PHOENIX – On Opening Day in 1947, droves of fans trekked to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn to see a 28-year-old take the plate in a historic moment for Major League Baseball.

More than half of the 26,000 fans in attendance were Black, but everyone came together to pack the stands to witness the first at-bat by a Black baseball player in a MLB game.

Baseball has come a long way since Jackie Robinson etched his name in the game’s history books 75 years ago, but the feeling of being the odd one out still remains for many players of color. Only 7% of major league players are Black, but the next generation of minority players hope to increase that number.

The league is looking to help in those efforts. In mid-January, MLB held the MLB DREAM Series in Tempe, a three-day amateur development experience designed for minority pitchers, catchers and positional players to gain exposure in a predominantly white sport.

Over 80 high school players from across the country participated in the event during the holiday weekend devoted to remembering Martin Luther King Jr.

“I think it was cool to be able to be around that with all of the scouts and everything there. All the kids, all the Black kids that may not get the same looks as other kids in baseball,” said Dean Moss, a sophomore outfielder at Florida’s IMG Academy who has committed to Vanderbilt.

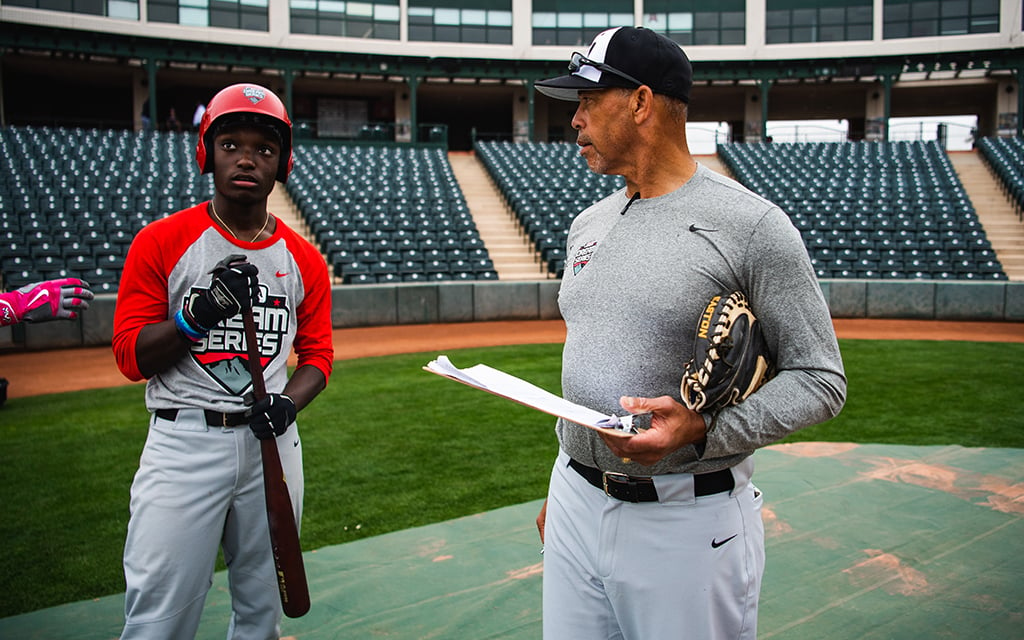

LaTroy Hawkins, left, coaching LJ Mercurius believes the Dream Series allowed him to give back to the game that gave him so much. (Photo by Kelsey Grant/MLB Photos via Getty Images)

Numbers trending backward

Although the DREAM Series aims to provide Black players a chance to learn from former players and showcase their talents, when it’s over many participants return home to play on teams with mostly white teammates.

Nuri Todd, a Brophy College Preparatory senior who participated in a similar event at the Hank Aaron Invitational in 2019, doesn’t take for granted the opportunity to play with two minority teammates under a minority coaching staff. Todd, a shortstop, led his team with 13 steals last season and maintained a .405 batting average.

Playing alongside players who look like him and seeing successful initiatives like the Dream Series renews Todd’s hope that change is on the way.

“(The DREAM Series) means a lot, it means that we’re getting help from those that played previously, right, and they want to see our culture back in the sport,” said Todd, a Long Beach State commit. “So I appreciate the support from them, and I also appreciate support from MLB, in general, for making an attempt.”

