PHOENIX – Martine Garcia, a first-generation student at Chandler-Gilbert Community College, was surprised when he was asked a few years ago to be president of a new school club.

He hadn’t been particularly involved on campus, and the invitation to head the Male Empowerment Network, a support and mentoring group for minority male students, didn’t really make sense.

“My immediate reaction was, ‘Why is this person helping me? What do they want?’” Garcia recalled.

But he soon learned he’s part of a shrinking group when it comes to higher education: Men.

A generation of young men are disappearing from colleges – a trend accelerated by the pandemic. In Arizona, the trend is most visible at Maricopa Community Colleges. Arizona State University, however, has been able to buck the trend so far with a 5% increase in male enrollment in the 2020-21 school year.

The gender gap at colleges has been slowly growing for decades, according to the Department of Education. Women outnumber men when it comes to both enrolling and staying in college.

But this trend has reached unprecedented levels recently. The National Student Clearinghouse reported that women made up 59.5% of college students, while men made up 40.5% at the close of the 2020-21 academic year. This is a major shift in the collegiate population, which men historically have dominated. And it’s happening across all ethnic and socio-economic groups.

At the Maricopa Community Colleges, women make up roughly 59% of the student population, and men 40%. At the University of Arizona, male enrollment is down slightly, and at Northern Arizona University, about 8,000 more women are enrolled than men.

Although overall enrollment might be expected to drop in a national crisis, such as the pandemic, there’s little research as to why men are not pursuing higher education.

“It’s difficult to understand what’s happening with this generation of young men and why they’re opting out of that traditional path,” said Arizona state Rep. Lorenzo Sierra, D-West Phoenix.

One reason could be that young men are prioritizing the safety and happiness of their families in a time of uncertainty, she said.

“They’re being faced with the harsh reality that they’ve got to make money to help the family out. They’ve got to be working at this point,” Sierra said. “And then you throw upon that that going to college is expensive and that you’re going to end up in a hole before you even start your life.”

Students overall aren’t returning to college as might be expected after enrollment dropped during COVID-19, when many opted to take a break rather than take virtual classes. The National Student Clearinghouse reported that enrollment for all students continues to fall. The overall decline from 2019 to 2021 was 5.8%, but for men it was more than 10%.

Doug Shapiro, vice president and research and executive director of the clearinghouse, said at a news conference in October that if this continues, it will be the largest two-year enrollment decline in at least the past 50 years.

“There’s simply no upside from the recession, just a downside that we’re seeing,” he said. “These are the students who would normally be enrolling in droves during a recession, and then we (would) expect them to go back to work as the job market improves.”

Universities have always been conscious of under-enrollment for men of color, such as Garcia, and have created outreach programs to boost enrollment and graduation. But the downward trend is prominent among white males, whose enrollment declined 13.4% from 2019 to 2021, according to clearinghouse data. Enrollment by Black men dropped 14.8% and by Latino men 10.3%, the data says.

ASU, however, saw a record number of students enrolled in fall 2021, 14,350, and male students were majorities on the Tempe and the Polytechnic campuses.

“We’ve been very fortunate that we have not seen a lot of the enrollment trends … that a lot of the other schools, universities and community colleges are facing,” said Matt Lopez, ASU’s associate vice president of academic enterprise enrollment.

In fact, it reported a 5% increase in male students from 2020-21, despite COVID-19 and its fallouts.

“The university as a whole has one of the largest percentages of males at ASU that we’ve had in at least a decade, probably longer than that,” Lopez said.

Many factors make ASU a desirable option, he said. It’s convenient, with five campuses and nearly 300 online degree programs. Financial aid, scholarships and overall inclusivity may also make it more accessible than other colleges.

ASU is also known for excelling in retention, especially when it comes to freshman. The university says 86.2% of students return after their first year.

Although ASU touts retention, it did not report the rate of men who are graduating.

ASU’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, one of the largest engineering programs in the country, could be attracting male students, Lopez said.

In addition, he said, the STEM programs, which are historically male-dominated fields, have grown tremendously in recent years.

“I would not be surprised if our current freshman class … is one of the largest the Fulton schools have had,” he said.

