WASHINGTON – Oklahoma’s Five Tribes are pushing back against critics of tribal sovereignty, as the Supreme Court prepares to hear a case Wednesday that could solidify the impact of its 2020 ruling that recognized reservations over nearly half of Oklahoma.

The 2020 McGirt v. Oklahoma ruling determined that 3 million acres in eastern Oklahoma were still part of a Muscogee reservation established in the 19th century. The decision stripped the state of its ability to prosecute major crimes committed by members of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation on tribal lands, saying those crimes had to be prosecuted in federal or tribal courts.

Since that ruling, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals determined that eastern reservations of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Quapaw and Seminole nations were also never disestablished, giving the tribes authority over their lands’ criminal justice rather than the state.

The ruling has been repeatedly attacked by Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, who charges that it has “hamstrung law enforcement in the state.” And it recently became an issue in the state’s June 28 Republican primary, when a candidate in the race to replace outgoing Rep. Markwayne Mullin, R-Okla., said his priority in Congress would be to overturn McGirt.

The candidate, John Bennett, who is also the state’s Republican Party chairman, was also quoted in the Washington Examiner this month suggesting that Congress should “disestablish the Muscogee Nation reservation.”

The Inter-Tribal Council of the Five Civilized Tribes – Muscogee, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole – quickly pushed back at Bennett’s stance.

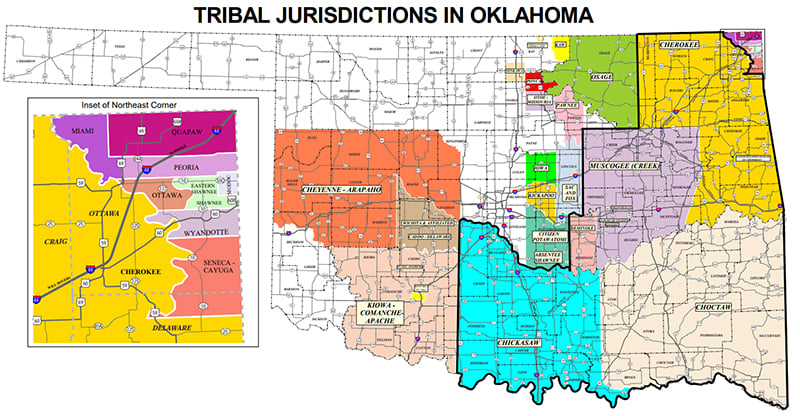

This map shows the many tribal lands in Oklahoma. (Photo courtesy of Oklahoma Department of Transportation)

“Oklahoma is strongest when our tribes are at the table,” the Five Tribes leaders said in a statement after Bennett’s remarks. “Candidates who seek to restrict our rights and disestablish our reservations, after the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed twice that they have always existed, do not deserve to represent our state.”

It’s just the latest fight over the decision that tribes have hailed as a “historic” recognition of their sovereignty, and Stitt had criticized as “destructive.”

Since McGirt was handed down, the state has filed more than 30 petitions with the Supreme Court challenging the ruling, and the justices this year agreed to consider one, Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta. That case asks whether the state can prosecute non-Indians charged with committing crimes against tribal members on tribal lands.

Stitt applauded the court’s decision to take the case.

“Criminals have used this decision to commit crimes without punishment. Victims of crime, especially Native victims, have suffered by being forced to relive their worst nightmare in a second trial or having justice elude them completely,” Stitt said in a statement at the time. “I will not stop fighting to ensure we have one set of rules to guarantee justice and equal protection under the law for all citizens.”

Stitt has routinely criticized the ruling on multiple platforms, including a pinned tweet on Twitter that says McGirt has “ripped Oklahoma apart” and features a clip from his March 30 appearance on Fox News to discuss the ruling.

The state’s brief to the Supreme Court argues that, unless the federal government has specifically pre-empted it, Oklahoma has the authority to prosecute in cases such as Castro-Huerta.

Oklahoma tribes have expressed consternation at the state’s approach, and the Five Tribes joined to file a brief this month supporting McGirt. The brief detailed the tribes’ frustration with what it called the state’s “attack” on tribal interests, but reemphasized the nations’ willingness to cooperate in implementing McGirt fully.

“The State badly misses the mark when it argues that the Nations lack a significant interest in the outcome of this case,” the tribes’ brief says. “Despite the State’s steadfast resistance, the Nations and United States are effectuating that allocation through increased resources and intergovernmental collaboration in which the Nations are crucial links.”

The case being heard Wednesday involves Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta, who was convicted by a Tulsa district court in 2015 of neglecting his stepdaughter, who is a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Castro-Huerta is not.

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals cited McGirt as it vacated Castro-Huerta’s conviction and 35-year sentence, because the crime involved a Native American and occurred in Indian Country.

The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case, but only on the question of whether the state “has authority to prosecute non-Indians who commit crimes against Indians in Indian Country.” It will not reconsider McGirt, which the state had asked for.

On Friday, the Muscogee Nation made clear that it was ready to fight any effort to curtail its sovereignty.

“The Muscogee (Creek) Nation will continue to fight in every venue – from the courts to Congress – to preserve its sovereignty and pursue justice for victims of crimes,” the nation said in a statement.

– Gaylord News is a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication, which has partnered with Cronkite News to expand coverage of Indigenous communities.