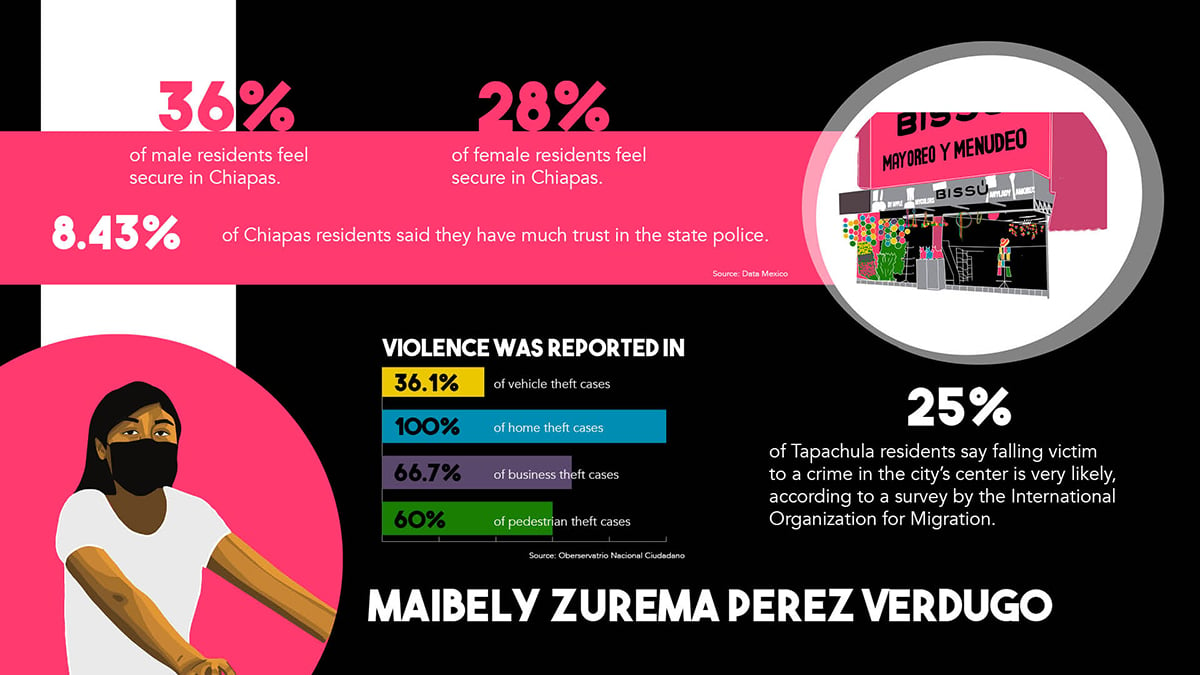

“It’s like the migrants are discriminated against a little bit,” Silva said.

