PHOENIX – In 2021, when the Phoenix Suns emerged from an 11-year playoff drought to unexpectedly reach the NBA Finals against the Milwaukee Bucks, they revived a fan base around the Valley that rallied around their Western Conference champions.

Every Finals game was met with anticipation as fans ready to root on Devin Booker, Chris Paul, Deandre Ayton and the rest of the Suns gathered at bars and restaurants around the Footprint Center, many flying large purple flags with various versions of the team’s logo on them, welcoming patrons to downtown Phoenix.

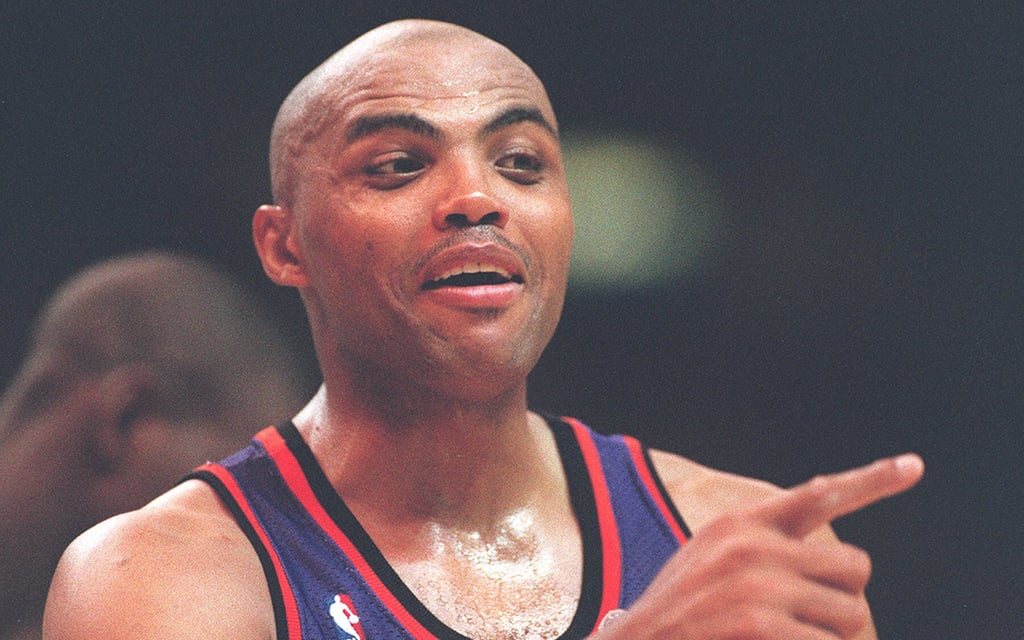

It was a buzz that brought the Valley together in a way that Phoenix fans hadn’t experienced for 30 years, since a Suns team led by Charles Barkley, Kevin Johnson and Tom Chambers captured the Valley’s imagination en route to the league’s best record and a berth in the NBA Finals against Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls dynasty.

“When the Phoenix Suns are rolling, this city is connected,” said Suns radio analyst Tim Kempton, a member of that 1992-93 team. “It’s the city and the state that wraps their (arms) around them.”

The impact of that 1992-93 Suns team went far beyond the basketball court, though. That team also marked the beginning of a downtown Phoenix renaissance that transformed the city.

And it is likely that none of it would have been possible without the vision of the team’s managing partner at the time, Jerry Colangelo.

Colangelo has had a basketball in his hands or nearby for most of his life. He was a star in baseball and basketball in high school while growing up in the “Hungry Hill” neighborhood of Chicago Heights, Illinois.

Several colleges came calling for him in both sports, and he eventually chose Kansas to play basketball alongside the great Wilt Chamberlain. However, when Chamberlain signed a pro contract with the Harlem Globetrotters, Colangelo decided to transfer to Illinois, to be near his hometown.

Following his playing career, Colangelo famously sold tuxedos and got involved in marketing, which led to an opportunity to remain connected to the sport he loved. In 1966, he was instrumental in the launch of the Chicago Bulls, working in the front office during the franchise’s first season in the NBA.

Following one season with the Bulls, Colangelo was approached by a group hoping to buy an expansion franchise as the NBA looked to continue its expansion.

That’s what introduced Colangelo to the Valley in 1968, and he still recalls his first impression as he awaited the arrival of his luggage at the single, outdoor baggage-claim area at Phoenix Sky Harbor airport’s only terminal at the time.

As was often the case with Colangelo, he saw only possibilities. He was 28 years old.

“When I first saw downtown Phoenix in 1968, it was pretty desolate,” Colangelo said. “But what I saw was an opportunity that someday, under the right circumstances, this could be a vibrant place.”

