WASHINGTON – It took less than a day for opponents to file multiple court challenges to a new Arizona law requiring proof of citizenship to vote, a measure almost identical to one rejected by the Supreme Court in 2013.

The sponsor of HB 2492 insisted the measure is on “sound legal footing,” and all but dared opponents to test it in court. They did just that, with no fewer than five groups filing lawsuits Thursday in U.S. District Court, charging the law imposes “arbitrary and discriminatory burdens on eligible Arizona voters.”

“It’s going to disenfranchise thousands and thousands of voters,” said Araceli Villezcas, a spokesperson for One Arizona, an advocacy group that was not party to any of the lawsuits. “This is not election integrity.”

But the sponsor of HB 2492 insisted that the measure, signed into law Wednesday by Gov. Doug Ducey, is “a giant step toward ensuring elections are easy, convenient, and secure in our state.”

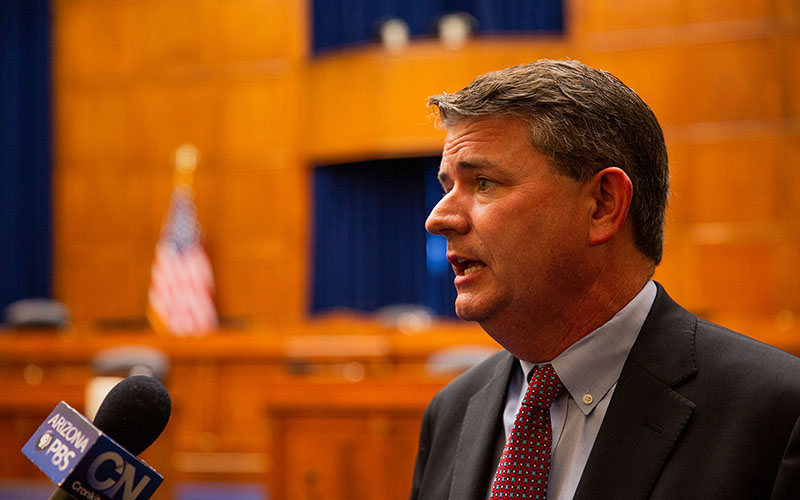

“HB 2492 is an incredibly well-crafted piece of legislation that is on sound legal footing and broadly supported by voters of all political parties,” said Rep. Jake Hoffman, R-Queen Creek, in a prepared statement. “I am confident that should Democrats challenge HB 2492 in court it will only serve to further reinforce its clear constitutionality.”

The law would require would-be voters to provide documents proving their citizenship before they would be allowed to vote in state or federal elections. It would also require that county recorders reject state voter registration for applicants who cannot provide such documents and makes violation of the law a class 6 felony.

The law mimics Proposition 200, a 2004 initiative approved by voters that required proof of citizenship to register. But that law was rejected in 2013 by the Supreme Court, which said states are required to accept a federal voter registration form under the National Voter Registration Act that only requires voters to check a box attesting to the fact that they are citizens.

Critics said the new law repeats the mistakes of the old one.

“Arizona has tried to impose proof of citizenship requirements like this on voters in the past,” said Will Wilder, a fellow with the Brennan Center for Justice. “The Supreme Court very clearly told them nine years ago that that was not OK.”

That was echoed by E.J. Dionne, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, who said the new law “on its face … may run afoul of a Supreme Court decision back in 2013 on state efforts to impose various citizenship requirements.” But Dionne, the author of “100% Democracy: The Case for Universal Voting,” also noted that the court is significantly more conservative now than the one that ruled in the previous case.

“You’ve gone from a much more narrowly divided court to a court with a 6-3 conservative majority,” he said. “I would guess that the sponsors think just maybe this new iteration of something they’ve been trying to do for a while will get to a differently constituted Supreme Court, and maybe they’ll get a different result than the one they got before.”

That case, Arizona v. Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, was cited in lawsuits filed Thursday on behalf of Mi Familia Vota, and a second suit filed on behalf of Living United for Change in Arizona, the League of United Latin American Citizens, the Arizona Students’ Association and ADRC Action.

“HB 2492 was adopted in explicit defiance of federal law and the United States Constitution,” said the second suit, filed by the Campaign Legal Center. “After nonpartisan legal staff advised the Arizona Legislature that the law likely violates federal law, one of the bill’s proponents expressly acknowledged that defiance is a purpose of HB 2492.”

The Supreme Court’s 2013 ruling led to a system in Arizona in which voters who used the state registration form could vote in all elections in the state, while those who used the federal form could only vote in federal elections. Opponents said the “bifurcated” election system was already confusing enough, and the new law would only make it worse.

Dionne said the law puts state and county governments, “in an impossible situation where either they abide by a Supreme Court decision and don’t enforce the law, but if they do that they are in violation of a new state law.”

“You talk about being between a rock and a hard place,” he said.

Secretary of State Katie Hobbs had urged Ducey to veto the bill that she said would “lead to voter confusion” and “creates new barriers for voters that are disconnected from any legitimate election integrity purpose.”

But Ducey said in his transmittal letter to Hobbs that the bill is needed to address the growing number of voters who have not had to prove their citizenship, which he said has grown from 21 in 2014, when the federal form was first used in Arizona, to 13,042 today in Maricopa County alone.

HB 2492 is hardly the only election legislation Arizona lawmakers considered this year: The National Conference of State Legislatures said there were 147 election-related bills filed in the state this year, a little more than 8% of the 1,793 filed nationwide. Election bills have grown steadily in the state, from about 51 a year between 2012 and 2020, to 122 bills last year.

“I think Arizona certainly stands out as one of the most aggressive in trying to pass new laws, curbing access compared to 2020,” Dionne said. “But it is clearly not alone.”

And Wilder said the “overly burdensome” law is less about protecting election integrity than it is part of an ongoing effort to “push new kinds of restrictions on voting” after “completely debunked” claims of fraud in the 2020 election.

“It’s disappointing to see that they’ve used this to pass a bill that is, you know, completely unnecessary, and also something that they’ve very clearly been told was illegal in the past,” Wilder said.