WASHINGTON – The Supreme Court ruled Monday that inmates do not have a right to raise defenses in federal court that were rejected in state courts, denying the appeals of two Arizona death-row inmates in the process.

David Ramirez and Barry Jones, sentenced in separate killings, claimed that they were sentenced after poor representation at trial – followed by poor representation during their appeals that kept them from presenting evidence in their defense until they reached federal court.

Justice Clarence Thomas rejected the claim, writing for the 6-3 court that it would open the door to “wholesale relitigation” of state cases. But Justice Sonia Sotomayor said in a biting dissent that the majority’s ruling was “perverse” and “illogical” and would gut courts’ ability to protect “bedrock principle” of a defendant’s right to an attorney.

That was echoed by Robert Loeb, who represented Jones and Ramirez on appeal, and said in a statement that the decision means that federal courts will be helpless to offer any relief for those on death row even if evidence surfaces that they did not commit the crime.

“The decision misreads the federal statute, produces untenable results never envisioned by Congress, and amounts to an assault on basic fairness in the criminal justice system,” Loeb said. “I call on Congress to immediately fix the problem the Court has created today.”

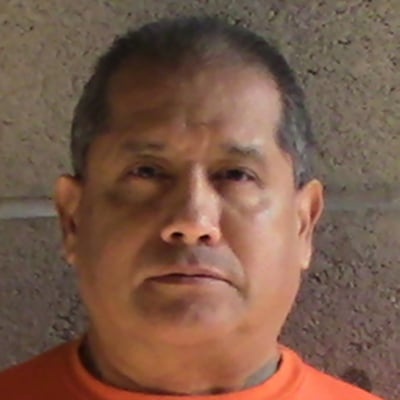

Barry Lee Jones has been on death row since 1995 for the sexual assault and murder in Tucson of his girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections)

Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich said of Ramirez and Jones, who have been on death row since 1990 and 1995, respectively, that the “wheels of justice take time to turn, but they should not be stuck for decades.”

“I applaud the Supreme Court’s decision because it will help refocus society on achieving justice for victims, instead of on endless delays that allow convicted killers to dodge accountability for their heinous crimes,” he said in a statement released by his office Monday.

Ramirez was convicted of the murders of his girlfriend and her 15-year-old daughter after repeatedly stabbing and slashing them in their Phoenix apartment in 1989. Thomas said police also found evidence that Ramirez had raped the daughter.

Jones was convicted for beating his girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter in May 1994 while she was in his care, including a blow to the abdomen that ruptured the intestine of the girl, who was pronounced dead when he took her to a Tucson hospital a day later.

In Arizona, defendants cannot claim ineffective assistance of counsel on direct appeal but have to make that argument in their state post-conviction review. But both Jones and Ramirez claimed that not only were their trial attorneys deficient, but so were the attorneys representing them in their post-conviction review, who failed to make the ineffective assistance of counsel at trial claim.

Normally, the issue could not be raised in federal court if it was not heard in state court, but both defendants cited a 2012 Supreme Court ruling, also in an Arizona case, that said federal courts could hear such evidence in exceptional cases.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed and ordered new hearings for both men on the ineffective counsel claims. It said Ramirez’s underlying trial-ineffective-assistance claim “was substantial,” and that in Jones’ case, “state postconviction counsel was ineffective for failing to develop the state-court record for Jones’ trial-ineffective-assistance claim.”

The state appealed to the Supreme Court, which said Monday that the circuit court got it wrong.

Thomas wrote that allowing the federal courts to engage in the fact finding that Jones and Ramirez want, would allow defendants to “sandbag” state courts by selectively presenting claims “‘while reserving others for federal habeas review’ should state proceedings come up short.”

“Such intervention is … an affront to the State and its citizens who returned a verdict of guilty after considering the evidence before them,” Thomas wrote. “Federal courts, years later, lack the competence and authority to relitigate a State’s criminal case.”

But Sotomayor wrote at length about the unqualified attorneys who represented Jones and Ramirez, adding that it was not until they were “at last represented by competent counsel” that they were able to raise their latest defense. She said the majority “understates, or ignores altogether, the gravity of the state systems’ failures in these two cases.”

David Ramirez has spent 32 years on Arizona’s death for the 1989 stabbing deaths of Mary Gortarez and her daughter, 15, in their Phoenix apartment. (Photo courtesy Arizona Department of Corrections)

“To put it bluntly: Two men whose trial attorneys did not provide even the bare minimum level of representation required by the Constitution may be executed because forces outside of their control prevented them from vindicating their constitutional right to counsel,” Sotomayor wrote.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 134 one-time death-row inmates have been exonerated in the U.S. since 1989, including eight in Arizona, based on factors such as false accusation, inadequate legal defense and official misconduct.

The Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry lists 112 inmates on death row. The state this month executed Clarence Dixon by lethal injection, the first execution by the state in eight years.

Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, said Jones’ and Ramirez’s cases “illustrate how serious Arizona’s problem is in providing competent lawyers to people on death row.”

“If Arizona is interested in fairness and if Arizona believes that everyone’s constitutional rights are important, it needs to make sure that the lawyers who are assigned to handle capital cases are competent and are provided the resources that are necessary to properly try a case,” Dunham said. “Otherwise, I don’t think the state can say with a straight face that the death penalty is an instrument of justice.”