PHOENIX – A new ban on books containing sexual content makes its way into Arizona public schools this week, and critics worry self-censoring will add further stress to already overburdened teachers.

“We’re very concerned about the impact that this … would have on teachers and students who are trying to access new materials that reflect their perspective, but also materials that have been utilized in classrooms for a long time,” said Gaelle Esposito, an Arizona lobbyist working on education policy, LGBTQ+ rights and other progressive issues.

“It’s unclear what the consequences are for a teacher that violates the statute and what they may face. There are still concerns that because of the vague language, it’s going to have a chilling effect on teachers and libraries, for the books that they’ll carry on their shelves.”

House Bill 2495, signed into law by Gov. Doug Ducey in July, prohibits public schools from using any materials – text, audio or visual – that include descriptions of “sexual conduct,” “sexual excitement,” of “ultimate sex acts.”

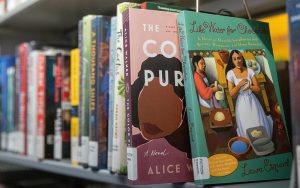

Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple” and Laura Esquivel’s “Like Water for Chocolate” are among the books that could be prohibited under Arizona’s ban on sexually explicit materials in schools. (Photo by Emily Mai/Cronkite News)

The law allows exceptions for material that has “serious” educational, literary, artistic, political or scientific value. But even then, parental consent is required for each book or work to be shared with students. If parental consent is not given, schools must provide an alternative assignment for that parent’s child.

The bill’s sponsor, state Rep. Jake Hoffman, R-Queen Creek, argues it’s not about banning books at all.

“The bottom line is this bill is about protecting kids from sexually explicit material,” Hoffman told the Senate Education Committee in March, adding that it doesn’t prohibit teaching anatomy or biology.

“We need them learning math, reading, writing and other incredibly important educational materials that will help prepare them for a vibrant and prosperous future, not worrying about sexually explicit material.”

Hoffman did not respond to Cronkite News’ requests for comment.

The law takes effect Saturday, but it remains unclear how it will work in practice – who will patrol materials and reach out to parents, for example. And teachers’ advocates worry about the broader effects on stressed-out educators.

Jeanne Casteen, executive director of Secular AZ and a former English, arts and literature teacher, said the restrictions will exacerbate the state’s teacher retention problem because educators are “finding the working and learning conditions in Arizona to be untenable.”

“In Arizona, we are chasing teachers out of the profession,” she said. “We’re training them here and then exporting our best and brightest to other states because we continually treat teachers as if they aren’t the content experts that they are.”

Lobbyist Gaelle Esposito is among those opposed to Arizona’s new ban on using materials with sexual content in schools. “This shouldn’t be something that the state Legislature or the federal government should be engaging in. Once the government steps in and tries to say, ‘We value this material over this material,’ it can become really dangerous,” Esposito says. (Photo by Emily Mai/Cronkite News)

Officials with several Arizona school districts, including Mesa Public Schools, and the Arizona Department of Education did not immediately return messages seeking details on how the law will be enforced.

Book bans are on the rise nationally, according to the nonprofit PEN America, which works to advance literature and defend free expression. From July 2021 to June 2022, the organization tracked 2,532 instances of books being banned, affecting 1,648 unique titles.

Since June, more than 139 additional bans have been enacted, and educators who push back are facing consequences. One Oklahoma school teacher resigned after hanging a banned-books sign reading “Books the state doesn’t want you to read” over her classroom library.

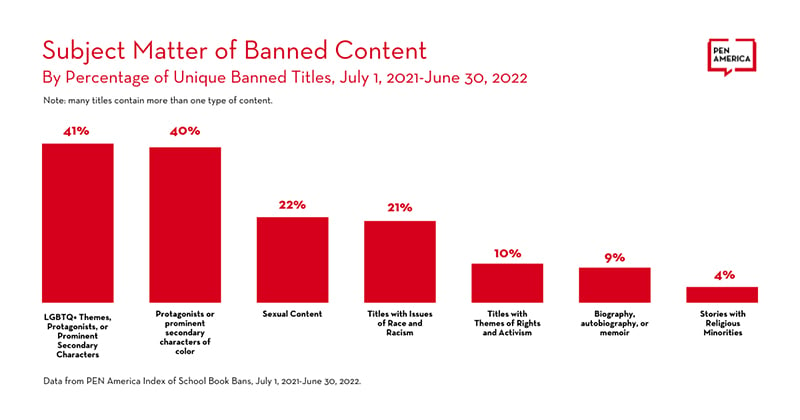

Of the books that have been challenged nationwide, 41% address LGBTQ+ themes, while 40% contain protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color, according to PEN America, leading some to believe censorship is at an all-time high.

Of the books that have been challenged nationwide, 41% address LGBTQ+ themes, while 40% contain protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color. (Graphic courtesy of PEN America)

Esposito, the Arizona lobbyist, noted that the original version of HB 2495 included a specific restriction on materials containing content related to homosexuality.

“That in and of itself shows the intent here,” she said. “They want to censor the discussion of diverse perspectives and use these extreme talking points to justify it.”

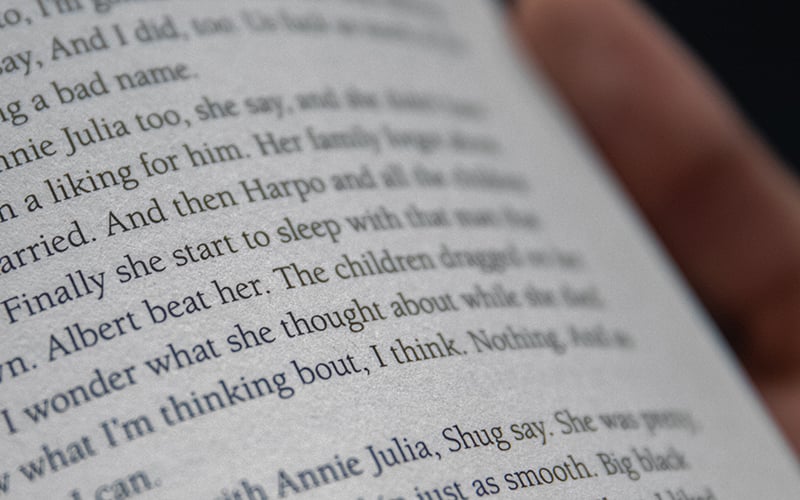

Casteen said titles that could be challenged include Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning story following the life journey of an African American girl who’s raped by her father, and Laura Esquivel’s “Like Water for Chocolate,” whose female characters are navigating their sexuality.

Casteen said her students enjoy novels like these because they can relate to the characters.

“By sharing these with students, a novel where they can see themselves and empathize with the characters’ experience and situations, that’s when the magic really happens.”

When Casteen once assigned Maya Angelou’s “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,” some of her students realized they’d had experiences similar to the main character’s account of sexual assault and reached out to a trusting adult to get help.

Casteen calls the new Arizona law a “whitewashing of literature.”

“It’s not fair to our students of color or even our LGBTQ+ students because a lot of books written by LGBTQ+ authors would be out,” she said. “Those kids, as we know, have a much higher rate of self harm and suicide. Taking books away from those kids puts them at greater danger.

“Instead of focusing on the real problems that teachers, students and working class families face in Arizona, we are engaging in solving problems that do not exist.”

Book bans are on the rise nationally, according to the nonprofit PEN America. From July 2021 to June 2022, the organization tracked 2,532 instances of books being banned, affecting 1,648 unique titles. (Photo by Emily Mai/Cronkite News)