From the 1947 season to 1981, the number of Black MLB players steadily grew each year, from 0.9% to 18.7%, according to the Society for American Baseball Research. By 1980, 71.1% of MLB players were white, while 17.4% were Black.

In 2002, it dipped to 10.2%.

With Black participants slipping to 7% in 2022, the past two decades have erased any signs of true progress.

“My grandfather played baseball, and it feels like it skipped a generation, right? So during their time, that was what was popular,” Todd said. “So you know, you get into the ‘80s and all the way up to the 2000s – that’s when we drop off, right? We’re focusing on football before focusing on baseball. That’s what gets the attention. That’s what gets the girls. You know, you want to play that sport. You want to be that guy, right?”

LaTroy Hawkins, a former major league pitcher who played 21 years on 11 different teams and coached at the DREAM Series, believes the next generation of Black baseball players have the free will to promote themselves and vocally influence the game to a higher degree than his peers were afforded.

Hawkins couldn’t remember a moment during his career when he had more than four Black teammates at one time.

“We didn’t have that opportunity, the opportunity wasn’t there (to advocate for ourselves),” said Hawkins, who was drafted in 1991 by the Minnesota Twins. “The game was completely different. The culture of the game was different. The culture of the game was you come, you do your work, you work hard, you go home, and that’s that.

“This generation came in, telling us that our unwritten rules were stupid, you know? And the game should be fun, it should be vibrant, and everybody should want to play it because this is what we do. We didn’t get to be ourselves. I did because I wasn’t a guy that was very emotional. But the guys who were, they were all mislabeled. The game needs us. The game needs African Americans in it.

“The game needs everybody in it. But we have to find a way to continue to get African Americans to play a game, play this game of, you know, baseball. It’s not an easy sport, and it’s become a very expensive sport.”

Brophy Prep’s Nuri Todd believes basketball and football are more popular sports than baseball among younger Black athletes. “That’s what gets the attention. That’s what gets the girls,” he said. (Photo by Grace Edwards/Cronkite News)

The cost to play

The average cost of playing on a travel baseball team is $3,700, reports USA Today, but the tab for travel, food, equipment, fees and training can cost families upwards of $8,000.

The rising cost of equipment and travel, especially since the start of the pandemic, creates a unique challenge for minorities to be seen.

The financial gap in the United States only compounds the rising costs for minorities. As of 2021, the median net worth of Black households was about $24,000, or about one-eighth of $188,000 for white households, according to a study by the McKinsey Global Institute.

In 1968, at the peak of the Civil Rights movement, Blacks averaged an annual income of $6,674 compared to the $70,786 median average for white households.

The gap only widened with time, and in 1989, Black households brought in only 5% of the median household including whites ($129,771).

For many participants in the DREAM Series, the event was a chance to gain exposure from major league scouts without feeling a financial burden. USA Baseball covers all expenses for the players, but some players feel they shouldn’t need to participate in an event specifically for minority players just to be seen.

“It’s really cool to see at the DREAM Series, when there’s a kid who may not have the resources and he’s there and he absolutely goes off and all the scouts love him, when they haven’t seen him before,” Moss said. “But it’s also sad because you don’t know why they haven’t seen him before.”

While the culture surrounding baseball is changing, and more Latin American players begin to rise up the ranks, it remains unknown if the numbers will continue to tread downwards or increase with the next generation.

“I think that the worst thing we’ve ever done as a society is made baseball too expensive for one group not to be able to afford,” Hawkins said. “I think the killer for African Americans has been travel baseball. That’s been the killer because every kid that’s just an OK player that comes from a family that economically can have some extra money. Their dad can become their coach and they create their own team. And I think that’s what single-handedly killed Black minority kids from playing the game.”

Former major leaguer Lou Collier believes that while the MLB is doing a great job with its programs, an opportunity remains to reach more youth in lower income areas. (Photo by Kelsey Grant/MLB Photos via Getty Images)

Change since the 1980s

DREAM Series coach Darrell Miller, a former California Angels catcher and first baseman, feels teams were more open to Black players behind the plate back in his playing days.

