PHOENIX – Thousands of Afghan refugees who have come to the United States to escape the Taliban over the past two decades struggle with day-to-day tasks like finding jobs, opening bank accounts and getting driver’s licenses.

Of particular concern to many is their parolee status, which allows them to remain in the U.S. for no more than two years. But bipartisan legislation introduced in August in Congress would grant Afghan refugees permanent legal status, allowing them to avoid the lengthy asylum process and possible deportation.

In August 2021, the final American forces withdrew from Kabul, ending the longest war in U.S. history. But Afghans have been seeking better lives in America since the U.S. invaded their country to root out Osama bin Laden in October 2001.

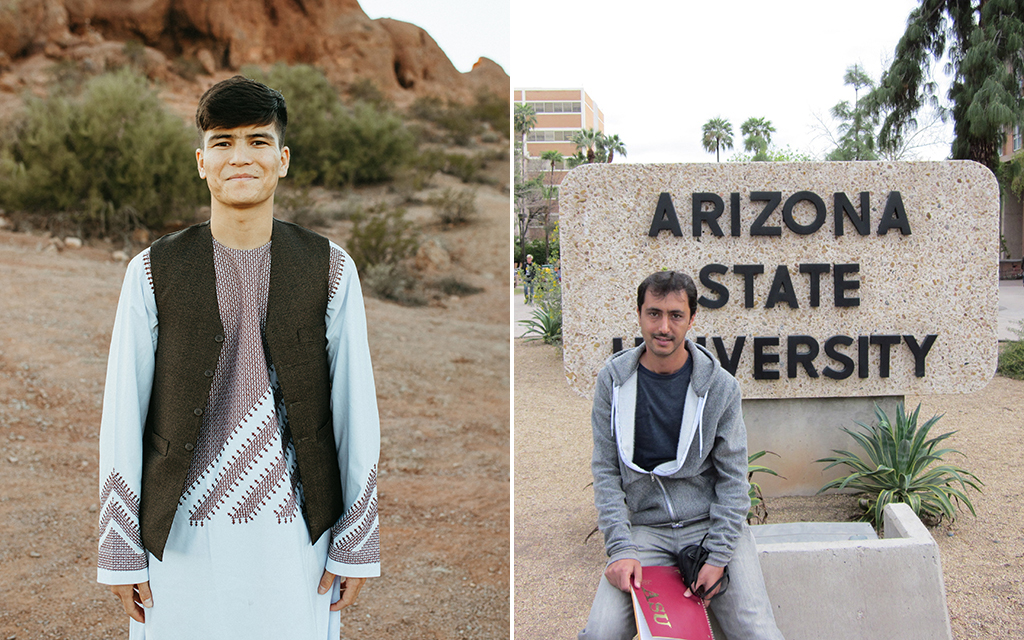

Teen struggles after father is kidnapped

Ali left his family in Afghanistan before he was a teenager. He traveled to India, Malaysia and Indonesia before finding his home Arizona. The date of this photo is unknown. (Photo courtesy of Ali)

“Finding jobs here is different … like putting in a direct deposit and like tracking all of those,” said Ali, 18, an Arizona State University student from Afghanistan. He said new refugees struggle with understanding job benefits, dealing with spam mail and, in some cases, even using a microwave.

To protect Ali and his family, Cronkite News is only using his middle name. He fled Afghanistan at 11, leaving behind his mom and four siblings and traveling with another family and a human smuggler to at least three countries before he landed in the U.S. at 15.

His father owned a shop in Afghanistan where Ali worked every day after school. His father chose to sell groceries to American soldiers and Afghan police, which angered the Taliban.

“The Taliban did not like this,” Ali recalled. “They warned us one time, ‘Do not sell this stuff to people, to the police, like American soldiers’ … my father did not listen to that.”

When his father went missing one day, Ali’s family searched for months in vain. Then a neighbor informed Ali the Taliban had kidnapped his father, and because Ali worked in his father’s shop, the Taliban was looking for him, too.

Ali said life “is not really that important over there,” and he was scared a similar fate would befall him.

“So my mom sent me with one of my relatives to Kabul,” Ali said. “Everything that my mom had, she sacrificed for me. She saved me.”

He spent the next few years in India, Malaysia and Indonesia, where he lived in an orphanage. His mom and siblings remained in Afghanistan, and he felt alone.