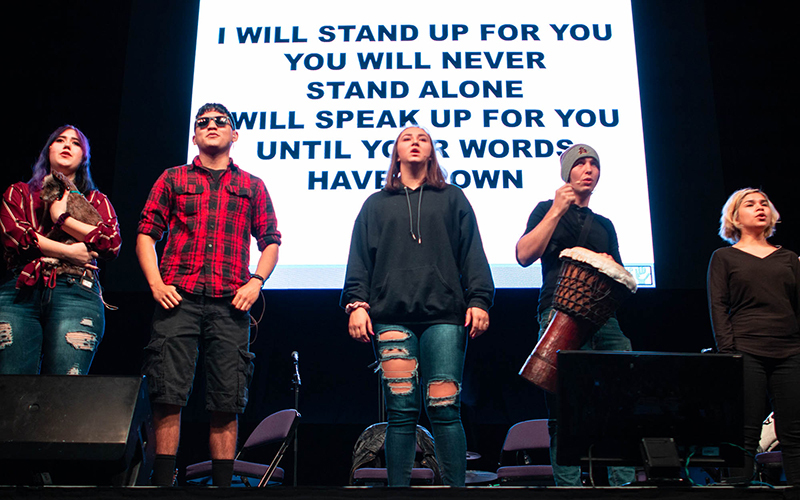

Despite ASU’s success, school officials still see the need to reach out to young men. ASU leads a program called Males in Higher Education, while the Maricopa Community Colleges have the Male Empowerment Network. Both focus on inspiring minority men to pursue higher education.

Martine Garcia attended Chandler-Gilbert Community College as a first-generation college student. (Courtesy of Martine Garcia)

Garcia, who’s now at ASU, said the network helped him navigate the college process. His parents, although always supportive of his journey, didn’t know how to help him because they hadn’t gone to college themselves.

He’s now the program director for TRIO Student Support Services at the Polytechnic campus. These opportunity programs are designed to support first-generation, low-income, students with disabilities and veterans seeking a college degree.

But men aren’t signing up for Garcia’s program. With Polytechnic being a predominantly male campus, Garcia said he’s puzzled by the program’s failure to attract minority men, who are the most susceptible to the declining enrollment trend.

“We have these expectations that men cannot complain. Men cannot ask for help,” he said.

One thing that plays a large part in this national phenomenon, Garcia said, is traditional gender roles.

“One of the biggest things is the societal pressure to be a man,” he said. “You have this responsibility and you don’t really have a lot of outlets or resources when you do fail.”

In Arizona, those who do seek help may not get it, as the state lags the country in the number of school counselors available. As of 2018, Arizona’s counselor-to-student ratio was the worst in the nation, at 905 students for every counselor, according to a report from the American School Counselor Association.

ASU students are suffering, as well. An article from the State Press, the campus newspaper, reported monthlong wait times for ASU Counseling Services in November, when students were stressing over finals.

“I’m seeing a lot of folks go straight into the workforce or look at a trade,” Garcia said. “I think there’s a lot of emphasis on making money right now. Why struggle and go into debt for four years when I can get a job right now, making what I’ll make in college?”

College graduates earn an average of $30,000 more than nongraduates, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Osaro Ighodaro, the vice president of student affairs at South Mountain Community College, said 80% of students there are first-generation, meaning they’re the first in their family to go to college.

He said these students lack the male role models to pursue higher education.

“Most of these students come from backgrounds where they don’t even think college is a possibility,” he said.

UArizona, the second largest public university in the state, is witnessing similar trends, although not as drastic as the community colleges are experiencing.

Kasandra Kay Urquidez, the vice president of enrollment management and dean of undergraduate admission, said women are enrollling and graduating at slightly higher levels than men.

“When we look at retention from year to year, our women tend to do a little bit better there,” she said. “I would definitely say that they’re graduating at higher rates, as well.”

One way the schools are trying to counteract this trend is through programs like Opportunities for Youth. The program, which ASU created and is a partnership between several colleges, seeks to engage youth in school and work. It started a few years ago.

Ighodaro said the program has resulted in “steady improvements in attempts of retention” across the community college district.

But the lack of national research could be preventing these programs from reaching their full potential, according to Kishia Brock, the associate vice chancellor at the Maricopa Community College District.

“No extensive research has been conducted – at least from the Department of Education – on why we have seen such a reversal in females essentially dominating higher education,” Brock said. “I think we just really need to dig in … and get a better understanding of what’s fueling this.”