WASHINGTON – When NASA smashes a spacecraft into an asteroid Monday evening to test whether it’s possible to deflect a future killer asteroid, several Arizona scientists will be watching.

“Planetary defense has been a growing field over the last couple of decades really,” said Cristina Thomas, a Northern Arizona University professor who will lead worldwide coordination of observations of the impact of DART – the Double Asteroid Redirection Test.

Thomas is quick to point out that the targeted twin asteroids propose “absolutely no impact hazard to Earth. And we’re not impacting the primary body, so we’re changing the orbit around the sun so miniscule-y that we’re not introducing any additional risk to the planet.”

But, she said, the goal is to be ready if there ever is a threat.

“While the risk of sizable asteroid impact is relatively small, it’s still something that exists,” Thomas said.

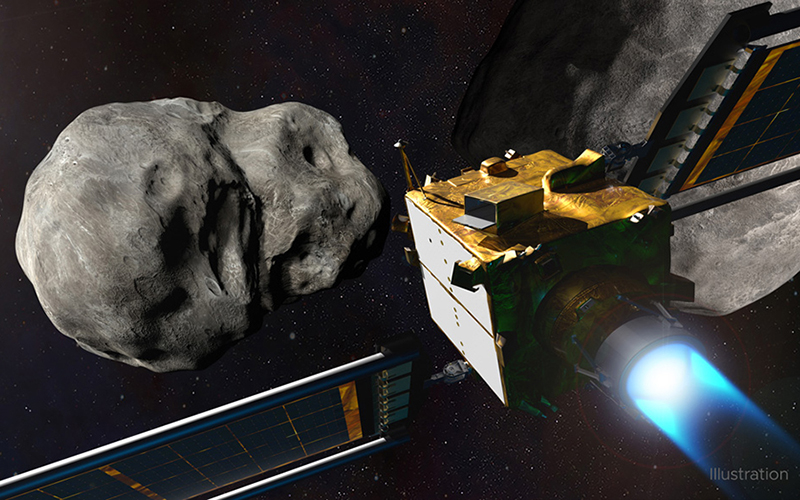

DART lifted off in November for a 6.8 million mile journey that will end in a collision with Dimorphos, a 530-foot moon of another, larger asteroid, Didymos. That journey is scheduled to end Monday at 4:14 p.m. Arizona time, when the spacecraft slams into Dimorphos at about 14,700 mph.

It is the first full-scale test of a kinetic impact technique that could be used in the future to strike an asteroid at high velocity. If everything goes according to plan, Dimorphos will be bumped ever so slightly out of its current orbit around Didymos.

NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft sets off Nov. 23 to collide with an asteroid in the world’s first full-scale planetary defense test mission. (Photo by Ed Whitman/NASA, Johns Hopkins APL)

University of Arizona’s Melissa Brucker will be among those looking to see if it worked. Researchers around the globe will be taking a series of images of the Didymos system when DART hits, looking for shifts in light patterns that indicate a shift in orbit.

“When you take many images in a row you can measure the brightness of it over time,” Brucker said. “And from that, we can see the brightness change as the moon moves behind and in front and to the side of the device, as they both are rotating.”

UArizona has another connection to the event: The university’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory found Didymos one night in April 1996, when Tucson’s Kitt Peak Observatory was a full-time discovery surveyor.

“There was a dot that was moving in three images, and that turned out to be what we now call Didymos,” said Brucker, who leads the Spacewatch program at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

She said the change in brightness will be too small for people to see – even if they could see it from Arizona. The DART crash will not be visible in the northern hemisphere at the time of impact, but several observatories in the southern hemisphere plan to be watching the impact.

People on Earth will receive news of DART’s impact about 38 seconds after it occurs, according to John Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. The event will be livestreamed on NASA TV from a camera aboard the NASA satellite.

Researchers will analyze photographs and data from the project to assess how to best apply it to future planetary defense scenarios, as well as how accurate the computer models are and how well they reflect the behavior of a real asteroid, NASA officials said.

Thomas recently became principal investigator for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology-Hawaii Near-Earth Object Spectroscopic Survey, searching for both potentially hazardous asteroids and other near-Earth objects that could come within 5 million miles of Earth’s orbit.

“We spent a lot of time thinking about the census of near-Earth objects, making sure that we understand where they are, how many there are, and discover them all,” Thomas said. “We know from that effort, that there is nothing incredibly large that poses a hazard to the planet.”

The practicalities of asteroid-hunting are not the only benefits likely to come from the mission, which has become “a great platform for testing, new navigation and solar panel technologies,” said Rhonda Stroud, director of Arizona State University’s Buseck Center for Meteorite Studies.

“Because this is a short time-scale mission, it was possible to put things on it – pieces of equipment – that were too new, too risky to use on bigger missions, but could really help in the future,” Stroud said.

Stroud, an expert in materials physics and planetary science, said the exact makeup of Dimorphos is not known, but DART could help answer that question and possibly allow comparison with some of the 2,000 different meteorites at the Buseck Center.

“If we could connect the type of asteroid that Didymos is to the meteorites in our collection … and if we had a sample in our collection that really represented the asteroid, that would be important,” Stroud said.

One of those questions is “whether Dimorphos is really a chunk off of Didymos” or if it is a piece of another asteroid that was simply captured in the larger asteroid’s orbit, they said.

“There are all kinds of benefits to this mission, and more than just playing bumper cars with asteroids,” Stroud said.