“It’s been challenging for me, mostly growing up, like how to cook for myself and how to wash my clothing,” Ali said. In 2018, Ali came to the United States as part of the Unaccompanied Refugee Minors Program, and a foster family in Arizona took him in. The program, run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, provides refugee foster care services for qualifying children who have no parent or guardian to care for them.

Diplomat here under temporary status

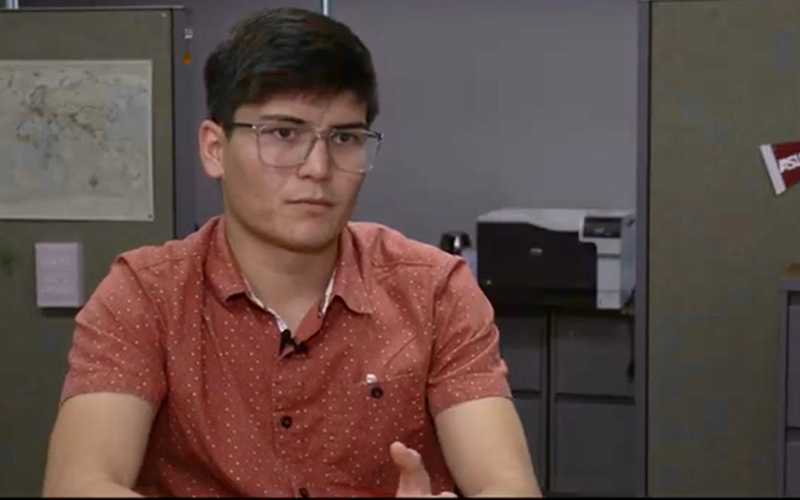

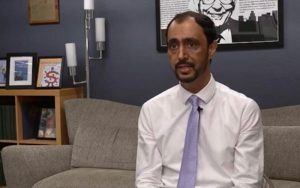

Javid Qaem, a professor of practice at ASU’s Watts College of Public Service and Community Solutions, arrived in the United States in January 2022 under parolee status.

When the U.S. pulled out of Afghanistan in August last year, Qaem, an ASU alumnus, was the Afghani ambassador to China.

“For four weeks, we were just crying. We didn’t know what really happened,” he recalled.

Qaem held the title of ambassador to China but no longer had a government to report to and said going back to Afghanistan “was not an option because there was a fear, there were also these revenge and target killings still going on.”

The U.S. Embassy in China helped him and his team find refuge in the United States. Qaem sent an email to his alma mater looking for a job, and “they took care of its own alum.”

Qaem called himself one of the luckiest because other refugees’ experience has not been that smooth.

“It’s very difficult for my family; they’re still adjusting. My wife, my kids, it’s a shock for them,” he said. “For my colleagues that came, it’s difficult. It’s been seven, eight months, nine months now. Many of them … don’t even have jobs.”

Act would grant permanent status

Under U.S. immigration law, someone who’s ineligible to enter the U.S. as a refugee, immigrant or non-immigrant may be “paroled” into the country by the secretary of Homeland Security. The provision is only used for emergency, humanitarian and public interest reasons.

Parolee status is especially stressful for refugees, said Nerja Sumic, the national field manager for We Are All America, a national campaign created in 2017 to help asylum seekers and refugees in danger. The temporary status allows them to stay only for 18 to 24 months, she said.

Many people under the parolee status, if they were to “ step foot on Afghanistan soil, they will be automatically killed,” said Sumic, who’s lobbying for passage of the Afghan Adjustment Act.

“It would give them permanent status here; otherwise, they will have to go through the asylum process and seeking asylum if their asylum cases are approved,” she said.

Javid Qaem emailed Arizona State University seeking a job, and they responded with an offer to teach. He’s grateful to the university for taking care of its alumni. (Photo by Alexia Stanbridge/Cronkite News)

Rep. Greg Stanton, D-Phoenix, was among those who introduced the bipartisan, bicameral legislation in August.

“We have a moral obligation to provide refuge to our Afghan partners who put their lives at risk to protect American troops. They shouldn’t be left in legal limbo, not while Congress has the power to grant them security and safety,” Stanton said in a press release in August.

Both Ali and Qaem support the bill.

“All of us want to go back. It’s just you can’t live there anymore,” Qaem said.

Ali doesn’t have to worry about his own status, but Sumic said his family would be helped if the act becomes law. Ali said he misses his mom and applied for his family to come to the U.S. but is still waiting to hear back.

Ali’s goal is “to be able to support them and … to help bring them here and reunite with them.”