Shortly after Colangelo arrived, the city held a press conference for Colangelo to introduce himself and the Suns to the community. He told the media and the rest of the Valley, “this community owes us nothing. It’s up to us to earn the respect and support of the community by how we conduct ourselves on the court, and in the business community.”

Colangelo started as the general manager for the Suns and found early success. He was involved in multiple roles, even coaching the Suns in the second half of their second season. The team started that 1969-70 campaign 15-23, so Colangelo fired coach Johnny Kerr. He coached the team himself to a 24-20 record the rest of the way.

It was enough to get the Suns into the NBA playoffs for the first time. Six years later, with John McLeod coaching, the Suns shocked the league and defeated the defending-champion Golden State Warriors in the Western Conference finals to advance to the NBA Finals for the first time in franchise history.

Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum, nicknamed “The Madhouse on McDowell,” hosted the Phoenix Suns from 1968 to 1992. (Photo by Christian Petersen/Getty Images)

It would be another 17 years before they got back, when Barkley and company stormed through the regular season and beat Seattle in seven games in the Western Conference finals to advance to the NBA Finals.

Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum, dubbed “The Madhouse on McDowell” northwest of downtown at 19th Street and McDowell Road, rocked during those 1976 playoffs as players like guard Paul Westphal and rookie Alvan Adams, a passing wizard at the center position, captivated the Valley.

The Suns lost in six games to the Boston Celtics dynasty in an epic series, which included a triple-overtime Game 5 classic that is often referred to as “The Greatest Game Ever Played.”

That team, that series and that game established Phoenix as a Suns town.

“The first time the Suns went to the NBA Finals, it was a complete surprise,” said the Suns’ Hall of Fame broadcaster Al McCoy, who is in his 51st season as the voice of the team. “They didn’t have a big year and just barely had a record over .500.”

Through 13 years under McLeod, the Suns were perennial playoff contenders, but they were unable to break through in the playoffs to reach the Finals again. Through ups and downs, the team’s supporters followed them every step of the way.

Then a drug scandal rocked the franchise in 1987. Several current and former players were indicted on charges related to a cocaine-trafficking ring.

It was seen as a disaster for the franchise and the NBA.

Colangelo saw only possibilities.

Amid rumors that the club’s owners might sell the team and that the city could lose it, Colangelo was rounding up investors to buy it. When his group purchased the team and Colangelo took charge as the managing partner, he and his partners were questioned for paying a then-NBA record $44.5 million for the team.

Colangelo immediately brought in former Suns coach Cotton Fitzsimmons to serve in the front office, and the two brokered a trade that sent Larry Nance – the club’s most popular player and only tradeable asset – to Cleveland in a deal that would bring point guard Kevin Johnson from the Cavaliers along with center Mark West and other players, and the first-round pick the team would use to draft Dan Majerle.

It was a blockbuster deal that remade the franchise, and the Suns would follow it in the offseason by signing the NBA’s first unrestricted free agent, forward Tom Chambers. Fitzsimmons would move from the front office to the bench to coach a high-powered, up-tempo style that was a perfect fit for the team’s personnel.

After taking control of the team, Colangelo started to look at downtown Phoenix as a potential site for a new arena, believing that it would revitalize the city’s dormant core.

“I believed in my heart of hearts that if we put an arena downtown, that could be one of the real factors to make this thing (downtown) turn around,” Colangelo said.

While the Phoenix Convention Center was downtown, along with a few major hotel chains and several corporations and banks that housed their Arizona operations there, the area went largely dark after the close of business.

There was little to no nightlife to attract residents from around the Valley, or attract visitors from out of town.

“Downtown was kind of a ghost town in the ’90s,” said Jon Talton, a former reporter and columnist at The Arizona Republic and a Phoenix historian. “It was strictly business. When lawyers, bankers and businessmen got off work, they all returned home, leaving downtown deserted.”

Economically, the city was also struggling. Phoenix found itself in a financial crisis, both in the housing market and from a lack of business income. Multiple Phoenix businesses left the Valley in pursuit of better opportunities elsewhere. Meanwhile, the Valley’s population was rapidly increasing as surrounding communities such as Scottsdale, Mesa and Chandler boomed.

There was some pushback by the public about building a new arena. Some Valley residents opposed using taxpayer money to construct an arena. Fans also didn’t want to move out of the iconic “Madhouse.” Colangelo pitched his arena plan as a “public-private“ project, and it ultimately was approved.

“A lot of people thought that Colangelo was getting a sweet deal and taxpayer money for sports,” Talton said. “But it has worked out remarkably well.”

The $89 million, state-of-the-art arena on Jefferson Street was designed to be an intimate basketball venue, with sightlines specifically drawn up to give fans the best view of the court, and the facility included a practice court for the team.

America West Arena opened on June 6, 1992, with a George Strait concert. Colangelo, who had an office in the arena, remembers the flock of people who attended.

