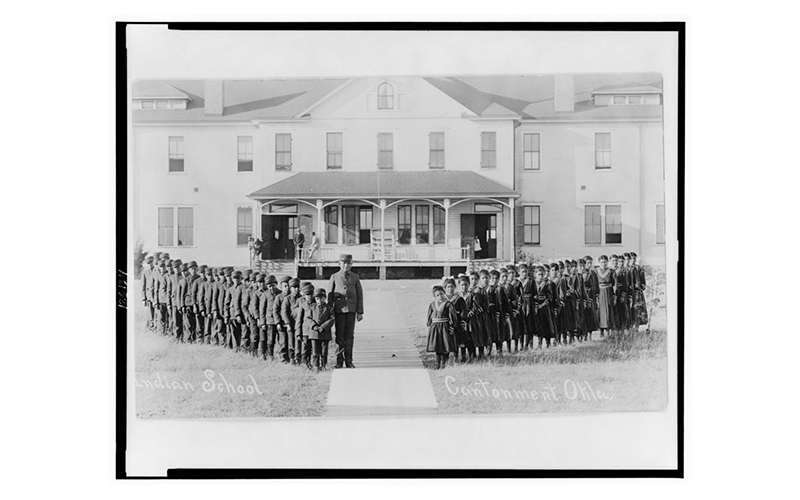

The Supreme Court has agreed to consider to the Indian Child Welfare Act, which gives Native American families preference for foster or adoptive placement of Indigenous children. Opponents say it is an illegally race-based law, but supporters call it best for Native children, keeping them close to their family and cultures. (Photo by Emily Sacia/Cronkite News)

WASHINGTON – The Supreme Court agreed Monday to hear a challenge to the Indian Child Welfare Act filed by a white Texas couple that was almost denied the chance to adopt a Native American boy who was set to be placed with a Navajo family.

Jennifer and Chad Brackeen argue that the act, which requires child welfare agencies to give preference to Indigenous families when placing Indigenous children, unconstitutionally discriminates on the basis of race and is not always in the best interest of the child.

But supporters – including 26 states that filed petitions to uphold the law – commonly call the ICWA the “gold standard” of child welfare policy, that allows Native children to stay as close to their families and culture as possible when they have to be removed from their parents’ custody.

“It’s helped countless numbers of Native children be able to stay in connection with their families and with their culture and have the ability as they grow older to have those relationships that they otherwise might not have,” said David Simmons, director of government affairs and advocacy for the National Indian Child Welfare Association.

The Brackeens are among seven individuals and three states – Texas, Indiana and Louisiana – that sued to change the 1978 law that they claim is not only discriminatory but exceeds Congress’ authority and unlawfully requires states to enforce it.

“This is something that hurts Native American children and Native American parents and takes their rights away,” said Timothy Sandefur, the vice president for litigation at the Goldwater Institute, which has filed a brief in support of the opponents.

“Tribal governments like ICWA because it gives tribal governments a lot of power, but it takes that freedom away from the kids themselves and from their parents,” Sandefur said.

In Arizona, Native American children accounted for 1,113 of the 13,581 children in the foster care system in fiscal 2021, or 8.2%, according to data from the Arizona Department of Child Safety. Nationally, Native children made up 2% of children in the foster care system in fiscal 2020, according to the Children’s Bureau in the Department of Health and Human Services.

The Brackeen case began when the Texas couple tried to adopt A.L.M., a child who was removed from his Navajo mother and Cherokee father when he was 10 months old and placed in foster care with the Brackeens. But when the Brackeens filed to adopt the boy, the Navajo Nation stepped in, saying it had found a Navajo family in New Mexico.

A family court ordered the boy placed with the Navajo family. But when the Brackeens appealed, the Navajo family withdrew, saying it “could not face the uncertainty of whether they would get custody,” according to the Navajo Nation’s court filing.

The Brackeens were eventually able to adopt the boy, but not before filing suit in federal court challenging the ICWA. They claimed in their October 2017 suit that the law is unconstitutional because its placement preferences “impermissibly discriminate on the basis of race, exceed Congress’s power over Indian affairs, and impermissibly commandeer state judges.”

A district court ruled for the Brackeens. But a sharply divided 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals later upheld the law, while ruling that some questions about whether it “commandeered” state officials are unconstitutional.

Both sides appealed. The Brackeens’ case is just one of four dealing with the ICWA that the Supreme Court combined Monday when it said it will consider the question of whether the law is discriminatory and whether it is congressional overreach into state affairs.

Besides the Navajo Nation, the suit has been joined by the Cherokee Nation, the Oneida Nation, the Quinault Indian Nation and the Morongo Band of Mission Indians. The Interior Department has also been joined by 26 states – which the 5th Circuit noted “are home to a large majority of federally recognized tribes” – and the District of Columbia in efforts to preserve the law.

Simmons disputed opponents’ claim that the law forces states to act, saying the cooperation between states, tribes and the federal government required by ICWA is actually a benefit.

“Child welfare is a service that needs more people,” Simmons said. “It needs more agreement, more collaboration. You can’t do that by cutting people out, you’re only going to make it worse. And that’s what ICWA does, it encourages those collaborations, public, private, and otherwise.”

Sandefur disagreed with the 5th Circuit’s ruling, saying ICWA “ treats people differently based on their biological eligibility for membership in a tribe,” which he argued crosses the line into a race-based law.

If the Supreme Court can find at least one provision of ICWA unconstitutional, it will open the law up for a comprehensive review by Congress, Sandefur said.

“It would require Congress to take steps to fix these constitutional problems … so it would require them to go back and amend the law in order to eliminate the race based restrictions and to fix these federalism problems,” he said.

Simmons said he believes these challenges to ICWA are not actually rooted in concerns for Native children or the constitutionality of the law, but are instead part of a larger push to deny power to tribal governments.

“We think that while they’re talking about ICWA, which is a very small issue here, what they’re really motivated by is a much bigger desire to diminish the ability of tribal nations to care for their kids, and also to care for their people in larger ways too,” he said.

The case is not likely to be heard until the court’s next term, which begins this fall.