Oklahoma is in a power struggle with its 39 tribes over criminal jurisdiction and whether Native American reservations in the state still exist, but legal experts say Arizona and other Western states settled most of those issues years ago.

In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Muscogee Reservation in Oklahoma had never been dissolved by Congress, meaning the federal government – not the state – had jurisdiction over crimes committed on Muscogee lands.

The case involved Jimcy McGirt, an enrolled Muscogee tribal member who Oklahoma prosecutors convicted of sex crimes. The Major Crimes Act, first enacted in 1885, gives the federal government jurisdiction over crimes on tribal lands.

The foundation for the McGirt decision is a case decided by the New Mexico Supreme Court in 2006, said Jerri Mares, legislative affairs director for the New Mexico attorney general. It ruled that the state did not have jurisdiction to prosecute crimes on New Mexico reservations.

“While New Mexico will undoubtedly feel an impact of the McGirt v. Oklahoma decision in the future,” Mares said, “New Mexico case law has already established a framework for who can exercise jurisdiction over crimes committed by members of Indian tribes in Indian Country.”

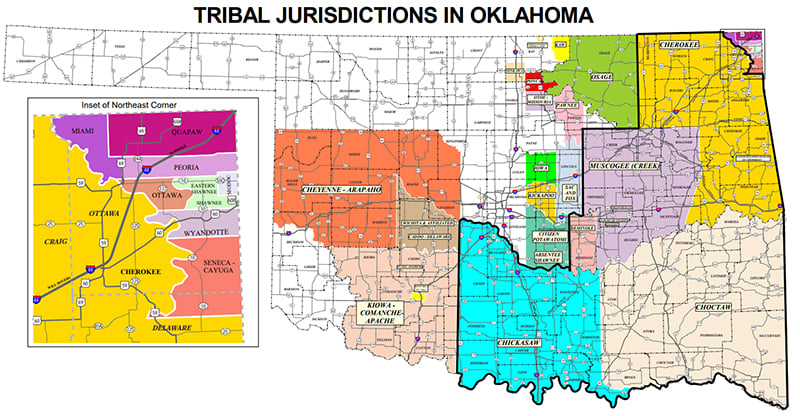

Since McGirt was handed down, Oklahoma courts have ruled that the reservations of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole and Quapaw tribes were never lawfully dissolved.

Stephen Greetham, senior legal counsel for the Chickasaw Nation, is critical of Oklahoma’s position on tribal jurisdiction under McGirt v. Oklahoma. (Photo courtesy of Chickasaw Nation)

Robert J. Miller, a professor at ASU’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and a member of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe in Oklahoma, said his tribe’s 14,000-acre reservation potentially could be re-recognized under McGirt.

Before McGirt, Miller said, Arizona had by far the most tribal land within its boundaries, with 27%. Now, with six reservations re-established, Oklahoma leads with 43%.

“There’s no state making the same arguments Oklahoma is,” Miller said. “Oklahoma’s acting like this is the end of the world. Yes, 43% is a pretty big deal and it’s a shock to the system. I called this case a bombshell and it was a bombshell for the feds, the state and the tribes.”

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt has been in conflict with tribes beginning with casino gaming compacts in 2019, a year before the McGirt ruling. In 2021, the Republican went toe-to-toe with tribal leaders over hunting and fishing compact costs and the expiration of gaming compacts.

Stephen Greetham, Chickasaw Nation’s senior counsel, said “there’s no ambiguity left to be reasonably argued” in the application of the law.

Greetham said that in his experience working with his team, the governor only wants to work under a framework of rolling back McGirt, “and the tribes aren’t going to do that.”

“Each one of those states (outside Oklahoma) has been dealing with this for quite a long time,” Greetham said. “They have invested, built and structured their law enforcement systems in order to deal with the law as it is. What Oklahoma is doing, instead of working with the tribes and working with the law as it is, it’s continuing arguments to try to say ‘No, not us, we’re different.’

“It doesn’t work that way.”

Rachel Roberts, communication director for the Oklahoma Attorney General Office, indicated there might be room for dialogue with tribal nations.

This map shows the many tribal lands in Oklahoma. (Photo courtesy of Oklahoma Department of Transportation)

“The attorney general has had constructive conversations with tribal leaders and looks forward to more in the future,” she said this month.

Oklahoma’s position isn’t unique, according to Monte Mills, a professor of federal Indian law at the University of Montana. State and local concerns over tribal rights and their impact on nontribal citizens often are at the core of such conflicts, he said.

“That’s not to say there haven’t been conflicts over whether the state exerts authority or taxes certain people within reservation boundaries,” Mills said. “Those have continued, but that basic question about whether the reservations exist hasn’t been an issue here recently like it has in Oklahoma.”

Alexander Skibine, professor at the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law, pointed to continued disputes about reservation boundaries for the Ute Tribe.

“Although McGirt is only relevant to Oklahoma in the immediate future, disputes about reservations’ boundaries or disestablishment have affected a number of states,” Skibine said. “Here in Utah, the state has had a long history in refusing to cooperate fully with federal rulings concerning reservation boundaries.”

Miller said Arizona in the past has litigated a number of Supreme Court cases against the tribes. In 1959 and 1973, the state sued individual tribal members in state court as well as a case in which the state tried to tax the salary of a Native woman who lived on the Navajo Nation. Arizona, he said, has learned to recognize tribes for what they are: an equal body of government.

“The state recognizes tribal governments as constitutionally recognized governments, and you have to deal with them the same as you deal with other states or you deal with a city or a county,” Miller said. “There’s a lot of obligations on the tribes in Oklahoma now that they didn’t have before. Most of them are working very diligently to absorb these new powers. They’re cooperating with the feds, they want to cooperate with the state. Will the state?”

Nancy Marie Spears is an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. Gaylord News is a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication. For more stories, visit GaylordNews.net.