“I’m watching people walk the streets of downtown Phoenix coming to the arena,” Colangelo said. “It was very exciting for me to see it actually happening and unfolding.”

There was just one piece missing from the new building – a superstar.

Before the 1992-93 season, the Suns had made three straight playoff appearances, but could never get beyond the Western Conference finals.

“We felt we did have a competitive team,” Colangelo said. “We just couldn’t get over the hump. We felt we needed a star.”

As the Suns walked off the court in Portland after falling to the Trail Blazers in the 1992 Western Conference finals, assistant coach Lionel Hollins famously lamented, “We need to get ourselves a Charles Barkley.”

Colangelo went one better. He went and got the Charles Barkley.

Just 11 days after that George Strait concert, the Suns announced another blockbuster, this one a trade that sent three players, including fan favorite Jeff Hornacek, to the Philadelphia 76ers for Barkley, the dynamic, bombastic power forward.

“It just so happened Charles was going through his own situation in Philadelphia, and the circumstances lent themselves to the possibility that they were willing to move him,” Colangelo said. “We took Charles because we felt he could be the difference between playoffs and championship.”

Shortly after the trade, Colangelo traveled with the U.S. men’s national basketball team to watch the Olympics in Barcelona, Spain. It marked the first time NBA players rather than college stars were allowed to represent their country in the Olympics. The 1992 “Dream Team” is considered to be the greatest team ever assembled, with 11 eventual Hall of Famers, including legends such as Magic Johnson, Larry Bird, Michael Jordan.

And Barkley.

As the Dream Team dominated the Games and the headlines, Barkley stood out even among the NBA’s biggest stars. And back in the Valley, the anticipation for the team’s Silver Anniversary season grew.

Meanwhile, Fitzsimmons announced that he would move back to the front office and take over as the team’s broadcast analyst with his hand-picked successor, assistant Paul Westphal, taking over as head coach.

The team would enter 1992-93 with a new arena, a new coach, a new superstar and unprecedented interest from fans.

The Phoenix Suns traded for Charles Barkley in June 1992, believing the NBA superstar would push the team from playoff contender to NBA champions. (Photo By Michael Macor/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

The 19,023 season tickets available at America West Arena were sold out before a single game was played there. Another 5,000 put their names on a waiting list for season tickets. The team also sold out its entire inventory of advertising signage in the building.

In their first season together, the existing Suns stars aligned with the new one, and the Suns thrived. They won 62 games, a franchise record that stood until 2021-22. It was the best record in the NBA and gave the Suns homecourt advantage throughout the playoffs.

Downtown Phoenix became a destination when the Suns were playing at home, and the team generated more revenue than any team in the NBA, including teams in major markets such as Los Angeles and New York, a feat Colangelo called the franchise’s “star moment.”

Barkley was named the NBA’s Most Valuable Player, the first player in a Suns uniform to win the award.

“I have never had the pleasure of broadcasting an individual like Charles,” said McCoy, the Suns’ play-by-play voice. “He was a player who just would not give up. I don’t think there’s ever been a Suns player that had more desire to win than Barkley.”

Yet, the Suns nearly stumbled at the start of the Western Conference playoffs. They fell behind 2-0 – losing both games at home – in a best-of-five series against their nemesis, the Los Angeles Lakers.

After the loss, Westphal issued his now-famous “guarantee” that the Suns would beat the Lakers in the series.

“We’re going to win the series,” Westphal said. “We’re going to win one Tuesday, and the next game’s Thursday. We’re going to win there, and then we’re going to come back and we will win the series on Sunday. And everybody will say what a great series it was.”

That’s just what the Suns would do, holding on in overtime to win Game 5 as the America West Arena crowd chanted, “Beat LA!”

The series comeback, combined with Westphal’s confident prediction took the excitement around the team to a new level as the team advanced through a series against San Antonio and then the Seattle SuperSonics.

“The community was already enhanced with the Suns and big-time followers of the Suns,” Colangelo said. “This one was the icing on the cake with the additions of Barkley and the new building. The excitement downtown was unbelievable.”

However, one major obstacle remained. The Chicago Bulls, with a roster constructed by one of Colangelo’s former scouts, Bulls General Manager Jerry Krause, and led by Michael Jordan, was in pursuit of a third straight championship.

As they had against the Lakers, the Suns lost the first two games of the best-of-seven series at home. They won Game 3 in triple overtime at Chicago Stadium, only the second triple OT game in Finals history with both involving the Suns. This time, Westphal told the media after the victory, “The good guys won.”

The Suns fell in Game 4, and Chicago officials asked fans not to cause damage if, as they anticipated, the Bulls closed out the series in Game 5.

Barkley and Westphal seized upon the warning and Barkley erased the scouting report written on a whiteboard in the Chicago Stadium visitor locker room, replacing it with the message: “Save the City.”

