PHOENIX – The Hia-Ced O’odham people were known for their nomadic lifestyle in the parched Sonoran Desert, and the “Sand People” often were on the move in search of water sources, surviving in the harshest of terrains.

But lack of water wasn’t the biggest threat to the Hia-Ced. In the mid-1800s, yellow fever swept through their ancestral lands, which lie on both sides of the U.S. and Mexico border, and wiped out much of the population.

According to descendants, only four Hia-Ced families survived – those who had fled to neighboring O’odham land to escape the epidemic. Because their land was no longer inhabited, early American settlers believed the Hia-Ced had died out.

Today, the number of Hia-Ced is about 1,000. An exact count is difficult to determine because census forms don’t recognize a Hia-Ced tribe.

In Arizona, 22 federally recognized tribes inhabit nearly every region of the state, according to the Arizona State Museum, but the Hia-Ced isn’t one of them.

But some descendants of those four surviving families are working to change that. They’re researching the history of the Hia-Ced to prove their existence and distinctions, and working to advocate for recognition with the federal government.

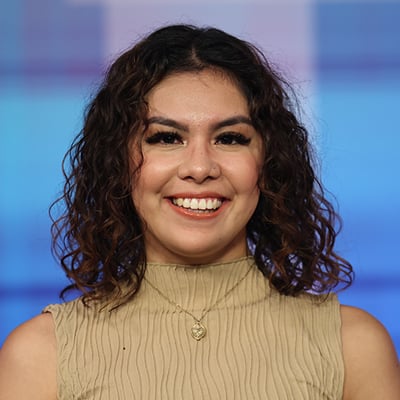

“It isn’t our fault that there was an epidemic that affected the Hia-Ced O’odham, but we still are a tribal community that deserves the federal recognition like every other tribal community here in Arizona,” said Lourdes “Lulu” Pereira, an Arizona State University student and official archivist for the Hia-Ced Hemajkam LLC, which was established in 2015 to work toward federal recognition and reclamation of ancestral lands.

Lourdes “Lulu” Pereira wears a Hia-Ced O’odham ribbon skirt with the tribe’s seal at the Hayden Library at ASU in Tempe on Dec. 1, 2022. (Photo by Campbell Wilmot/Cronkite News)

“I believe the foundation of this comes down to the responsibility of the federal government – acknowledging those tribal communities that they inflicted genocide on, that they have put through hell and through disturbing, horrific actions.”

The Hia-Ced Hemajkam LLC governing board, led by Pereira’s mother, Christina Andrews, has seven members, who meet monthly on their quest to become federally recognized.

Hia-Ced aboriginal territory spans the west side of what now is the Tohono O’odham Nation, west to Yuma, north to the Gila River and south to Puerto Peñasco, Mexico.

Andrews doesn’t think it will be possible to reclaim the entire land, so the LLC is focusing on taking back the national park sites in Hia-Ced territory: Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge.

For the Hia-Ced, these cultural lands are sacred.

Andrews has a clear message to the National Park Service: “You’re just a babysitter for us right now, and that’s fine. But we want to get our home back, and that’s our goal.”

The U.S Fish & Wildlife Service and NPS declined to comment for this story.

Complicated history with Tohono O’odham

The Hia-Ced had established a tribal home within the Tohono O’odham Nation, with whom they share the heritage O’odham language. But internal strife led to some of the Hia-Ced striking out on their own, opting instead to reclaim their primary heritage.

Otherwise known as the “Areneños” or “Sand People,” the Hia-Ced are cousins to the Akimel Oʼodham (River People) and the Tohono O’odham (Desert People).

Although the O’odhams share a common name, distinctions between the tribes vary in dialect, geographic location, migration patterns, housing type and food.

Andrews said the Tohono O’odham Nation sold the Hia-Ced aboriginal lands to the federal government for $26 million in 1976 as part of the Indian Land Claims Act – without the consent or knowledge of the Hia-Ced.

In 1984, the Tohono O’odham Nation unofficially adopted a Hia-Ced district as a part of their tribe. In 2013, the Hia-Ced officially became the 12th district of the Tohono O’odham Nation, led by Andrews as chairwoman, but the district dissolved two years later over disagreements regarding council decisions and district monetary budgets.

In an email, spokesperson Matt Smith said the office of Tohono O’odham Chairman Ned Norris Jr. isn’t aware of any official efforts being made by the Hia-Ced to become federally recognized.

Lorraine Eiler, who is Hia-Ced but remains a member of the Tohono O’odham Nation, said seeking federal recognition may not be in the Hia-Ced’s best interest.

Eiler led the effort to dissolve the 12th district, according to an article by ICT, a nonprofit news organization that covers Indigenous peoples.

“I think in some ways, you’re going to be jeopardizing individuals that don’t have the means to live on very limited income, to relinquish from the tribe and try to seek another federal recognition,” Eiler said, referring to the funding that accompanies federal recognition. “It’s going to be a hardship for them.”

Lorraine Eiler, a Hia-Ced O’odham woman, recalls growing up in Ajo, which is about 40 miles from the U.S. Mexico border and sacred Hia-Ced lands. Photo taken at in Ajo on Nov. 18, 2022. (Photo by Scianna Garcia/Cronkite News)

The path to federal recognition

An Indigenous community can become federally recognized in two ways: by an act of Congress or through the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

To become federally recognized through the BIA, the group seeking acknowledgment must submit a letter of intent to petition, then a documented petition including extensive evidence of the tribe’s past, according to bureau guidelines. The Hia-Ced are in the process of collecting and assembling documents that prove their existence through the years.

A tribe can also become recognized directly through Congress. Andrews has met with U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Tucson, in hopes of persuading him to introduce a bill that would federally recognize the Hia-Ced.

By becoming federally recognized, tribes “are eligible for funding and services from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, either directly or through contracts, grants, or compacts,” according to USA.gov. Cultural, historic and land preservation projects are among the benefits.

According to the BIA, federal recognition “acknowledges your tribe’s status as a government with independent sovereignty derived from your historical status as a tribe before European contact and maintenance of your government without break since then.”

Andrews said she wants the Hia-Ced to “have a voice at the table at the federal government level” and lamented the exclusion of the group in decisions regarding their sacred lands.

In 2020, the Trump administration waived regulations that would have prevented border wall construction on Hia-Ced aboriginal land.

Andrews said construction of the border wall in southern Arizona drained much of the water off Hia-Ced land and forced members to rebury three bodies from graves that had been disturbed.

A sacred human-made pond located in Quitobaquito Springs in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument also was affected by the border wall, which was built through the monument.

Andrews said educational and language barriers have prevented federal recognition of the tribe.

“(The federal government) made it seem like we were extinct, but we had no idea how to navigate in this Western world at that time when (our land) was taken away,” she said.

Eiler agreed that education, experience and money have been crucial factors holding the Hia-Ced back from landing federal recognition. She also said it’s because “they’ve always considered us O’odham.”

But many of the Hia-Ced want to be recognized separately from other O’odham nations and to reclaim their heritage in the eyes of the federal government.

“There’s no secret when it comes to the Hia-Ced and our distinction here in Arizona,” said Pereira, the ASU student. “We have sovereignty – we were always sovereign – which is why we thrived and survived for so long in various regions across this beautiful continent in Turtle Island (Earth).”