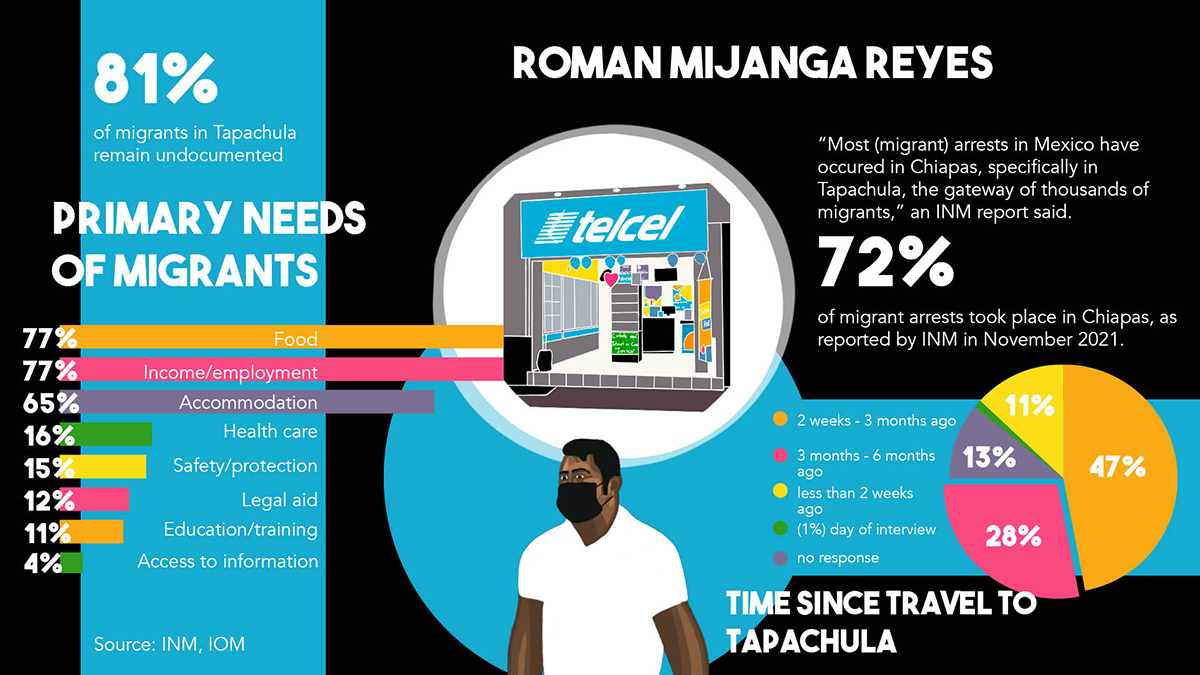

“There is more cultural shock here that we do not understand in aspects of language, culture and behavior,” Reyes said.

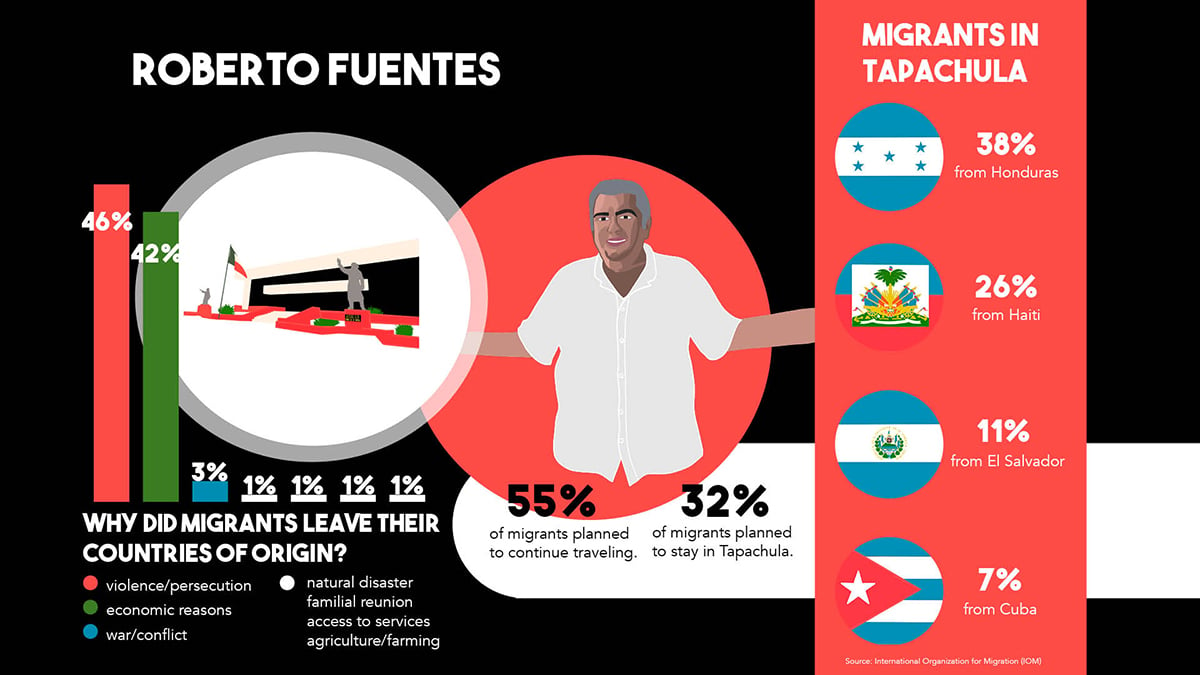

Fuentes said that the municipal government has provided the most assistance with lodging.

“We have our shelters and above all we focus on women and children who are more vulnerable,” he said.

Silva said that when migrants have issues, he doesn’t think they approach the government for help, but instead rely on human rights organizations and non-profit, non-governmental organizations.

“I don’t think it’s the government that has been supporting the migrants as much as it has been the NGOs,” Silva said. “When they suffer, they pick up the phone – not to call the government, but an authority on the outside.”

Silva said migrants worry that the government will not act or offer support.

Fuentes said that the government was “not equipped to receive” the migrants, but the situation still “has not gotten out of control.”

“We did not expect this,” Fuentes said. “Even so, there are stages where we have shown moments of crisis – there are sudden marches among migrants and there are events that block facilities – but they don’t go out of control.”

Fuentes said he hopes this crisis will bring Tapachula good in the long run.

“We are looking to lay the foundation so that it will be easier for the city to manage in the future,” he said. “We must be prepared to face them (migrants) in a better way in the future with the support of the state, federal and municipal efforts.”