PHOENIX – It was a hot summer night in Glendale when the neighborhood kids decided to play a football game. It started out friendly, but it didn’t take long for a fight to break out. To nobody’s surprise, Peter Chavez was dueling with a kid who was a lot bigger. Even though Chavez was the underdog, he didn’t back down. After they were separated, a local boxer who happened to be watching noticed Chavez’s “heavy hands” and told Chavez he should start boxing.

From that inauspicious beginning, Chavez has built a life anchored around the boxing ring and focused on kids who remind him of himself.

Even though Chavez had always preferred martial arts, he decided after the football fight to give boxing a try at the Phoenix Boys and Girls Club in Glendale. Chavez’s dedication was put to the test right away as he was required to train for a couple of hours every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Along with the demanding hours, the club also didn’t have a reliable ring, so the boxers trained on the basketball courts with whatever equipment they could find.

Those hardships paled in comparison to Arizona’s sauna-like summers.

“I remember it was horrible when I first started because there was no air conditioning or an open door,” Chavez said. “And when I started, it was summertime, 115 degrees, and I was dying.”

Despite the harsh conditions, Chavez continued boxing, even training on his off days. Chavez’s talented hands allowed him to develop into a good boxer quickly and he began competing in tournaments at local boxing gyms, where he was able to showcase his heavy hands and talent. His first 11 fights, he said, were all stoppages, or referee technical decisions, in which the referees called an end to the bouts.

“In amateur (boxing) you don’t get hardly any knockouts or stoppages because there are only three rounds,” Chavez said. “But I had really good power.”

During his amateur boxing career, Chavez’s trainer, Walt Hoskins, gave him the nickname “The Punisher.”

“I’m known for being really good at hurting my opponents with body shots,” Chavez said. “I would break them down, punish the body.”

Before the age of 24, Chavez racked up an amateur record of 37-3, including a Golden Gloves title that he won at 17.

At 24, Chavez decided to try and become a professional boxer. Unfortunately, his first three fights got canceled, stalling his progress. Also around this time, Chavez’s partner left him with their two toddlers, which made him reconsider his dream of becoming a professional boxer. The final straw for Chavez was when his health began to deteriorate.

“I passed out at work from exhaustion,” Chavez said. “I thought ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ You know, even though it was my dream. I can’t risk my safety because of my kids.”

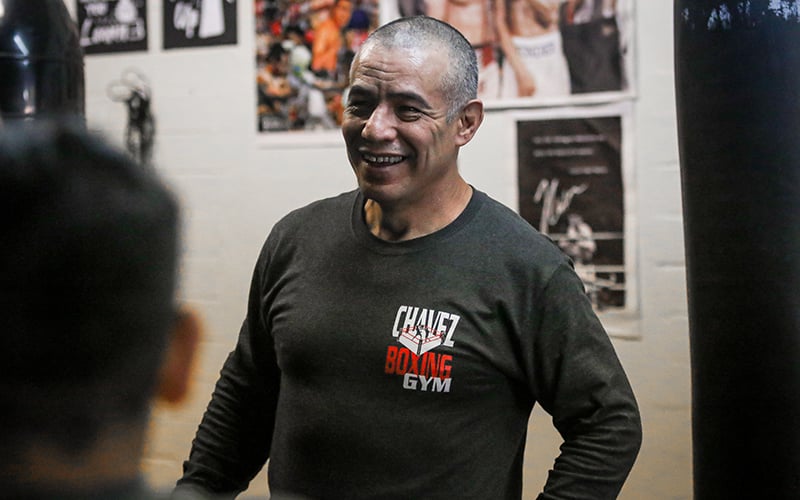

Chavez racked up a 37-3 amateur boxing record before the age of 24. (Photo by Harrison Zhang/Cronkite News)

Down, but not for the count

After giving up on his dream, Chavez began to build a nice life with his two kids and fiancée. It all unraveled when he got a DUI at 34. Chavez said his lawyer and other government officials told him they thought he would most likely be sentenced to around four months in jail, but instead he was handed a three-year sentence.

After serving two and a half years, Chavez was finally released, but there would be no getting his old life back. His fiancée left him shortly after he was released, forcing him to raise his children by himself. Chavez and his kids were homeless for a short time, living in furnished month-to-month apartments while Chavez tried to make enough money to support his family.

“He would ride his bike miles to his job, and would do what he needed to make ends meet,” Chavez’s son, Conrad, said. “I knew we didn’t have a ton of money but I always had what I needed. He did what he needed to do to provide.”

One day, Conrad saw an article in the Phoenix New Times promoting a “Tough Man Contest” that offered the winner a $2,500 prize. Chavez at first was hesitant to enter because he hadn’t boxed in 15 years, but he relented after his son begged him to reconsider.

