LOVELAND, Colo. – On its way to your kitchen faucet, precipitation that falls in the Colorado River Basin takes a long and winding journey. High mountain snowmelt trickles through streams, rushes through rivers and flows along a chain of man-made tunnels, canals and reservoirs before it ever reaches city pipes.

For tens of thousands of people on Colorado’s Front Range, that journey soon will involve another turn, as the Chimney Hollow Reservoir takes shape in the hills above Loveland. Proponents of the build call it an investment in the future of a growing Colorado, while critics say impounding 90,000 acre feet of water will further strain an already taxed watershed.

The build itself is a feat of engineering, and a striking example of mankinds’ ability to reshape the natural world.

Since work began in August, the Chimney Hollow site has teemed with activity. Building a reservoir involves far more than just gouging a hole in the ground. This project requires the construction of a massive dam – the tallest built in the United States in 25 years.

“Seeing it on plans and seeing pictures of it doesn’t really do it justice until you’re here standing at the bottom, looking up 350 feet to the top of the dam, a hundred feet below where original ground was,” said Jeremy Deuto, project engineer for Chimney Hollow.

To build something at this scale, machines are moving a volume of earth that’s hard to wrap your head around.

“We’re filling 100-ton trucks,” said Joe Donnelly, Chimney Hollow’s project manager. “We need a whole load of rock placed on the dam every two minutes, five days a week, for two and a half years.”

In a state where “feeling small” often is prompted by towering mountains and a vast expanse of blue sky, it’s an odd sensation to be dwarfed by something not natural. In this case, an excavator. Shoveling heaps of dirt into a waiting dump truck with tires twice the height of a person, this excavator could dig the foundation of a house with just three scoops.

The sprawling Chimney Hollow Reservoir will fill much of this valley, wrapping beyond the field of view shown here. Critics say new infrastructure like this will add strain to an already taxed watershed. (Photo by Alex Hager/KUNC)

Each gargantuan yellow vehicle contributes to the ordered chaos – a maelstrom of whirs and croaks and beeps as the ground is reshaped according to a carefully planned blueprint. It’s hard to see the bigger picture from the bottom of the soon-to-be reservoir, but a perch from high above provides a sweeping view of the gestalt.

Up here, with the noisy work below reduced to a gentle din, Jeff Stahla describes how the reservoir will wrap around the cliffs we’re standing on and extend beyond our field of view.

“When you build a dam of this size, you’re not thinking of something that’s going to happen just in a few months or a year to address your needs just a few years down the road. You’re thinking generationally,” said Stahla, a spokesman for Northern Water Conservation District, which is overseeing construction of the project.

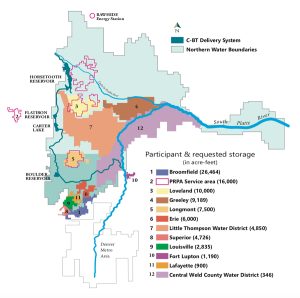

That generational thinking helps explain why the project is such an undertaking. When it’s finished, planners say the reservoir will provide 30,000 acre-feet of water each year to thousands of people in such towns as Broomfield, Loveland, Greeley and Longmont.

It took about two decades to get the project permitted, and it’ll be four more years of construction and then three more years of filling before the reservoir is completed. The total cost of building the reservoir comes to about $500 million – roughly $340,000 for each day of construction. Related work will bump the cost of the total project to $650 million.

Stahla said additional water storage will help water providers gain some certainty and more smoothly supply homes across the fluctuation of wet years and dry years – a practice that has been baked into water projects for centuries.

“We’re just like humans all over the planet looking to time water release in addition to storing it,” he said. “So this piggybacks off of what we have, as a species, been doing all over the world. It’s just interesting that a lot of us don’t get to see it on this scale in the course of our lifetimes.”

“Seeing it on plans and seeing pictures of it doesn’t really do it justice,” says project engineer Jeremy Deuto, right, with project manager Joe Donnelly. The Chimney Hollow Reservoir was proposed nearly two decades ago. (Photo by Alex Hager/KUNC)

‘No water to fill those buckets’

Although dirt now is being moved at Chimney Hollow, the path was lined with opposition. Farther upstream, critics of the project characterize it as another piece of overdevelopment on the Front Range and an additional burden on a dwindling water supply that shouldn’t be stretched any thinner.

“You can have a bunch of buckets, and you can build more buckets to put water on the Front Range,” said Jen Pelz, wild rivers program director for the conservation group WildEarth Guardians. “But the reality is, if the projected climate change impacts come to fruition – which all indications are, they’re coming to fruition quicker than we even thought – there’s going to be no water to fill those buckets.”

The Colorado River Basin is under a level of strain it hasn’t experienced in more than a millennium, with drought driving supply down and population growth driving demand up. Scientists have outlined a grim future for the region, predicting that human-caused climate change will shrink the West’s water supply.

Colorado is built on a system of moving water around. About 80% of Colorado’s water falls on the Western Slope of the Rocky Mountains, but about 80% of the state’s 5.8 million people live east of the Rockies. For a century and a half, those people have relied on a complex system of canals and tunnels that shuttle water across and through the mountains – often to reservoirs that store it for timed release.

Although that system is crucial to Colorado’s existence as we know it, Pelz opposes the development of most new projects because climate change has put their functionality into question.

“I think that spending a bunch of money on a reservoir when you don’t have the water to fill it is kind of silly,” she said, comparing it to the quote “‘A refrigerator that’s empty doesn’t do a lot of good to solve someone’s hunger crisis.’”

Opposition to Chimney Hollow also came from those near the lakes and rivers that someday will be rerouted to fill it. In Grand County, opponents argue that reducing water levels of nearby rivers and lakes could cause algae blooms and jeopardize recreation business in the mountains.

This map shows the location of Chimney Hollow Reservoir and the communities it will serve. An acre-foot of water is the amount needed to fill 1 acre of land to a height of 1 foot. One acre-foot generally provides enough water for one or two households for a year. (Map courtesy of Northern Water Conservation District)

“When is enough enough?” asked Ken Fucik, vice president of the Upper Colorado River Watershed Group. “When are we going to say every drop of water that is up here will go down to the Front Range? You can’t continue to add population without providing them water, we all recognize that. But where’s that water going to come from? There’s only so much. We are a finite resource.”

Fucik, a retired environmental consultant, also contends that the region’s shrinking water supply has made new projects ill-advised.

“We don’t live back in the ’20s when there were small populations and there was plenty of water,” he said. “Our biggest question to the people that make these decisions is, ‘Do you even know how much water is available?’”

Back on the more populated side of the mountains, the reservoir’s developers say it’ll be a pivotal tool in sustaining communities and lifestyles as they’re known today.

“If we’re going to be able to exist and offer the same opportunities to our children and grandchildren on the Front Range,” said Stahla of Northern Water, “We should consider – and we’re doing it here – capturing the water when it’s available so that we have flexibility in those years when we don’t have it.”

This story is part of ongoing coverage of water in the West, produced by KUNC in Colorado and supported by the Walton Family Foundation. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial coverage.

The Chimney Hollow Reservoir will require the removal of about 2 million cubic yards of earth. The 90,000 acre-foot reservoir will take four years to complete, then three more years to fill with water. It’s designed to help store water for homes in rapidly growing cities along Colorado’s Front Range. (Photo by Alex Hager/KUNC)