Muscogee (Creek) Nation citizen Galen Cloud complained about traffic during the 10-hour drive from Okmulgee, Oklahoma, to his tribe’s homeland near Oxford, Alabama – before recalling how his ancestors had to walk that distance against their will.

“You think about it and you’re filled with madness, and then you just feel the pain and then you just hate to imagine what all they went through, just to get here,” Cloud said.

He was headed to Oxford, where city and tribal officials have worked to protect nearby lands of the Arbeka people, whose ceremonial town was located there pre-removal, according to RaeLynn A. Butler, Muscogee Nation’s Historic and Cultural Preservation Department manager.

The Arbeka site is just one of the projects – from Alabama to Michigan to Kansas – where tribes are increasingly buying back or being gifted back property in their ancestral homelands, either to build economic sustainability or to manage cultural preservation sites.

Cloud, a Muscogee National Council representative, said that if someone went looking for Muscogee people on the tribe’s ancestral homelands in Alabama or Georgia today, they wouldn’t find many “because we all are here in Oklahoma now.” The tribe and several of its ceremonial tribal towns were forced to move to Indian Territory, which became Oklahoma in 1907.

“It’s really important that we go back and let people know that we are still thriving. We are still here,” Cloud said. “There are still people who think that we still live in houses without running water.”

The same has been true in Kansas for the Kaw, or Kanza, people who gave the state its name, said James Pepper Henry, Kaw Nation vice chairman and director of the First Americans Museum.

Galen Cloud poses next to a tree on his Muscogee Nation homelands in Oxford, Alabama; At right is a photo of the Arbeka ceremonial grounds in Oxford. (Photos courtesy Galen Cloud)

“We’re virtually invisible there,” Pepper Henry said. “They see the name Kanza here and there, but they don’t make that connection that this is a real, living, breathing group of people that still exist.”

Pepper Henry was involved in the early negotiations that led to his tribe buying ancestral homelands near Council Grove, Kansas, in 2002. He said the small purchase of land two decades ago is a drop in the bucket for true recovery of Kaw Nation’s homelands.

“That land we purchased was the last vestige of our reservation lands in Kansas,” Pepper Henry said. “The Kaw Nation had 22 million acres in Kansas, and starting from around 1815, then through a subsequent series of treaties, our lands had shrunk to less than about 100,000 acres.”

Council Grove, now home to the Kaw’s Allegawaho Memorial Heritage Park, was the last place the Kaw people lived before they were forcibly removed in 1873 to what is now Kaw City, Oklahoma, on the Arkansas River.

“From 1850 to 1970, we went from 22 million acres to 10 acres of land,” Pepper Henry said. “That 10 acres was our cemetery in Oklahoma.”

Pepper Henry’s mission of raising awareness of the Kaw people will take another step forward soon when the Kaw’s Sacred Red Rock, called “Iⁿ ‘zhúje ‘waxóbe,” is soon returned to its rightful location, thanks to a $5 million grant from the Mellon Foundation. The rock was moved to Lawrence, Kansas, in 1929 as part of the town’s 75th anniversary celebration.

The Shawnee are another Oklahoma tribe reclaiming homelands in Kansas. According to a news release from the tribe, the Kansas State Historical Society has returned the 0.52-acre Shawnee Indian Cemetery to the Shawnee people.

Osage Nation Principal Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear said his tribe is making progress toward economic growth in its ancestral homelands, having purchased 28 acres in Osage Beach, Missouri, for a hotel and casino resort. Osage Beach is the site of what was the largest Osage village before removal in 1808, the first of several relocations that would land the tribe in present-day Pawhuska, Oklahoma.

Osage Casino CEO Byron Bighorse said the project – with a casino, hotel, sports bar, restaurant and meeting space, among its amenities – will bring an estimated $60 million investment to the Lake of the Ozarks region, including new jobs, tourism and revenue.

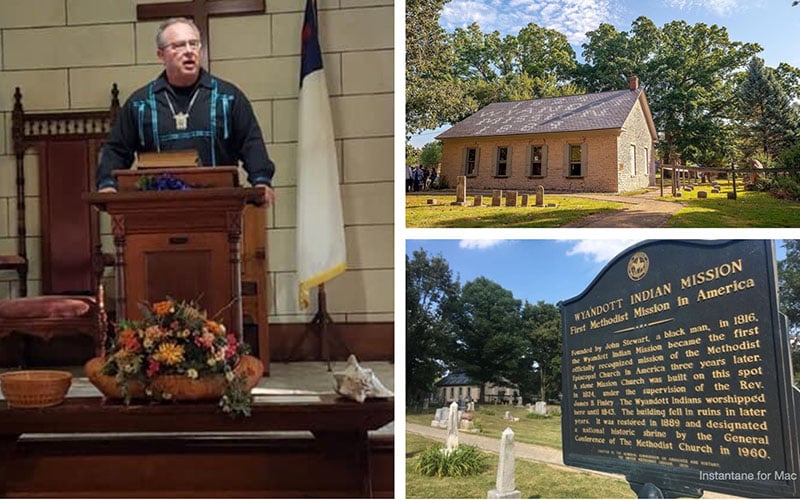

Wyandotte Chief Billy Friend preaches at the Wyandotte Indian Mission Methodist Church. At right are the reclaimed Ohio church and the Wyandotte Indian Mission Methodist Church historical marker. (Photos courtesy by Billy Friend)

Standing Bear said in his eight years as principal chief, the tribe has bought back about 55,000 acres in Oklahoma, as well as reclaiming another 160 acres of ancestral homelands in Kansas. The Osage had lost 90% of their Oklahoma land after removal, from nearly 1.5 million acres to under 150,000, he said.

“When I ran for office, I said this administration would be built on three pillars: land, our language and our cultural history,” Standing Bear said.

Wyandotte Nation Chief Billy Friend said his people have not been able to visit a church on ancestral homelands due to the pandemic and travel restrictions, making the land reclamation the tribe has been able to accomplish all the more important.

The church where Wyandotte ancestors once learned to read, write and worship was given back to the tribe from Methodists in Upper Sandusky, Ohio. The tribe in 2015 purchased 16 acres of ancestral homelands in what is now Brownstown, Michigan, and in 2018 began efforts to reclaim the church in Ohio, which came to fruition in 2019, Friend said.

He said the Wyandotte people will visit the church in July for the first time since the pandemic began. Not visiting these past two years, he said, has been difficult.

“I think it’s had a really big impact on many of us and especially those that are getting older, to not be able to go back and relive that experience or have that experience for the first time,” Friend said.

For Cloud, who previously served as historic preservation officer for Thlopthlocco Tribal Town, it’s important to preserve those histories.

“When we were forcibly removed from there, the Arbeka people just had whatever they could carry,” Cloud said. “The main thing they brought was the fire that still burns today.”

– Gaylord News is a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication, which has partnered with Cronkite News to expand coverage of Indigenous communities.