“I basically did it for (my son),” Chavez said. “I didn’t want to let him down. He’s all proud of his dad and saying, ‘You can beat these guys.’ I’m like, OK, I’m going to have to train a lot and I have to do this and that.”

Chavez entered his first “Tough Man Competition” when he was 39. After winning the three elimination matches, he was crowned the winner and took home the $2,500 prize. Chavez continued to compete in the “Tough Man Competition” and won two more times, at 41 and 45.

Peter Chavez’s boxing gym is located on the intersection of N 16 Street and E Thomas Road. (Photo by Harrison Zhang/Cronkite News)

After his first victory, Chavez became a part-time boxing coach. He set up a studio in an office building where he shared the space with a dojo. As he built his clientele, he bounced around from space to space, even training boxers for a short time in a church on 34th Street and Van Buren. Located in a struggling area, the church was the perfect location for the neighborhood kids that Chavez was hoping to reach but less than optimal for his other clients.

“It was hard to (get) clients out there, like for one-on-one training,” Chavez said, “but it was good for kids and teens that wanted to box.”

Although Chavez needed paying customers to help him build his gym, he continued to train kids that he knew needed attention and the refuge that the ring provided – like he once did.

“I’ve seen so many people in my neighborhood and the bad ones get killed and go down the wrong paths,” Chavez said. “And then when I was doing boxing it was my escape, and it was something that I loved. So I knew there were a lot of other kids like that, too.”

Corner man for kids

Chavez’s son began bringing his friends from school to Chavez to train. Many of his friends wanted to learn “how to fight,” he said, but not a lot of them had the commitment to learn the complexities of boxing.

“The training was difficult and required a commitment,” said Chavez’s son, who added, “A lot of them didn’t last.”

One of Chavez’s clients at the time, a paralegal, introduced Chavez to the idea of starting a non-profit foundation to focus on training underprivileged kids. With help from the paralegal, Chavez was able to start the Chavez Boxing Foundation. The aim of the program, the website says, is to “uplift and support youngsters by helping them develop their confidence, build good character, be involved in their community, and learn self-defense.”

Chavez’s past helps him connect with today’s youth through his non-profit foundation that trains local underprivileged youth. (Photo by Harrison Zhang/Cronkite News)

Alfredo Valdivia, one of the foundation’s board members, trained with Chavez as a teenager. He said Chavez’s past helps him connect with the children.

“You know he really relates to a lot of the youth,” Valdivia said. “He’s been through so much, and him giving advice to me and a lot of the kids makes us realize that like there’s always a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Valdivia discovered Chavez’s program at 16 when he was looking for an activity that could help him stay in shape. Chavez instilled his passion for boxing in Valdivia, who still is an amateur boxer.

Luz Villa also discovered the Chavez Boxing Foundation when she needed it most and quickly realized that Chavez was more than just a coach.

“When you think of a father, you think of a man that’s going to love you no matter what,” Villa said. “A person that cares a lot about you. That’s what it feels like with Pete. It becomes natural to call him ‘Dad.’”

Chavez stepped in as a father figure in Villa’s life and showed her that she was appreciated. Chavez gave her granola bars and mac and cheese so she wouldn’t be hungry and was always there for her.

“I don’t know how I would have pushed through without him,” Villa said.

Whether it was taking her shopping for her high school prom dress or celebrating her birthday, Chavez always made sure she knew people cared for her.

“My favorite memory with Coach is when he would visit me on my birthday because he wanted to make sure it was celebrated,” Villa said. “I never had special birthdays and he knew that. So he made sure to make it the slightest bit special and it meant the world to me.”

Making kids feel comfortable and giving them confidence is what Chavez’s foundation is all about. Chavez has become a role model for many kids who are going through tough times and need structure to stay on the right path. For Chavez it’s more than just helping out the community. It’s helping out kids who are just like him when he was younger.

Chavez now owns a large boxing facility on North 16th St. called “Chavez Boxing Gym.” He offers one-on-one training for adults and children, while also teaching the youth from his foundation three days a week. Although Chavez’s job description is “boxing coach,” he knows that he is so much more to his clients.

“A lot of them have depression, anxiety, PTSD, and stuff,” Chavez said, referring to his clients. “So I’m like a counselor to them, too.”

From the outside, the Chavez Boxing Gym looks like a place where people train and stay in shape, but to the people on the inside, it is much more than that. To Luz Villa, it is a place where she can feel comfortable and appreciated. To Alfredo Valdivia, it is a school where he learns important lessons about perseverance and self-confidence.

And to Peter Chavez, the man who started it all, it is a temple where he can share his wisdom about boxing and life with members of his community.