Behind that rallying cry, the Suns forced a Game 6 at America West Arena. A Phoenix win would send the series to a Game 7 in Phoenix. Instead, Jordan scored 33 points and the Bulls limited Barkley to 21 points and Chicago’s John Paxson hit a three-point shot with 3.9 seconds to play, ending the team’s date with destiny.

Despite the loss, the Suns brought a city together.

Since the Phoenix Suns moved to Jefferson Street before the 1992-93 NBA season, downtown Phoenix has transformed into an easily accessible hot spot in the Valley thanks in part to a light rail system that connects Mesa, Tempe and Phoenix. (Photo by Christian Petersen/Getty Images)

“The Finals in the ’90s were galvanizing for the city,” Talton said. “The Cardinals were playing at Sun Devil Stadium, and we didn’t have a major league team or a hockey team. The Suns were still the city’s team.”

For maybe the first time, a city staged a victory parade and rally for a team that didn’t actually come away with a championship. But Colangelo wanted to honor the team and its fans after a memorable season.

Colangelo watched what he called the “love-fest” from a balcony outside his office that overlooked America West Arena’s plaza at the time. He and Suns players and coaches addressed about 300,000 fans who jammed into downtown Phoenix on a 106-degree June day to celebrate.

It is a moment Colangelo still looks back upon today.

“I remember that like it was almost yesterday,” Colangelo said. “I was on the balcony in my office at the arena, and you looked out and all you saw was purple and orange on a hot day. It was just amazing.”

The success of that 1992-93 team, and the enthusiasm that fans brought to the new downtown arena only made Colangelo see more possibilities.

Despite limitations that America West Arena presented for hockey because of the basketball sightlines, Colangelo helped the Winnipeg Jets relocate to the Valley as the Phoenix Coyotes in 1996-97.

The Coyotes would eventually depart for their own new arena in Glendale, an experiment that ultimately failed there.

Then Colangelo was approached by Major League Baseball, which hoped to expand into the southwest. Colangelo again went to work to bring together a group of investors and launch a stadium project. Again, he targeted downtown Phoenix to continue the revitalization of the city’s central core.

In 1995, Colangelo announced that his group had been awarded a major league franchise, and the Arizona Diamondbacks were born. “Bank One Ballpark” would also be constructed along Jefferson Street just east of America West, giving downtown Phoenix a designated “sports” district.

In 1998, the Diamondbacks made their debut, and in just four years the team reached the World Series, where Arizona upset the New York Yankees in an epic seven-game series. It was the quickest an expansion team had ever turned around and won a championship in the history of MLB, and it remains the only major sports championship in Valley history.

“I remember on the night that we won it, I said, ‘Lord, you have a funny sense of humor,’” Colangelo said, laughing. “I waited my whole life for an NBA championship and it did not happen. Yet here we are, going to win a World Series.”

With the Coyotes, Suns and Diamondbacks all located within a block of each other on Jefferson for a time, the downtown area continued to boom. The Phoenix Convention Center was redesigned and expanded. New hotels, residences, bars, restaurants and even a grocery store popped up.

A light rail system was constructed, connecting Mesa, Tempe and Phoenix. Arizona State University added a downtown campus offering degrees in journalism, nursing and law near the Valley’s epicenter for these occupations.

“After that parade, all the people were basically in Washington Square Park out in front of the arena,” said Kempton. “That now is all high-rises, buildings, offices, restaurants, and living places. The unique thing is that it’s actually downtown Phoenix.”

It all started with the America West Arena project. The arena has undergone two major renovation projects since then, and under its new name – Footprint Center – it remains home to the Valley’s first major pro sports franchise, the Suns.

“Downtown Phoenix has evolved in response to sports,” McCoy said. “It has turned downtown Phoenix into a reality, with restaurants and things to do with all of the sporting events there. It certainly has been the catalyst to make downtown Phoenix something special. It created a reason to be in downtown Phoenix.”

Since 1995, jobs in the area have tripled as companies moved downtown. The economy recovered, as new projects and buildings in the city restored balance to the money supply.

“Colangelo was the major force behind the beginning of downtown’s revival, which you see today,” Talton said. “All of that began with what was America West Arena.”

In 2004, Colangelo sold the Suns for almost 10 times what he and his partners paid for the franchise. Only months after the sale, he was forced out of his role as managing general partner of the Diamondbacks.

Still, he remained involved in sports as director of USA Basketball and chairman of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. He also helped revive Grand Canyon University and its sports programs.

There remains work to be done in the Valley, and Colangelo plans to continue to help.

He sees only possibilities.

“When I first came to Phoenix in 1968, there were 700,000 in the entire Metro area,” he said. “Today, there are over five million. In my mind, I want people living downtown, working downtown and enjoying all the facilities that are there downtown. You don’t have to go very far. You could get it all there.”