WASHINGTON – Leaders of two Arizona tribes asked lawmakers Wednesday to support funding for development of critical water infrastructure and to OK a bill that would let tribal water be sold to others in the drought-stricken state.

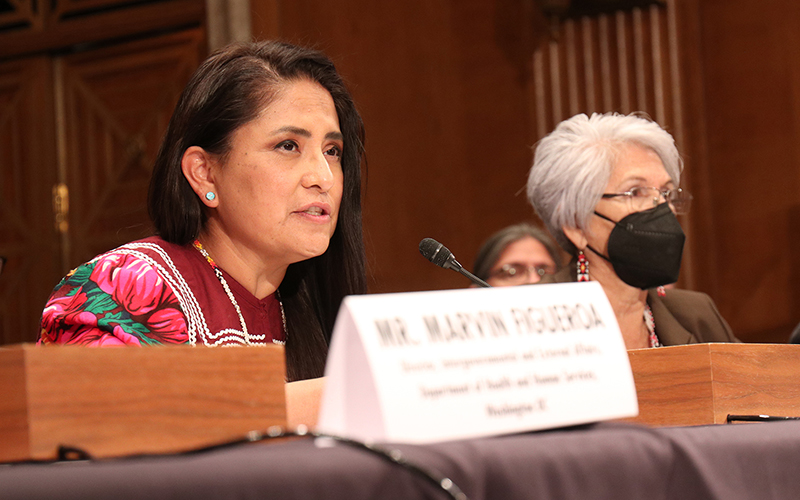

White Mountain Apache Chairwoman Gwendena Lee-Gatewood told the Senate Indian Affairs Committee that her tribe needs more time and money to complete a long-delayed rural water system promised by the federal government more than 10 years ago.

And Colorado River Indian Tribes Chairwoman Amelia Flores said her tribe has deals to reallocate some of its water, but needs congressional approval to do so. But Flores said the hearing was about more than just water rights and infrastructure.

“This bill will allow our tribes sovereignty, it’ll enhance and strengthen our sovereignty for our tribal people,” Flores said after the hearing.

Both Flores and Lee-Gatewood appealed for urgency, citing the megadrought that is gripping Western states.

“This is a critical time in the Colorado River Basin. We are facing a mega-drought and Arizona is Ground Zero,” Flores said in her testimony.

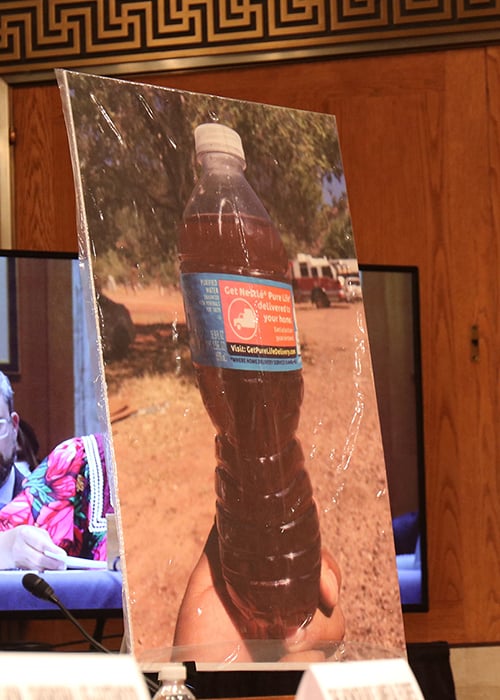

White Mountain Apache Chairwoman Gwendena Lee-Gatewood showed lawmakers a picture of the tainted water collected near Carrizo on her tribe’s reservation. (Photo by Reagan Priest/Cronkite News)

Sen. Mark Kelly, D-Ariz., who sponsored both bills with fellow Arizona Democratic Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, echoed the need for action both for tribes and for the state in general, as it faces historic water shortages.

“The issue is a priority for me because Arizona is on the frontlines of this megadrought, and in many instances, tribal nations are among the most vulnerable to its effects,” Kelly told the committee. “At the same time, tribes hold significant water rights that can position them to lead on water conservation.”

The White Mountain Apache bill would give the tribe an additional two years, from 2023 to 2025, to break ground on a rural water system to replace failing wells on the reservation. The project calls for a dam across the North Fork of the White River and a water treatment and distribution system that will supply water directly to tribal members.

The project was first promised by the federal government in 2010 to settle water claims by the tribe, but has been delayed by environmental review and engineering problems. Kelly’s bill would also add another $250 million for the project to account for the delays and cost overruns.

“The tribe’s current water sources and infrastructure have continued to be grossly inadequate to meet the current demands and needs of our reservation communities,” Lee-Gatewood said in her testimony. “We are in urgent need of a long-term solution for our drinking water needs.”

Lee-Gatewood said that with continued federal support, the plant could provide drinking water to the community as soon as 2028.

The second bill would let the Colorado River Indian Tribes lease some of their Colorado River water allotment to other Arizona communities, and to reinvest the revenue into improving water infrastructure on tribal land.

Flores said the tribes have taken steps to reduce the amount of water they take from the river, and leaving more than 200,000 acre feet in Lake Mead since 2016. She said the tribes want to do more, including diverting some of their water to preserve habitat elsewhere on the river, but they cannot do so without congressional approval.

“Right now we cannot make water available for off-reservation river habitat that is suffering as water levels drop,” Flores said. “This bill will help us support the native plant and endangered fish restoration programs along other stretches of the river like we do on our reservation.”

Colorado River Indian Tribes Chairwoman Amelia Flores, left, told the Senate Indian Affairs Committee that her tribe has helped save water in the river and wants to do more, but needs congressional approval to do so. (Photo by Reagan Priest/Cronkite News)

With the revenue earned from leasing the water to other areas in Arizona, she said, the tribes will be able to invest in water-efficiency programs to help conserve water used from the Colorado River.

Lee-Gatewood also explained how the proposed rural water system would enhance tribal sovereignty for the White Mountain Apache by letting them control their own water on tribal land.

“I cannot overstate the importance of our water rights settlements and the White Mountain Apache Tribe’s rural water system in the health and welfare of our people,” she said.

“If this issue is not resolved, the completion of the rural water system project will be threatened, thereby increasing the ultimate cost to the tribe and to the United States and delaying delivery of life-sustaining drinking water to our reservation communities,” Lee-Gateweood said.

Flores said after the hearing that she is optimistic about the passage of both bills, even if they won’t come as quickly as the tribes would like.

“It’s just the beginning,” Flores said. “We’re at the doorstep, we just haven’t gone through the door yet.”