“So for me, at least, I think it was, I wouldn’t say difficult. It was hard,” Miller said. “And I think the one thing I felt as an African American catcher is that I think, there were probably more people open to having an African American catcher than there are today.”

After he was drafted as a catcher by the Angels in 1979, Miller was immediately moved to first base before transitioning to the outfield later in his career. Miller believes that while the game has changed immensely since his playing days, Black catchers are overlooked for more experienced catchers from Latin American countries.

“I think there’s a lot of catchers that can play, but similar to what happened to me, if you could run, you know, you are then put in the outfield, and I ran a 6.60. So I was a pretty good runner,” Miller said. “It just was hard to be able to convince someone that even though you can run the speed, you can hit, you have power that, you know, that’s still a safe place for you to stay.”

For Todd, playing shortstop is deemed unconventional for Black players, but he hopes Generation Z players like himself understand playing in the outfield isn’t required to play the game.

“There’s kind of an idea of African Americans playing a certain position on the field. And I think we’re getting to the barrier, and we’re about to completely break it open,” Todd said. “Infielders previously were marketed as outfielders, right? You can only run, you can only run fast. That’s all you’re good with, right? So I think as we can move forward and continue to see different faces in different positions, we’re more open to it.”

IMG academy sophomore and Vanderbilt commit Dean Moss feels disappointed by the lack of American born Black players in the 2022 World Series between the Houston Astros and Philadelphia Phillies (Photo by Kelsey Grant/MLB Photos via Getty Images)

MLB’s lack of diversity exposed

No Black American born players were featured in last year’s World Series between the Philadelphia Phillies and Houston Astros.

While players of color made the Fall Classic rosters, critics interpreted the series as a step back for a game that had come so far since Robinson broke the color barrier.

“You know, it’s not a good thing, and I think in baseball sometimes there can be moments where there’s a white player and he might get chosen over the Black player and that happens,” Moss said. “But it also proves that you have to fight for everything one step harder than the other athletes that may be around you.”

Although there were no American-born Black players in the series, Houston Astros manager Dusty Baker became the third Black manager to win a World Series behind Dave Roberts and Cito Gaston.

“It was a little disappointing for that to be brought to our attention, but we did have an African American manager who actually won the World Series, and I think that’s something to hang our hat on,” Hawkins said. “It’s usually not an African American manager, and you have African American players. Hopefully, at some point in the future, we can get to where we have an African American manager and African American players participating in the Fall Classic.”

What’s next?

The sport that is widely known as America’s pastime still struggles to expand diversity and reach new audiences. Targeting the younger generation is the first step.

For Todd, the best way to appeal to the current generation is by setting the standard.

“When you want to play that sport, you want to be that guy, right? You have Michael Jordan, LeBron James, Kobe, you know, we all trended in a different direction,” Todd said. “Once you have that idol, once you have that guy that’s bringing you back into the sport – that’s what gets the attention.”

While there are a slew of NBA greats who have altered the sports landscape for the better on the national stage, finding Black MLB icons will be crucial toward bridging the gap between the sport and the community. Current baseball superstars Mookie Betts, Andrew McCutchen and Aaron Judge are strong role models, but many believe the sport is hurting for more.

While developing more Black icons is the goal, bridging the gap between travel baseball and high school leagues could become the priority. Programs like the DREAM Series, the Hank Aaron Invitational and the Breakthrough Series are key to getting that 7% number up in the future with more and more minority children struggling to have the resources they need to be noticed.

“That’s huge for the kids in those areas that they have access to these programs,” former major leaguer and DREAM Series coach Lou Collier said. “But I think there’s so much more that can be done, that we can reach out to many more kids that are playing the game, that love the game, that can create opportunities for their families and for themselves. And, for future generations.”

There is a long road ahead, but the continued efforts toward more inclusivity have been well established, and young stars like Todd and Moss are creating change by example, one base at a time.

“We are just breaking down barriers within baseball itself,” Todd said. “Like I said, I love what we’re doing. I think as we can move forward and continue to see different faces in different positions, we’re more open to it. Just giving African Americans or whoever it might be their chance and just believing them. That’s what’s important.”