Inspiring a new generation

Children like Cameron Dick, 11, who’s interested in black holes and theoretical physics. He lives in a city where science is in the backyard and events like the I Pluto Festival provide an outlet for new generations of Arizonans interested in science.

Aaron Dick, Cameron’s father, said he hopes his children take away an appreciation of “science and learning about research and how to do research.”

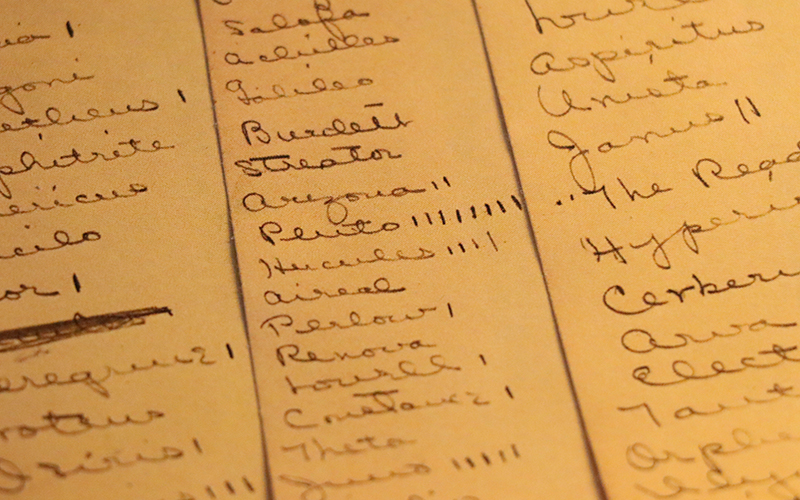

At Lowell, just a mile up the road from the theater, visitors follow a path of descriptive signs and busts, named the Pluto Walk, leading to the room where Clyde Tombaugh spent hours peering into the heavens.

Schindler said the discovery of Pluto – even though Pluto now is designated a dwarf planet – has shaped Flagstaff and northern Arizona.

“Flagstaff and even Arizona, you could say, is the home of Pluto, and I think there’s a lot of pride that goes with that,” he said. “If you’re from Flagstaff, you’re from the home of Pluto, and you know, it’s important both scientifically but also culturally, because the community does embrace that heritage.”

When Schindler speaks of Tombaugh’s discovery, it’s with admiration and awe that it still moves young people nearly a century later.

“He was 24 years old when he discovered this planet,” Schindler said, “and so when he was younger, he spent a lot of nights by himself on the farm, building his own telescopes. He just found it interesting, so I think it’s inspiring to think that anybody could achieve this.”