The day after my June 14 graduation from Stanford, my mom pointed to a mud puddle beneath Grandmom’s window.

“It’s fine,” she said. “Put the chair here.”

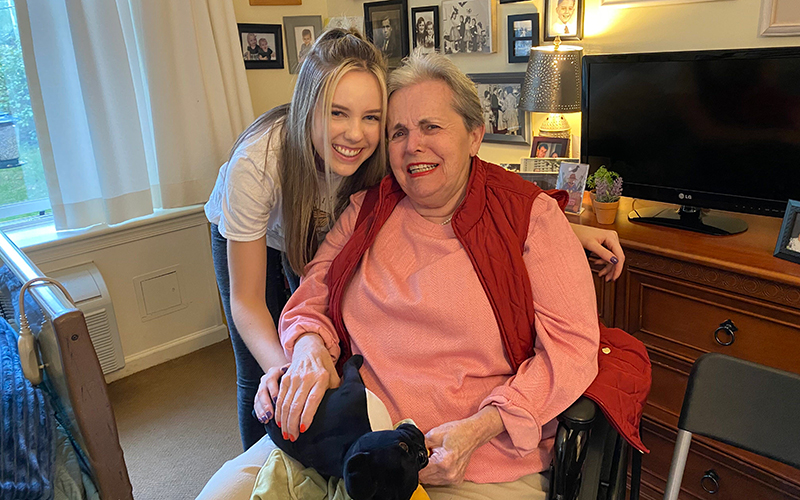

It was the third time we’d visited that week, only this time I was a fresh college graduate dressed in my cap and gown. Scooping up the bottom of the gown, I sat in the folding chair and waved at Grandmom sitting on the corner of her bed. She picked at the quilt, not minding us in the least.

“Mom, it’s Bridget!”

Grandmom looked up, her face contorted like a gargoyle’s.

“Bridget?”

The masked care aide beside her clarified: “Bridget is your daughter.”

Seeming to recognize the word “daughter,” her expression softened into a curious frown.

“Look at Emily in her cap and gown! She just graduated yesterday,” my mom said, pointing at the swinging “2020” tassel.

Her frown was at a tipping point. Just one more joke would do the trick.

“Grandmom, guess what?” I asked, almost putting my nose to the window.

Alarmed, she repeated, “Guess what?”

“I’m getting old!”

All traces of confusion dissipated into laughter. She motioned for us to come inside.

Mom shook her head. “We can’t come inside because there’s a virus.”

The curious frown returned. “A virus?”

“Yeah, there’s a virus, so we can’t come inside.”

Grandmom nodded slowly, mimicking comprehension.

We repeated the entire conversation three more times before storm clouds chased us back to the car.

And so it went for the next several months – COVID-19 cases fell and rose, and clinical trials for a possible vaccine got underway. My mom continued these through-the-window visits with my grandmother. And I started graduate school – virtually, of course – at Arizona State University’s Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

Emily Schmidt stands with her parents, Bridget and Howard Schmidt, in front of their family home after she graduated virtually from Stanford University on June 14, 2020. (Photo courtesy of Emily Schmidt)

The window was where we celebrated milestones with Grandmom – her 78th birthday that September, my mom’s birthday in November, Thanksgiving.

As Christmas approached, COVID-19 cases started surging again. By the third week of December, weekly confirmed cases among nursing home residents peaked at more than 33,000, with 6,000 deaths, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

In past years, Garland and her staff would throw big indoor holiday celebrations, complete with caroling, but that wasn’t an option. So they got creative.

A few days before Christmas, I stood outside my grandmother’s frosted window, the warm breath behind my cloth mask fogging up my glasses. My family surrounded me, singing “Jingle Bells” and clapping gloved hands.

Mom led our terrible choir into the fourth verse of the carol, relying on the packet of sheet music Sunrise provided. Uncle Brian swayed side-to-side trying to keep warm in the 20-degree air. Tara and Dad laughed at Mom’s animated pronunciation of “jingle,” while Aunt Sue and cousin Liz stamped on the snow-covered grass.

Amid the familial choral chaos, I just watched Grandmom. I forgot about my numb fingers and toes seeing her seated on her bed next to three other Reminiscence residents, laughing her laugh and smiling her smile, like she knew Christmas was coming. I almost expected her to break out into “Celtic Alleluia” and waltz around with her friends. But she didn’t. She couldn’t.

When Mom finally concluded her 10-minute rendition of “Jingle Bells,” the most lucid resident clapped her hands like a giddy child opening her first present on Christmas morning.

“What church did you come from?” she asked.

“We’re Pat’s family,” Aunt Sue said.

“Do you want to come inside?”

My mother shook her head. “We can’t because there’s a virus.”

“Did you come from a nearby church?”

“No, we’re Pat’s family.”

“Pat’s family?”

“Yes, Pat Rush.”

The woman turned to Grandmom. “You’re so very lucky, Pat. Your family has come to sing carols for us.”

Grandmom looked at her friend with surprise in her eyes, then glanced back at us, eyes still wide.

“I sure am,” she said, even though most of us felt sure by then that she didn’t know who we were.