Aiden Wander poses with his family at Arete Prep’s senior night, which marked his final high school football game. (Photo by Michele Aerin/Cronkite News)

GILBERT – The football flew past Arete Prep high school’s quarterback’s hands, and Arete Prep running back Aiden Wander saw his chance to make a play early in the season against Miami. He dove for the ball, but the rest of the story is fuzzy.

Wander doesn’t remember what side of the field the play occurred, barely recalling what happened later that on that night in September. The ensuing two hours of ambulances, trainer’s tables and X-ray machines are patchy and incomplete.

That is because someone else had the same idea and dove for football. In the dive, the two players collided, leaving Wander with a severe concussion.

Despite the injury, Aiden returned to playing football before the end of the season. He wanted to come back and finish out his season, determined to not let the injury end his senior year early.

Wander’s father, Jeremy, is Arete Prep’s assistant head coach and watched as his son struggled to gain balance and bounce back that fateful night.

“Watching him get up, I started to suspect something was wrong,” Jeremy said. “He was reaching out for one of his teammates, and I couldn’t tell if he was reaching for his teammate to tell him, ‘No, I’m OK,’ (but) from talking to him later it turns out he was reaching out to his teammate to say, ‘Help me out.’”

As a parent and football coach, Jeremy has seen Aiden take his fair share of hard hits. Previously, Aiden dusted himself off and popped back up. Aiden staying on the ground, unable to walk off the field, was a new experience for both of them.

An ambulance escorted him to a nearby hospital in a neck brace so he couldn’t move his neck around to see. The majority of Aiden’s memory of the night stems from when he was waiting to be discharged from the hospital.

For the most part, Aiden doesn’t remember how he felt that night. But his persistent fear had more to do with not being able to finish his season with the team than his injury.

“I can’t really remember how I was feeling exactly,” Aiden said. “I am sure I was (scared) immediately after the hit. I was afraid (the doctors) would say I couldn’t play for the seven weeks we had left because it takes a varying amount of time to recover from a concussion.”

The recovery process wasn’t easy. Concussion symptoms can persist anywhere from weeks to months. Aiden also has ADHD, which made the recovery process more difficult.

“We saw the symptoms actually got quite a bit worse,” Jeremy said. “The inability to focus, it was definitely made worse by the concussion because before we could tell him, ‘Hey, you need to focus on this, you need to zero in.’ This was a lot more difficult for him to really sharpen the focus on it.”

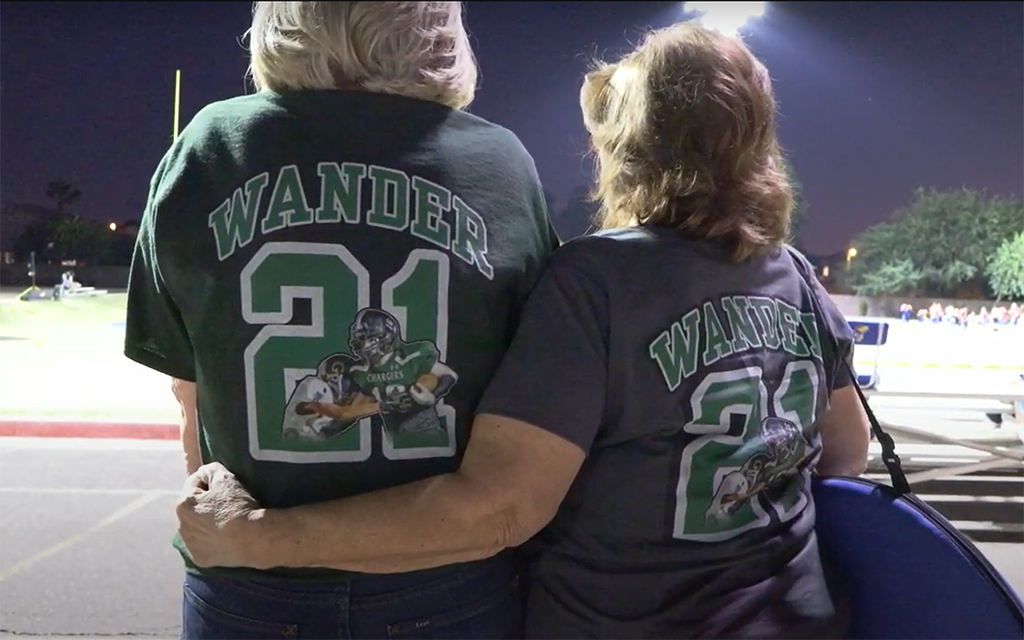

Aiden Wander’s grandmother, left, and mother show support for Aiden Wander at Arete Prep’s senior night with personalized T-shirts. (Photo by Michele Aerin/Cronkite News)

Aiden said that despite the recovery process and the symptoms of the injury, not playing again never crossed his mind. Getting back to the gridiron had always been his top priority.

“I knew pads are for protection, if someone hits my shoulder pads it’s going to protect my body. If someone hits my helmet it’s going to protect my head, and it did protect my head,” Aiden said. “(Contact is) kind of guaranteed in the sport, and I knew that it could happen at some point. It didn’t take away from my love of the sport or the desire to play the sport.”

While the helmet protected Aiden from a severe or fatal injury, parents, players and coaches are always looking to add more protection to the head area. The rise in understanding of chronic traumatic encephalopathy — a disease caused by concussions — has led to greater research into how concussions work and happen.

The findings also have inspired the company Guardian Caps to make soft-shelled caps that attach on top of a football helmet, which adds an extra layer of soft padding that reduces the force upon impact on collisions with a helmet. The caps are designed with elastic straps that allow more glide, so some of the force behind the collision slides away instead of a straight-on hit.

“Our standard model, it’s about 7 ounces of material, it’s just this closed cell foam, it won’t pick up any weight if it rains or in the wash or anything like that,” GuardianSports salesman Tony Plagman said. “The key is our straps slide through the facemask and they’re elastic, so there’s some give.”

Guardian Caps are used throughout the amateur, college and professional ranks of the contact sport. Initially sold to high school football programs, college programs including the University of South Carolina and Clemson began using Guardian Caps for offseason programs in 2013.

“Now over 250 colleges use the guardian caps,” Plagman said. “2,500 to 3,000 high schools use them, and about 30 percent of Arizona high schools.”

The NFL mandated that all linemen, tight ends and linebackers wear the Guardian Caps during training camp in 2022, and the number of concussions among those wearing the caps fell by over 50 percent, according to the league.

The caps are only used for practice or offseason activities, but eventually being able to implement them in games “is the goal” for Plagman and Guardian Caps.

Aiden, determined to come back and play, returned to the field for the final two games of the season, including his senior night. Despite the injury, there was never a doubt as to if he would come back at some point.

“(Getting hit is) kinda guaranteed in the sport, and I knew that it could happen at some point; something like that has happened before,” Aiden said. “I have been injured and that’s what a contact sport is for, so it didn’t take away from my love of the sport or the desire to play the sport. It was scary, but didn’t change (my love) at all.”

Michele Aerin contributed to the reporting of this story.