WASHINGTON – As the child of visa-holding parents, Ayaan Siddiqui does not face deportation to India – yet.

But the BASIS Peoria senior, like an estimated 200,000 other “documented Dreamers” in the U.S., could be deported to a country he barely knows when he turns 21 and ages out of the protection of his parents’ visas.

“I have lived all my memorable life here. I think I am American, through and through,” the 17-year-old said Wednesday, as he joined lawmakers and other documented Dreamers on Capitol Hill to push for a bill that would protect them from being deported when they age out.

The America’s Cultivation of Hope and Inclusion for Long-term Dependents Raised and Educated Natively – or America’s CHILDREN – Act of 2021 would apply only to dependents of noncitizens who are in the U.S. on work visas.

The bill would let them apply for permanent legal status if they have been in the U.S. at least 10 years and have graduated from “an institution of higher education,” among other requirements. It would also grant work permits to successful applicants.

Without that protection, those young adults are supposed to self-deport after they turn 21, and then apply for readmission if they desire. For those already deported, the bill would allow them to return to the U.S. if they met certain requirements.

“I want to help the documented dreamers who are here today,” said Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., a co-sponsor of the Senate version of the bill.

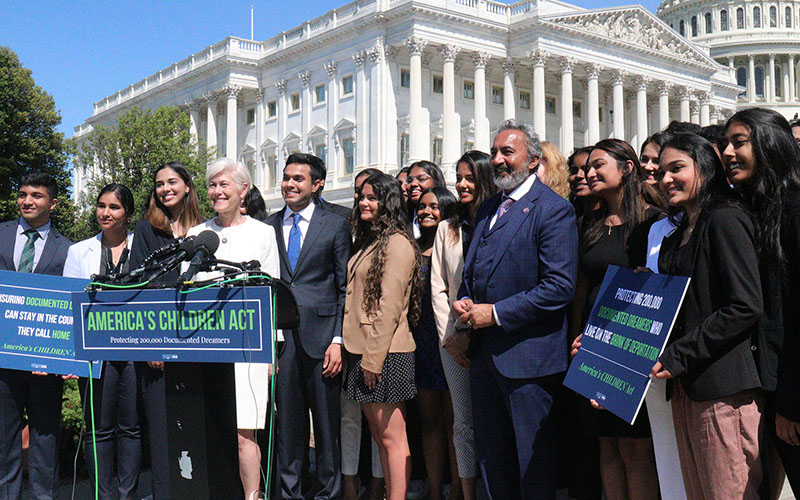

Ayaan Siddiqui, a senior at BASIS Peoria, was in Washington to lobby for passage of the America’s CHILDREN Act, which would protect a reported 200,000 people like him, noncitizens who were brought to this country by visa-holding parents, but who are in danger of losing that protection. (Photo by Elsa Hortareas/Cronkite News)

“Their parents came to the United States on legal visas but they are caught in the trap while their parents are waiting for green cards year after year after year, and they may reach that age of 21 where they technically can’t stay here, because of their parents and I want to take care of that,” Durbin said at Wednesday’s event at the Capitol.

According to the American Immigration Council, there are more than 200,000 such documented dreamers who could face deportation after they turn 21. Numbers for Arizona were not immediately available Wednesday.

But Robert Law, the director of regulatory affairs and policy at the Center for Immigration Studies, said the bill may not be necessary for people in Siddiqui’s situation. They have alternate ways to stay in the country, he said, such as getting a school or work visa.

He also said the law would be unfair to others who do not have an H-1B visa and have to go home once their green card expires.

“Everybody else has to wait overseas, so it is a very special treatment,” Law said of the proposal.

He called the bill little more than an attempt by Congress to make up for failed immigration laws that force immigrants to be “perpetually in a waiting game” for permanent status.

But Rep. Deborah Ross, D-N.C., and a co-sponsor of the House version of the bill, said it’s past time for action. The House bill was introduced in July, and the Senate version in September, but neither has yet to get a hearing.

“Today I am proud to stand with this remarkable group that worked so hard to draw attention to the challenging circumstances and to advocate for a commonsense solution,” Ross said.

The bills have drawn bipartisan support, with eight Senate co-sponsors evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans, and 10 Republicans among the 38 sponsors on the House bill. Arizona Democrats, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema and Rep. Greg Stanton of Phoenix, are co-sponsors in their respective chambers.

Siddiqui, whose family brought him here from India when he was a year old, considers himself an American and urged passage of the bill that he said would “solidify how the government reflects whether we are American.” And said he intends to keep fighting for it.

“We keep on lobbying, going to senators and representatives. As constituents we have the power to push something through,” said Siddiqui, who plans to study pre-law at Vanderbilt University this fall.