to put his pride aside and hustle to insert Woodson into an ASU section of the course in question.

“I called every math teacher at Arizona State that taught 077 math and asked them, I said, ‘Put Darren into your class late. He will not miss a class. And he’ll take your class again in January. You give him an incomplete at the end of the term,’” Bocchi said. “I found one lady that would do it.”

Any grade Woodson received was his responsibility, but Bocchi’s support appeared to be similar in magnitude and intention to that of Woodson’s own mother. Maybe Woodson didn’t need it in bulk, at least at the time. Perhaps the unconditional backing of Bocchi and Luke was more than sufficient.

The results indicated as much: Woodson finished all but one class with a C or better, per Bocchi.

“He did a phenomenal job in guiding me in the right direction,” Woodson said of Bocchi.

“I had to just be a student, stay in contact with Bocchi on a weekly basis and Bocchi basically guided me through the process. He believed in me.”

That confidence and support was so fierce, Woodson’s guaranteed four-year scholarship survived the uncertainty of a coaching change.

After a three-year tenure that included the program’s first Pac-10 Championship and Rose Bowl win — which remains the case today — Cooper moved to Ohio State, where he continued what ended as a considerably successful coaching career. Larry Marmie, who hadn’t yet started his decades-long career as an NFL assistant coach, was hired in Cooper’s place ahead of the 1988-89 season.

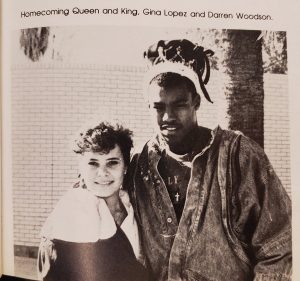

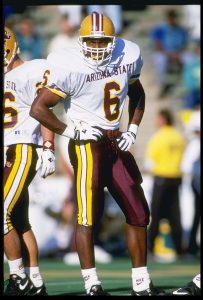

Arizona State University Hall of Famer Darren Woodson is in the running for enshrinement in the NFL’s Hall of Fame after a long and fruitful professional career. (Photo by Otto Greule Jr./Allsport)

Fortunately for Woodson, Bocchi was still on staff.

“I said to the head coach, and we were very close, I said, ‘Darren and Freddie are coming over at lunchtime to sign his scholarship papers,’” Bocchi said. “The coach says to me, ‘We only have one scholarship left.’ I said, ‘I know. We’ve been saving it for Darren.’ He said, ‘But we only have one left.’ I said, ‘That’s all we need.’”

At last, it was time to play football. After managing personal workouts with family and friends for a year, Woodson’s first Sun Devils practice was specifically held for freshmen several days before the official start of preseason camp.

In learning more about its newcomers, the ASU coaching staff was focused on figuring out players’ positions. But Woodson’s standout athleticism didn’t make it easy on them.

“By the time we got Darren to this camp, everybody wanted him,” Bocchi said. “The linebacker coach wanted him, the secondary coach wanted him, the running back coach wanted him. I was coaching wide receivers, and just for fun, I said, ‘Hell, I’ll take him.’ We could’ve used seven of him, at least.”

As much as it may have come as a surprise to his coaches, Woodson wasn’t known by most of his teammates. Kelvin Fisher, who later served as a co-captain with him during their senior season, was among the few who were familiar with Woodson — mostly because Fisher was also recruited by Bocchi, who told him all about the Sun Devils’ eventual three-year starting outside linebacker.

“It was weird because I don’t think a lot of the guys on the team knew that he was on our team, and he was just going to school,” Fisher said. “So a lot of guys was like, ‘Man, where did he come from? Who is that?’”

Indeed, who is Darren Woodson?

To fans, he is the embodiment of every aforementioned accolade. And if he notches another to his name at Thursday’s NFL Honors, where the incoming Pro Football Hall of Fame class will be revealed, it will reinforce his greatness in the sport as he and Luke and Bocchi and a flurry of others believe should’ve already happened: Woodson has fallen short as a semifinalist on six prior occasions.

But that won’t define Woodson.

The son of a hard-working single mother from the west Valley whose childhood dream was to be drafted in the NFL has achieved most everything he ever wanted. But Woodson’s proudest moment, according to Bocchi, came when Woodson handed his mother a diploma from ASU.

“Never was he looking to shine a personal light on him,” Bocchi said.